Chinese Healing Exercises (31 page)

Read Chinese Healing Exercises Online

Authors: Steven Cardoza

Tags: #Taiji, #Qi Gong, #Daoist yoga, #Chinese Healing, #Health, #medicine, #remedy, #energy

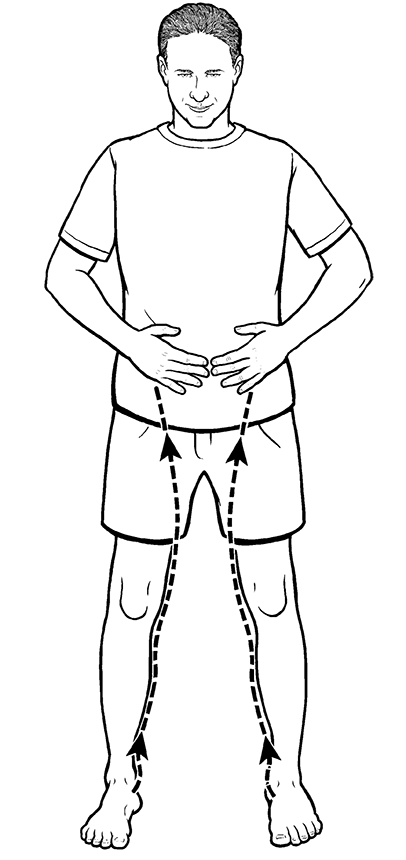

Figure 11.3D (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

Figure 11.3D (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

4. Qi Storage at the Dantian

The Dantian is one of the main energy centers in the body. Although there are three primary Dantiansâupper, middle, and lowerâwhen the word

Dantian

is used alone without any stipulation, it's almost always the lower Dantian being referred to. That's because the lower Dantian has the most to do with physical functions, health, and vitality, so it has most to do with everyday life and with the interests of the majority of people involved in energy practices. It also serves as the main reservoir of the energy acquired through various qi practices, so learning to store qi at the Dantian is the main, if not only, way to have a net gain of energy at the end of the day.

If you practice taiji or qigong, you may have generated more qi or drawn healthy qi in from your environment. If you've practiced a self-care exercise set, you have freed up some previously unusable qi within your body. In either case, it's a good idea to store what is now a surplus of qi, so that it does not simply dissipate over the course of the day. There are many ways to store qi. This is one of the simplest, and is best done after Running the Meridians or Dragon Playing with a Pearl.

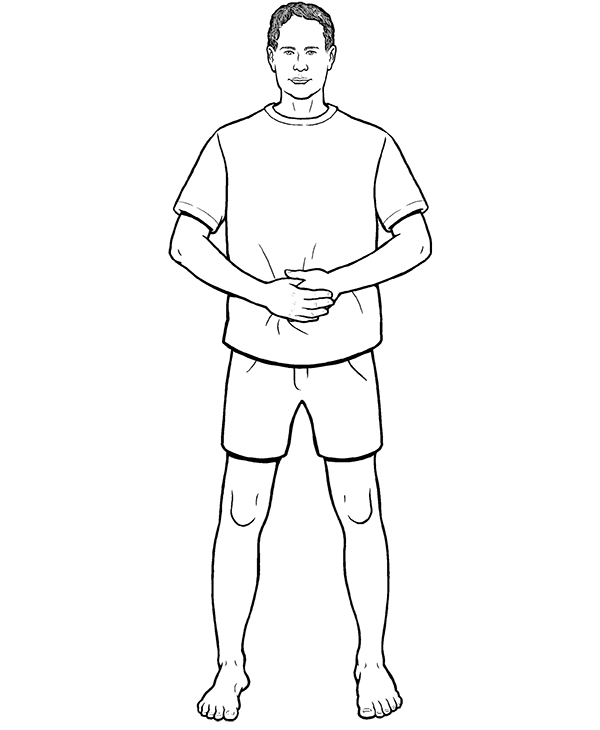

After the twelfth repetition of running the leg meridians, your hands naturally arrive at your lower belly, where your Dantian is located. This time, do not slide your hands around your waist to the small of your back, but leave them at your low belly, just below your navel. Men should place their left hand directly on their belly and cover it with their right hand

(

Fig 11.4

on next page

),

while women should place their right hand directly on their belly and cover it with their left hand. This is because in men, the right hand is the more Yang hand, and in women the left hand is the more Yang hand. Yang is naturally protective and stays more to the surface relative to Yin, and Yin is nurturing and stays more interior relative to Yang. This hand placement simply follows the natural order of Yin and Yang.

Figure 11.4 (Qi Storage at the Dantian)

Figure 11.4 (Qi Storage at the Dantian)

After running the meridians, your hands should still feel slightly warm. You can use that warmth as a tactile reference. With your hands placed just below your navel, allow the warmth to penetrate your low belly, all the way to your Dantian, two to three inches in from the surface of your body. For most people, it will be easiest to close the eyes to avoid any external distraction, and use the mind to feel for that warmth at the Dantian. If you don't feel the warmth, that's okay, because the warmth is not the qi itself; it's just a guide to help you feel it. Allow your mind to settle on that location as best you can. You may experience any of a variety of other sensations there: motion like wind or water, tingling, tickling, or a sense of light or expansiveness. Again, you may feel none of those things and that's okay too. If you do feel something there, simply keep your mind on it until it quiets and stops. Whether you feel anything specific or not, if you keep your mind on your Dantian, qi will be stored there. At some point you will feel a sense of peace, stillness, or completion, and then you've finished storing what qi you can for the day. It may take just a few seconds or a few minutes. When you feel you are through, lower your hands to your sides, open your eyes, and move on to whatever is next in your day.

5. Follow Your Breath Meditation

Every previous practice in this book has directly addressed some aspect of the physical body. Some of those have enlisted the mind toward that end. This meditation practice is included now specifically to benefit the mind. Since every physical process is under the direct regulation of the mind and the organ it is most obviously associated with, the brain, the entire body will benefit from meditation practice.

The brain is the central processing unit of the nervous system, relying on, controlling, and responsible for all the electrical activity in the body. When the brain and nervous system are overdriven, stress is the inevitable result, setting the stage for all the diseases caused by stress, and most of the chronic aches and pains anywhere in the body. When the brain

is quieted, mediated by the mind, that electrical activity diminishes, tension discharges,

stress drops away, and the stress-induced disease processes and pain can be halted and reversed. The mind also plays a role in emotional responses and experiences, and emotions influence and are influenced by neurotransmitters and other hormones. It is well known to Chinese medicine that lingering emotional states always affect health (usually adversely), and conversely, imbalances in the function of each organ and organ system create a unique emotional proclivity. A calm, balanced, quiet mind reduces and ultimately eliminates emotional upset. The external circumstances may not change, but your response to those circumstances can and will change. This is how the hormonal systems can benefit and not become overtaxed, and another way the nervous system is benefited.

There are many types of meditation. Most are intended to turn off the conventional thinking processes, quiet the mind, and create an inner stillness that allows for a nonintellectual awareness, a sense of simply being, and the perception of a connection with everything in existence. The sense of just being, existing in the moment, removes any worry and anxiety stemming from concerns about the future and regrets of the past. The perception of connection with all things in existence gives a sense of belonging, acceptance, grounding, and certainty about one's place in the world.

There may be no other time in history when meditation practice has been more necessary than it is today. With so many people completely “plugged in” to modern technologyâwith cell phones, texting, instant messaging, constantly working or playing on a laptop or iPad, updating Facebook status, Tweeting, having both jobs and families that demand you are electronically if not physically accessible twenty-four hours a day, and streaming audio and video news and entertainment to a computer or TV much of the rest of the timeâeveryone is perpetually distracted outside of themselves, seldom given the opportunity to catch their breath and learn more about who they really are, away from all those distractions. Paradoxically, most people also consider these contemporary distractions to be “normal life,” and the thought of being without them may seem both impossible and boring. In fact, the perception of boredom has always been one of the biggest obstacles people have faced when beginning a meditation practice, and even when beginning some of the slower-moving or stationary practices of qigong, taiji, and gongfu. If you are one of those people, this may interest you and help you overcome your reservations.

Even outside of the context of meditation, new scientific research has demonstrated that enforced boredomâbeing made to do a mindlessly repetitive taskâand relaxed boredomâdaydreamingâserve a creatively useful purpose. In his book

Boredom: A Lively History

(Yale Press), University of Calgary professor Peter Toohey, PhD, cites studies at the University of British Columbia which showed that in volunteer students given mindless, routine assignments while having their brains scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging, there was a high amount of activity in the part of the brain associated with complex problem solving. This indicates that when your mind is free of external distractions, it can work on puzzles, problems, and more abstract concepts, helping you find solutions that might otherwise elude your conscious thought processes. This has long been acknowledged as one of the side benefits of meditation, and is a likely mechanism to explain some aspects of inspiration and creative thought.

This entry-level meditation is very simple, yet very effective. Some variation of this practice is used in almost every spiritual and secular meditation tradition throughout the world.

Method

Sit on a hard or firmly cushioned chair, nothing too soft, at a height that allows your knees to be bent at about a 90-degree angle. As long as your back is not in pain and in need of support, sit on the forward third of the seat. Do not lean back on the chair back, and do not slouch. Sit erect and upright, but without strain or force. Even though you are seated, keep your feet parallel at about shoulder width apart with your knees aligned directly above your feet. You can place your hands on your knees, or fold them in your lap. If you are not already an experienced meditator, hands placed on your knees will extend your arms and help to keep your armpits open, allowing for a freer flow of qi between your arms and torso. Place the tip of your tongue at the roof of your mouth, just behind where your teeth meet your gums. This connects two major energy pathways in the body, the Du meridian running up your back, over your head and ending at the roof of your mouth, and the Ren meridian running up the centerline of the front of your body and ending at the tip of your tongue. This posture will keep your body most open, create energetic connections, and allow for qi to move freely with minimal physical obstructions while you meditate.

Next, pay attention to your breathing. Breathe in and out only through your nose, unless you have a nasal obstruction that makes that impossible. Your breath should be comfortably long, and will likely get longer as you practice over time. Your breath should also be silent and slow, not coarse, noisy, or rough. Most people have a natural stopping point at the end of their inhalation and exhalation, where they have a pause, a brief period of held breath. Try to keep your breath continuous, so there is no pause between inhalation and exhalation. That creates a sense of circularity in your breathing rhythm. Still sitting erect, keep your belly soft and relaxed. Do your best to keep your chest still and sunken, so that it does not rise or expand forward when you inhale, nor drop when you exhale. With your mind, feel the region between your lowest ribs and your pelvis. On your inhalation, direct your breath to that region, and let it expand in all directions, including toward your back, like a balloon filling with air. On your exhalation, allow everything in that region to retract toward the center of your body, as though air was being released from the balloon. Practice this for a few minutes, with your eyes open or closed; either is fine. Most people find that closed eyes help remove external distractions and facilitate sensitivity to inner processes. The better you are able to breathe in this way, the more tension will be released from your nervous system, and the more deeply you will relax when you meditate.

The final piece of this practice begins the actual meditation. It's called “following your breath” because that's exactly what you're going to do, in one of three ways. Each way gets slightly more challenging and takes you a little further, but all yield good results. In the first way, each time you inhale, silently say to yourself, “inhale,” and each time you exhale, silently say to yourself, “exhale.” Let that be the only thought in your mind. It's inevitable that other thoughts will arise, but when you notice them don't try to force them away; simply bring your attention back to “inhale, exhale.” The second way requires you to extend your focus just a bit farther than “inhale, exhale.” On every exhalation, count the number of your breath, so that on your third exhale for example, you will silently say “three” to yourself, on the seventh exhale, you will say “seven,” and so on up to ten. Then begin counting again from one. Repeat this counting as long as you'd like. The third way is similar to the second, but you do not stop the count at ten and start over; instead, you continue counting each breath in order until you end your meditation. The numbers continue to increase the longer you meditate. Your focus will need to extend farther in this practice, as you will need to keep track of your count throughout the meditation. As with the “inhale, exhale” variation, when extraneous thoughts arise, don't try to force them awayâsimply notice and release them, and bring your attention back to your count.