Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (19 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

By the 1880s, Chinese workers had helped build thousands of miles of railroads. The American West was now linked to the rest of the country by four main railroad lines, and smaller railways connected many western communities and mining areas. Many of the laborers settled in towns along the tracks, like Tucson and El Paso, where they found work in farming or by opening stores, laundries, and restaurants. Cheap cafés owned by Chinese had been around since the 1850s in California, so it was not a surprise when these eateries sprang up. The waiters or waitresses were often white (or Mexican American in some locations), while the Chinese cook-owner stayed back in the kitchen. The menu was strictly inexpensive American fare—steak and eggs, beans and coffee, though a Chinese customer could probably get a bowl of rice or noodle soup if he stepped back into the kitchen. The local whites along the railroad lines weren’t yet ready to convert to Chinese food.

From railroad dining rooms to the chuck wagons that followed cattle drives, Chinese cooks helped feed the American West. During the 1870s, the Central Pacific dining room in Evanston, Wyoming, featured Chinese waiters in native costume serving “excellent” western food prepared by Chinese hands in the kitchen. As in Gold Rush–era San Francisco, Chinese cooks in the remote mining districts learned to prepare American staples just like the natives. At the Polyglot House store and restaurant in Hangville, California, the kitchen churned out dishes that were more fuel than food: “pork, badly baked bread, and beef hardened but not cooked in hot grease,” imitating “the American style with a painful accuracy.”

46

If the diners didn’t like the food, they would often beat the cook. After his work was done, the cook would retire to the Chinese camp nearby, where he would enjoy more civilized fare and company. During the Black Hills Gold Rush of the 1890s, Deadwood, South Dakota, boasted seven Chinese-owned eateries with names like the Philadelphia Café, the Sacramento Restaurant, the Lincoln Restaurant, and the Chicago Restaurant. Although the owners kept bottles of rice wine for their customers to sample, the menu was strictly inexpensive American—T-bone steak and apple pie. Deadwood was a rare western community that was relatively accepting of Chinese, so the owners didn’t have to keep to the kitchen and hire white waiters or waitresses to tend to diners. During the great cattle drives of the 1870s and 1880s, Chinese chuck wagon cooks prepared the biscuits, beans, coffee, and bacon that fueled the cowboys. Like all Chinese in the West, the camp cook lived with the possibility that whites could turn against him at any time. Generations later, the 1930s song “Hold That Critter Down” (written by Bob Nolan) described torturing the cook as part of roundup fun:

When the sun goes down and the moon comes ‘round

To the old cook shack we’re headin.’

We’ll throw the pie in the Chink cook’s eye

And tie him up in his beddin.’

And make him run to the tune of a gun

So hold that critter down. . . .

After the Civil War, the anti-Chinese racism that had long simmered in the West came to a boil. The migrants who now streamed into California, many of them from Ireland, discovered that most of the jobs on the major construction projects—the railroads—were reserved for Chinese. These white migrants formed “anti-Coolie” leagues and trade unions that made expulsion of all Chinese people from the West one of their prime goals. Politicians discovered that promoting the cause that “the Chinese must go!” could win elections. Newspapers jumped on the bandwagon, reprinting Bayard Taylor’s most incendiary writings and fanning the flames in order to sell more papers. Local governments passed a number of discriminatory laws designed to make the lives of California’s Chinese more difficult. The Chinese could not vote, but they did fight back with lawsuits and diplomatic initiatives, which were only partially successful. In October 1871, during a gunfight between two Chinese gangs in the street nicknamed “Nigger Alley,” the heart of Chinatown in Los Angeles, a white man was killed in the crossfire. In retaliation, a mob of a thousand white men armed with “pistols, guns, knives, ropes” stormed the quarter and killed over twenty Chinese people. Eight men were eventually found guilty of the murders, but their convictions were overturned. This massacre caused widespread revulsion, but that wasn’t enough to stop the anti-Chinese movement, particularly after a financial panic caused record unemployment in California.

Just in time for the 1876 elections, the issue of Chinese expulsion caught the ear of Washington, and a special joint congressional committee was sent to San Francisco to investigate the situation. The congressmen queried a succession of local white “experts,” but no Chinese, on such topics as Chinese crime, morality, sanitation, disease, economic competition, and refusal to assimilate, and on “natural” racial hierarchies and the dangers of miscegenation. Food was barely mentioned, except in the testimony that their cheap, rice-based diet was one reason the Chinese could compete so well against white workers, who needed red meat and bread to live. (In 1902, American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers expanded on this idea in an essay, “Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?”) Outside, workers marched and held mass meetings calling for the expulsion of the Chinese from California and the hiring of whites only. The following summer, a big demonstration in sympathy with railroad strikers back East turned ugly when the members of an anti-Coolie group joined in. The demonstrators marched to Chinatown, where they burned buildings, sacked laundries, and left four Chinese dead. White workers gathered in the empty sand-lot across from City Hall, where an Irish immigrant named Denis Kearney soon captured leadership of the crowd with his virulent anticapitalist, anti-Chinese oratory. In October 1877, he was elected president of the Workingmen’s Party, which demanded the expulsion of all Chinese from the United States, either by law or by force. Kearney became the leader of the anti-Chinese movement, helping Workingmen’s Party candidates win local offices and pushing for expulsion. As he barnstormed across the country, California’s Chinese citizens endured a spate of threats, beatings, shootings, and arson attacks. “Accidental” fires, in fact, became

a favorite method of emptying the state’s many Chinatowns. If whites had been unlikely to eat in Chinese restaurants before, now the culture of racial violence made a visit outright dangerous.

Kearney was more rabble-rouser than politician; audiences soon tired of his oratory, and he was reduced to selling coffee and doughnuts in a San Francisco squatter’s camp. But the anti-Chinese movement remained one of the most powerful political forces in the American West. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur, with the strong support of California’s congressional delegation and labor unions, signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which effectively blocked Chinese immigration and naturalization—the first U.S. law to bar a group from entering the country on the basis of its ethnicity. The only exceptions allowed in were merchants, teachers, students, and their personal servants. In 1892, the more onerous Geary Act, replacing the Exclusion Act, imposed even sterner restrictions on Chinese immigration and curtailed Chinese residents’ recourse to the courts. Across the West, many whites decided that now was the time for Chinese to leave their cities and towns, as local governments passed even more discriminatory laws. Many California Chinatowns, including in Pasadena, Santa Barbara, Oakland, San Jose, Sacramento, and Sonoma, were emptied under threats. On September 2, 1885, whites in the coal mining town of Rock Springs, Wyoming, decided that the Chinese no longer had any right to live and work there. A mob of men, mostly members of the Knights of Labor, surrounded the local Chinese settlement and opened fire with Winchester rifles. Any Chinese person who ran was shot, and the whites beat with gun butts anyone they could catch. Houses were burned to the ground, some with their Chinese residents inside. By nightfall, at least twenty-eight Chinese were dead, with many more injured and hiding in the hills.

Afterward, sixteen whites were arrested and charged with various crimes, but after a grand jury could find no one to testify against them, they were eventually released, to loud cheers from the community. Although eastern newspapers and politicians strongly condemned the violence, westerners generally supported the murderers. Indeed, the Rock Springs massacre seemed to embolden the anti-Chinese forces. In the coming months, Tacoma and Seattle, Washington, expelled their Chinese populations, and mobs across the Northwest attacked and often killed groups of Chinese miners, loggers, and farmworkers. Most Chinese, excepting those in enclaves in cities like San Francisco and Portland, decided that it was time to leave the West. In the late 1870s, they began to flee—to China on ships, never to return; across the border to Canada or Mexico; or, by the railroads they had built, to the big cities of the Northeast.

A Toothsome Stew

At the start of 1884, a New York writer named Edwin H. Trafton sent out an invitation to six fellow “connoisseurs of good living”:

Will you join a few other good fellows in chop-stick luck next Saturday night at the Chung Fah Low? As you of course know, this is the Chinese Delmonico’s of New York, at No.——Street (upstairs), sign of the Been Gin Law. Apropos of which the

chef

assures me in his most elegant pigeon English, “I cookee allee talkee,” which, being freely translated means, “I can cook in every language.” I know that you have a cosmopolitan palate and a cast-iron digestive apparatus, else I should not have asked you to come. The first course will be brought on at seven sharp, and stomach pumps may be ordered at nine o’clock.

1

The point of this dinner, aside from providing Trafton with the material for an article, was to answer the question “How do you do?” Or to phrase it as the Chinese would, “Have you eaten?” To “answer so comprehensive a conundrum,”

Trafton decided, “one must eat Chinese food; to become imbued with the spirit essential to a categorical, succinct and unequivocal response, one must have wielded chopsticks.” His six guests had eaten widely in the city, from the fare offered in the dining room of the newest, most elegant hotel—the Windsor on Fifth Avenue—to the pork and beans at Hitchcock’s dime restaurant down by the newspaper buildings on Park Row. For these gourmands, this feast would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, like “going up in a balloon; going down in a diving-bell; the sensation of being hanged, drowned or guillotined; what seasickness is like, or the eating of a Chinese dinner.”

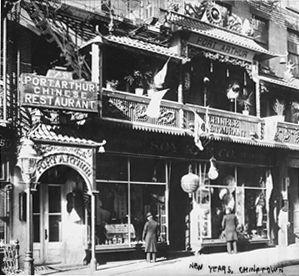

A few days before the event, Trafton ventured to Mott Street, the heart of New York’s Chinatown. At that time, there were only two Chinese restaurants on Mott, both at the south end of the street close to its intersection with Chatham Square. One was Chung Fah Low, above a Chinese grocery store at number 11. “Dingy, low-walled and ill-lighted,” this eatery was a step down from the elegant, three-story establishments of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Trafton climbed some rickety stairs and found himself in the restaurant’s back office, with two tables, a counter and shelves holding pots, chinaware, and an assortment of dried foodstuffs imported from China. The front room overlooking the street had been turned into the dining room, furnished with a single large table and six smaller ones, where placards with large Chinese characters shared the walls with cheap American color prints. Behind the office was the chef’s lair, the kitchen, which Trafton recognized as clean but nevertheless contained “ghastly piles” of plucked ducks, unidentified meats and vegetables, and pots “like witches’ caldrons” filled with mysterious broths emitting pungent odors. These sights and smells notwithstanding, Trafton was determined to order his banquet.

“What you want?” the owner asked, suspicious of the white man snooping around. When he heard that Trafton hoped to arrange a dinner party, the “round-faced, mooneyed” owner turned friendly, offering him a cigar, a cup of Chinese “rice gin,” and some tea. Never learning the owner’s name, Trafton called him “Ah Sin,” after the mild-looking but devious Chinese character in Bret Harte’s celebrated and widely reprinted poem “The Heathen Chinee.” Trafton and the owner were joined by the chef and the bookkeeper, and the group attempted to work out the evening’s menu. Unfortunately, the language barrier and Trafton’s ignorance of Chinese food made their task difficult. “Ah Sin” tried to help him by pulling out samples of the raw materials—“chunks of india-rubber, dried fish of all sorts and sizes, and some things that I could identify and classify a hundred years from now by their odors”—but Trafton could not imagine them made edible. Luckily, the writer’s Chinese friend, Hawk Ling, arrived just at this moment to help sort out the muddle. An agent for a wholesale grocer who wore American clothes and spoke “very good” English, Hawk Ling had probably recommended this restaurant as the site for Trafton’s dinner. Together, they worked out a menu of bird’s-nest soup, pungent-smelling “bull-fish,” dried oysters, Chinese codfish, duck, pork, tea, Chinese wine, and rice, for a total cost of $8—a very modest feast compared to what one could get in San Francisco.