Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World's Greatest Chocolate Makers (33 page)

Read Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World's Greatest Chocolate Makers Online

Authors: Deborah Cadbury

Tags: #Food

Swimming lessons for staff at Bournville, 1910. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

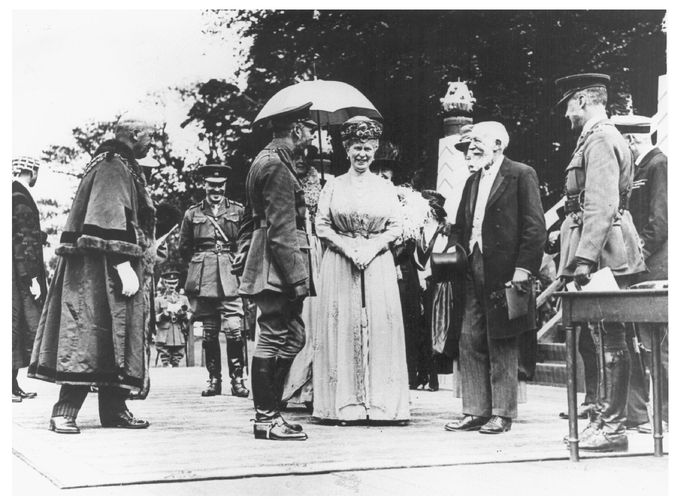

King George greeted by George Cadbury, 1919. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

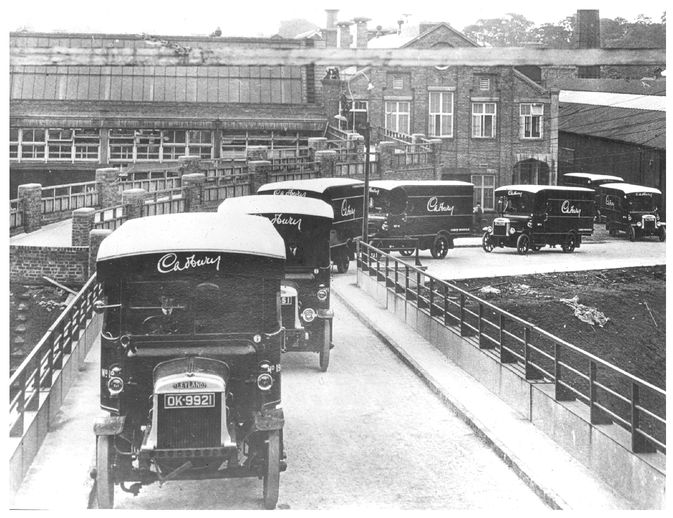

Vans leaving the factory. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

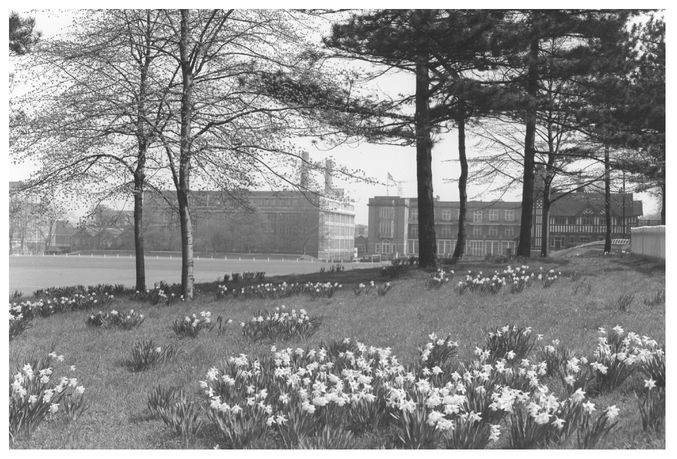

Bournville: the factory in the garden. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

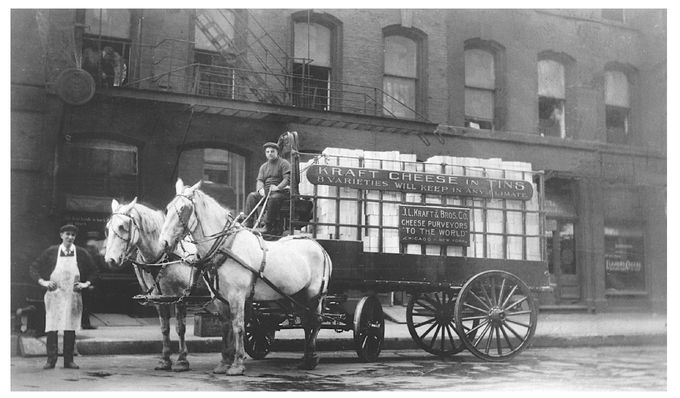

Kraft cheesewagon, 1921.

(KRAFT®, PHILADELPHIA®, VELVEETA® AND MIRACLE WHIP® ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF KF HOLDINGS AND ARE USED WITH PERMISSION.)

By 1939, J. L. Kraft had 40 percent of America’s cheese market.

(KRAFT®, PHILADELPHIA®, VELVEETA® AND MIRACLE WHIP® ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF KF HOLDINGS AND ARE USED WITH PERMISSION.)

Milton and his wife, Catherine “Kitty” Hershey, 1910.

(COURTESY OF HERSHEY COMMUNITY ARCHIVES, HERSHEY, PA)

Milton Hershey used his fortune to create The Hershey Industrial School to help boys from deprived backgrounds.

(COURTESY OF HERSHEY COMMUNITY ARCHIVES, HERSHEY, PA)

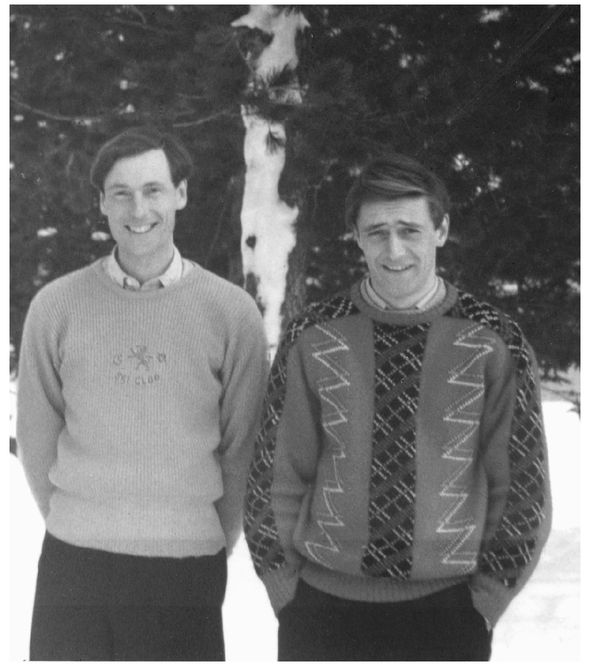

Adrian and Dominic Cadbury, the fourth generation of brothers at the helm of the firm. (COURTESY OF THE CADBURY FAMILY)

The Nestlé company kept a close eye on the deal. No sooner had Kohler and Peter completed their negotiations when they received a call from Auguste Roussy at Nestlé. Roussy had originally declined to help Peter develop his milk chocolate. Now Nestlé was hungry to get into the lucrative milk chocolate market and had plans to launch brands of its own.

During the long summer of 1904, talks took place between Peter and Kohler and managers at Nestlé. The result was a collaboration that favored both sides. Nestlé invested a million Swiss francs with Peter and Kohler and agreed to hand over the manufacture of Nestlé’s own brands of chocolate to them. In return Société Générale Suisse de Chocolat was given access to Nestlé’s excess milk supplies and the company’s considerable expertise in sales and marketing and established position in foreign markets. Effectively the agreement meant that each company specialized in what it did best: Nestlé handled chocolate distribution and sales while Peter and Kohler concentrated on quality manufacturing.

But when Nestlé’s deal with Peter and Kohler was announced, Nestlé’s main rival, the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company was spurred into action. Founded by two Americans, Charles and George Page, Anglo-Swiss had been Nestlé’s leading competitor for thirty years, and it also wanted to get in on the chocolate bonanza. When it failed to secure a deal with other Swiss chocolate firms, such as Suchard, it approached Nestlé. In 1905 the two companies merged to create a Swiss dynamo. The Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company was a truly international food concern with American and European staff and expertise and eighteen factories worldwide, including five in Britain, twelve in Europe, and one in America.

By skillfully combining their assets and talents, the Swiss had launched a food manufacturing superpower, which could already deliver milk chocolate to Europe and America and had plans to tap into Australia and Asia as well. While the Americans and the British had only recently discovered their recipes, the Swiss deals meant

that consumers throughout the developed world would soon wake up to the delights of quality Swiss milk chocolate.

that consumers throughout the developed world would soon wake up to the delights of quality Swiss milk chocolate.

But even the sophisticated Swiss bankers, with their eyes fixed on the American market, had not bargained on the well-honed entrepreneurial skills of Milton Hershey. By 1906 the town of Hershey was on the map. On entering, the visitor was left in no doubt of that fact. The name proclaimed itself with confidence, writ large and bold and frequently. It shone from the towering factory chimneys and blazed above the main factory entrance, reminding anyone who passed through that determination over an indifferent fate by Milton Hershey had created a living fairy tale: A town that made chocolate.

The sheer scale of his operation in America dwarfed the efforts by the Europeans. Apart from his milk chocolate Hershey Bar, he introduced conical chocolate drops called Hershey’s Kisses in 1907, followed swiftly by Hershey’s Almond Bar. With his leading rivals an ocean away and the voracious American appetite spreading from coast to coast, he had created a chocolate money machine. Net sales soared from $1.3 million in 1906 to more than $5 million by 1911.

Thousands of visitors flocked to see Hershey’s miracle and to marvel at the astounding chocolate factory. The factory in a cornfield was not unlike Bournville but it was done on an American scale. Sightseers could enjoy a stroll down the wide boulevards and wander into the center of town, which boasted such novelties as landscaped gardens, a zoo, a miniature railroad, and a band. Shops sprang up along the main avenues, and there were carefully designed homes for the workers to buy or rent. All the while, Hershey continued to buy up thousands of acres near the town, which he turned into dairy farms to supply the factory. The entire region prospered.

At the very heart of this chocolate utopia was Hershey’s palatial home, High Point. Approached across a green carpet of lawn, its

many wings framed by woodland and a view of the Blue Mountains beyond, it was the embodiment of material success. With its white-pillared porch reminiscent of ancient temples, fine interiors, and echoing halls, the house was so opulent that it could not have been further from the plain homestead of Milton’s youth. Hershey’s mother, a Mennonite, gave her full approval to her successful son. She had her own large house on Chocolate Avenue, and her financial troubles were over. Known as “Mother Hershey” or sometimes “the Queen mum,” she enjoyed a respect in the community that she prized after many long years of struggle. Not content to wallow in her newfound comfort, she combed her grey hair into a starched cap, donned her apron, and continued to wrap sweets for her son as she had always done. Their new wealth and the company’s potential seemed limitless.

many wings framed by woodland and a view of the Blue Mountains beyond, it was the embodiment of material success. With its white-pillared porch reminiscent of ancient temples, fine interiors, and echoing halls, the house was so opulent that it could not have been further from the plain homestead of Milton’s youth. Hershey’s mother, a Mennonite, gave her full approval to her successful son. She had her own large house on Chocolate Avenue, and her financial troubles were over. Known as “Mother Hershey” or sometimes “the Queen mum,” she enjoyed a respect in the community that she prized after many long years of struggle. Not content to wallow in her newfound comfort, she combed her grey hair into a starched cap, donned her apron, and continued to wrap sweets for her son as she had always done. Their new wealth and the company’s potential seemed limitless.

Other books

Life With Toddlers by Michelle Smith Ms Slp, Dr. Rita Chandler

Queens' Play by Dorothy Dunnett

Pieces in Chance by Juli Valenti

La Navidad para un niño en Gales by Dylan Thomas

Missing by Noelle Adams

Belonging to Bandera by Tina Leonard

Almost Dead (Dead, #1) by Rogers, Rebecca A.

Vampire "Unseen" (Vampire "Untitled" Trilogy Book 2) by Lee McGeorge

Mrs. Kimble by Jennifer Haigh

The Lovely Reckless by Kami Garcia