Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society (29 page)

Read Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society Online

Authors: Adeline Yen Mah

A voice behind me said, ‘What are you thinking?’

I turned and saw David, Sam and Marat. I wondered who had spoken. Then David said, ‘I know it’s terrible to lose your Big Aunt, but remember you will never be alone again. You are our Little Sister, a fellow member of our Dragon Society of Wandering Knights. Besides, we need you for our future missions. This is just the beginning.’

‘I was wondering what to do about my father.’

There was a short silence, then Sam said, ‘Maybe this will help you. It’s from a book of Jewish writing called the

Zohar.

“Honour your father and mother, even as you honour God, for all three were partners in your creation.” ’

‘Why don’t you telephone your dad when you

get to Chungking?’ Marat said. ‘You’ll be safe from the Japanese there. He must be worried about you. We hate to see you sad like this. Now that we are fellow members, your pain has become our pain.’

I thought of phoning my father. But the image that came to mind was my meeting him at the front door of our house when Ah Yee brought me home from the academy. How awkward and tongue-tied we both were. There had been so much I wanted to say… but the mood and circumstances were all wrong. And in the end I had said nothing at all.

No. I needed to communicate with him in a different way. It should happen on an auspicious day of my choosing: a special day dedicated solely to telling him what I longed to express. I would wait for the right moment and place, and search for the necessary words to convey all that was buried within my heart. Hopefully, if I was very lucky, I’d be able to give him my truest explanation… and he would understand.

‘Because of your friendship and advice,’ I said. ‘I now know what I must do. When we get to Chungking, I’m going to write my father a letter. In it, I’ll tell him about Big Aunt’s murder, and everything I’ve been unable to say since Niang came into our lives. I’ll also try to put in my

heart and spirit. Perhaps such a letter will bring him consolation and solace… and me too, in the writing of it.’

Sam nodded and took out from his pocket his piece of yellow silk. The four of us held hands and chanted in one voice, ‘We are in China at this moment in history for a reason. We are here to make a difference. We are children of destiny who will unite East and West and change the world. The future belongs to us!’

Historical Note

Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society

is a fantasy based on a true incident that took place in China during the Second World War. To understand the story’s historical background, we need to go back to the first half of the nineteenth century.

My grandfather Ye Ye ( ) was born in Shanghai in the year 1878. He told me that his father, my great-grandfather, was born in 1842, the same year that China lost a war against Britain known as the Opium War. As a result of the peace treaty, five port-cities along China’s coast were placed under foreign rule. In treaty-ports such as Shanghai in the 1940s, we Chinese lived as second-class citizens under the British, French, American, Japanese and other ‘conquerors’.

) was born in Shanghai in the year 1878. He told me that his father, my great-grandfather, was born in 1842, the same year that China lost a war against Britain known as the Opium War. As a result of the peace treaty, five port-cities along China’s coast were placed under foreign rule. In treaty-ports such as Shanghai in the 1940s, we Chinese lived as second-class citizens under the British, French, American, Japanese and other ‘conquerors’.

The best areas of Shanghai were turned into foreign settlements (also called Concessions), which

were governed by foreign consuls according to foreign law. Disputes were judged according to British law in the British Settlement (also named the International Settlement) and French law in the French Concession.

In 1911, when my Ye Ye was thirty-three years old, China underwent a revolution and the imperial Manchu court in Beijing (Peking) was overthrown. Sun Yat-sen became president and proclaimed China a republic. After Sun’s death in 1925, General Chiang Kai-shek became China’s leader.

Despite the change of government, China remained weak. Meanwhile, Japan was pursuing a policy of military expansion. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria in north-east China. Six years later, in July 1937, Japan declared war on China. For the next four years, Japan took control of China’s coast but did not invade the foreign Concessions. Chiang Kai-shek fled up the Yangtze River and moved his capital to Chungking, a city 800 miles west of Shanghai.

On 7 December 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in Honolulu and declared war on the US and Great Britain. A few hours later, Japanese soldiers marched into Shanghai’s International Settlement, eventually interning all British and American residents. Since France had fallen to

Japan’s ally Germany one year earlier and Shanghai’s French Concession was under the administration of Vichy France, the Japanese did not intern the French.

To govern China’s occupied territories, Japan set up a puppet regime headed by Wang Ching-wei. However, many of Wang’s Chinese troops resented the Japanese and secretly sided either with Chiang Kai-shek or the Chinese Communists.

My father bought a house in the French Concession of Shanghai in 1942 and spent the next six years there. I went to a French convent school two miles from home and walked to and from school every day. Many of the scenes described in this book were culled from my memory.

On 18 April 1942, sixteen US bombers under Jimmy Doolittle took off from the aircraft carrier USS

Hornet

and bombed four Japanese cities. None was shot down.

The Ruptured Duck

and another plane crashed into the sea near the island of Nan Tian. All ten crew members survived the crash, but the pilot of

The Ruptured Duck,

Ted Lawson, had to have his leg amputated.

Other crewmen were not so lucky. Eight men from two other US planes were captured by the Japanese after their planes crashed in Japanese-controlled territory.

After the raid, the Doolittle raiders, as they were

known, became famous throughout the world. For the first time in the history of Japan, the sacred motherland had been violated and bombed by the enemy. In their fury and humiliation, the Japanese unleashed a savage attack on the defenceless Chinese people for helping the airmen.

The bloodbath began on 15 May 1942 and went on for three months. To seek revenge, 148,000 Japanese troops were sent into Zhejiang Province. Countless numbers of Chinese were killed when Japanese planes dropped anthrax spores as well as fleas infected with bubonic plague on the hapless populace. Many who died had never even heard of the Doolittle raid.

‘When the Japanese finally withdrew in August 1942,’ the historian David Bergamini wrote in his book

Japan’s Imperial Conspiracy,

‘they had killed 250,000 Chinese, most of them civilians. The villages at which the American fliers had been entertained were reduced to cinder heaps, every man, woman and babe in them put to the sword. In the whole of Japan’s eight-year war with China, the vengeance on Zhejiang Province would go down unrivalled…’

An outraged Chiang Kai-shek sent the following cable to the US State Department in 1942: ‘After they had been caught unawares by the falling of American bombs on Tokyo, Japanese troops

attacked the coastal areas of China where many of the American fliers had landed. These Japanese troops slaughtered every man, woman and child in these areas – let me repeat – these Japanese troops slaughtered every man, woman and child in these areas, reproducing on a wholesale scale the horrors which the world had seen at Lidice

*

but about which the people have been uniformed in these instances.’

This book is a fantasy and describes the rescue of the crew of

The Ruptured Duck

from Nan Tian Island by four children who were members of a secret resistance society. The children also engineer a break-out of four captured US airmen from Bridge House, an infamous Japanese prison and torture chamber. Although these children are characters from my imagination and never existed in real life, their backgrounds are historically accurate. Children of mixed race were called

za zhong

( ) and were very much despised in Shanghai during the 1940s.

) and were very much despised in Shanghai during the 1940s.

The real names of the US airmen were used in

this book. However, in order to maintain the flow of the narrative, I took certain liberties with the time frame as well as ages and the eventual fate of the captives.

In actuality none of the US crewmen escaped from prison. After their capture, they were first taken to Tokyo before being sent back to China and incarcerated in Bridge House. One died of malnutrition in prison and three were executed as described. The letters quoted in the chapter tided ‘Last Letters’ are authentic and came from the pens of Dean Hallmark, Bill Farrow and Harold Spatz just before they died.

In August 1945, Japan lost the war and surrendered unconditionally to the allies. The four captured US crewmen who survived their imprisonment were released. One of the four, Jake DeShazer, became a missionary and returned to Japan where he spent thirty years of his life (1948-78).

Chinese Cinderella and the Secret Dragon Society

is an attempt on the part of one Chinese-American writer to inform the world of the horrors of war.

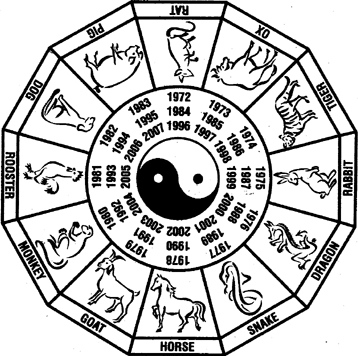

The Chinese Zodiac

Legend has it the twelve animals of the Chinese Zodiac were chosen by Buddha. Adeline explains all about it in Chapter Two of this book. The Chinese New Year is between late January and

early February and this is when the next animal year starts.

One polite way of finding out someone’s age in China is to ask that person, ‘Under which animal sign were you born?’ If she says, ‘Ox,’ you’ll know that she was born in either 1985 or 1997. If she says, ‘Rat,’ you’ll know that she was born in 1984 or 1996… and so on. Find the year of your birth on the chart to discover which animal sign you are, and some of your characteristics!

The Year of the Rat (1900, 1912, 1924, 1936, 1948, 1960, 1972, 1984, 1996, 2008)

You are imaginative, charming and generous. You have big ambitions, work hard to achieve your goals and are a perfectionist. You tend to be quick-tempered and can be critical of others. You get along well with Dragons, Monkeys and Oxen.

The Year of the Ox (1901, 1913, 1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, 2009)

You are a born leader and inspire confidence in others. You are methodical and skilled with your hands. Although generally easy-going, you can be

stubborn and hot-tempered. You are most compatible with Snakes, Roosters and Rats.

The Year of the Tiger (1902, 1914, 1926, 1938, 1950, 1962, 1974, 1986, 1998, 2010)

You are sensitive, emotional and loving. You are a deep-thinker, carefree and courageous. But you can be short-tempered and often come into conflict with people in authority. You find it hard to make your mind up and then make hasty decisions. You get along well with Horses, Dragons and Dogs.

The Year of the Rabbit (1903, 1915, 1927, 1939, 1951, 1963, 1975, 1987, 1999, 2011)

You are talented and affectionate, and admired and trusted by others. You like to gossip, but are nonetheless tactful and kind. You are wise and even-tempered, and tend not to take risks. You are compatible with Goats, Pigs and Dogs.

The Year of the Dragon (1904, 1916, 1928, 1940, 1952, 1964, 1976, 1988, 2000, 2012)

You are energetic, popular and fun-loving. You are also honest, sensitive and brave. You appear

stubborn, but are soft-hearted and sensitive on the inside. You are compatible with Rats, Snakes, Monkeys and Roosters.