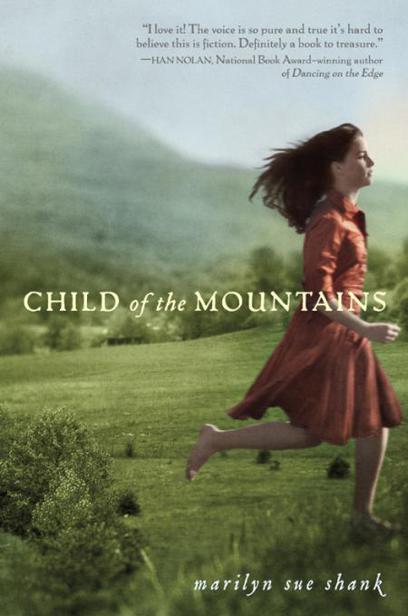

Child of the Mountains

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by Marilyn Sue Shank

Jacket art copyright © 2012 by Richard Tuschman

Map copyright © 2012 by Joe LeMonnier

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools,

visit us at

randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shank, Marilyn Sue.

Child of the mountains/Marilyn Sue Shank.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: In the early 1950s, Lydia Hawkins has grown up poor in the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia with her widowed mother, brother BJ, who has cystic fibrosis, and her Gran, but when Gran and BJ die and her mother is jailed unjustly, Lydia must try to remain strong and clear her mother’s name, even after she learns a shocking secret from the uncle with whom she is sent to live.

eISBN: 978-0-375-98929-2

[1. Secrets—Fiction. 2. Families—Fiction. 3. Self-reliance—Fiction. 4. Christian life—Fiction. 5. Schools—Fiction. 6. West Virginia—History—1951—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.S548413 Ch 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2011026174

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To my brother, Tom Shank

,

and in loving memory of my father, Joe Shank

,

and my mother, Lenah Shank—proud West Virginians

who gave me reason to value my heritage

.

And to all children of the mountains: “Rise and shine!”

These women of Appalachia, they didn’t survive.

They prevailed.

—

Margaret Hatfield

from the West Virginia History Film Project

It’s about my problem

It’s about my problem.

W

EDNESDAY

, O

CTOBER 28, 1953

My mama’s in jail. It ain’t right. Leastwise, I don’t think so. Them folks that put her there just don’t understand our family. My mama’s the best mama in the whole wide world. Everbody used to say so afore the awful stuff happened. Even Uncle William. And he don’t say much nice about nobody.

I got to get her out. But how? Even when they’s wrong, once grown-ups make up their minds about something, a kid like me don’t stand much of a chance of changing it. Poor Mama. I know she hates being caged up like a rabbit, and it’s all my fault.

I feel like my heart done shattered in tiny pieces, like Gran’s vase that me and BJ broke playing tag one time.

And I ain’t got nobody to help me put them pieces back together.

That’s why I stopped by the company store after school yesterday and bought me the biggest spiral notebook they had. Maybe writing everthing down will help me sort it all out.

“Lydia, when you came to be, you was my only star in a dark, dark sky,” Mama always said. When I lived in Paradise, Mama and Gran always made me and BJ both feel like we was right special to them.

But sometimes a body can feel all alone, even when other people live in the same house. That’s how I feel living with Uncle William and Aunt Ethel Mae here in Confidence, West Virginia. They be nice enough people, but they ain’t got nary a clue about what to do with me.

The bad stuff commenced like this: My brother, BJ, was borned awful sick, but we didn’t know it at first. When Mama birthed me, Gran said I didn’t cause Mama no trouble at all. Daddy was at work, so Gran hollered to a neighbor across the road that I was a-coming soon. The neighbor got in his car and went to fetch old Doc Smythson.

When Doc Smythson comed to help Mama, Gran told him she could manage things just fine, but he said he would be awful obliged iffen she let him help because it was his doctoring duty. So Gran figured it would be okay. But Gran told me that she really done most of the work, after Mama, of course. Gran midwifed most of the women

around these parts. She fixed Mama blue cohosh tea to sip and tickled her nose with a feather.

Gran said, “When your mama sneezed, you whizzed out of her like a pellet from a shotgun. All Doc Smythson had to do was hold out his hands to catch you.” Gran shook her head. “Ain’t like you have to go to some fancy school to learn how to do that!”

But things sure turned out different with BJ. I recollect the whole thing. I was four years old at the time. Gramps and Daddy lived in Heaven by then. Me and Mama and Gran lived in Gramps’ cabin all by ourselves.

When BJ was about to come, Mama started bleeding real bad, and she screamed like a hound dog a-howling at the moon. Nothing Gran mixed from her herb bottles helped none. Gran sent me running to the neighbors’ house to have them find Doc Smythson.

Doc took one look at Mama and told Gran he had to fetch her to the hospital in Charleston straight away. But we didn’t have no ambulance close by where we lived. Sometimes the men from the funeral home took folks to the hospital in their hearse. But they couldn’t get to our house soon enough for my mama, tucked way back up in the mountains as we are.

So Gran wrapped Mama up in blankets, and Doc carried her like a sack of taters to his jeep. Her eyes was closed like she was asleep. I cried out to her, “Take me with you, Mama! Take me with you!”

She opened her eyes just a little and looked at me. Her

lips said, “I love you,” but no sound come out at all. Doc sped off with her to the big hospital in Charleston.

Tears commenced to roll down my cheeks when I watched them drive away. Gran smoothed the hair back from my face with her hands, rough as a cat’s tongue. “Your mama needs us to stay here and look after things for her, pumpkin,” she said.

When me and Gran went back inside, Gran pulled Mama’s bloody sheets offen the bed and took them to the washtub. I couldn’t bear to watch the water take Mama’s blood away, thinking that was all I had left of her. So I runned under the kitchen table and curled up like a woolly worm that somebody poked with a stick.

After Gran got done a-scrubbing and a-hanging out the sheets to dry, she leaned under the table and took my hand. “Come on, child,” she said. “Your mama needs us to be strong for her. Besides, I ain’t got the bones for bending down like this. You ain’t helping your mama none by hiding under the table. Let’s fix up the cabin all nice for her and the baby to come home to.” I crawled out, and Gran handed me a little broom Daddy made for me afore he died.

I got myself busy sweeping the floors ever day Mama stayed at the hospital. Gran said, “Lydia, I declare, you’re going to wear holes in the floor clean through to Chiny iffen you keep that up.” But I wanted them floors to be spanking clean for my mama.

Mama finally comed back and brought my new baby brother with her. Gran folded up a blanket and laid it in a

dresser drawer on Mama’s bed for him to sleep in. It made me think of Baby Jesus in the manger to see him lying there all cozied up.

Mama named my brother Benjamin for my grandpa on Daddy’s side and James for my gramps on Mama’s side. But he looked just too little to be Benjamin James. I wanted to call him Ben Jim, but Gran said, “Mercy, pumpkin, that sounds more like the name of a tonic than a fitting name for a boy. I can hear it on the radio now. ‘Ben Jim heals your soul and heart, mends your body and makes you smart, keeps you strong and cures the farts.’ ”

So we took to calling him BJ instead.

BJ looked as cute as a speckled steamboat on a spotted river, as Gran used to say, even iffen he was as skinny as a straight pin. He had big blue eyes the color of our pond when it froze over. Them eyes looked clean through you, right inside to your very soul. His hair was the color of a ripe ear of corn. I used to hold him on my lap and tell him stories—about our daddy, about living up here on the mountain, and about how much we all loved him. He’d look at me and grin, and this little dimple would creep up like an extra smile.