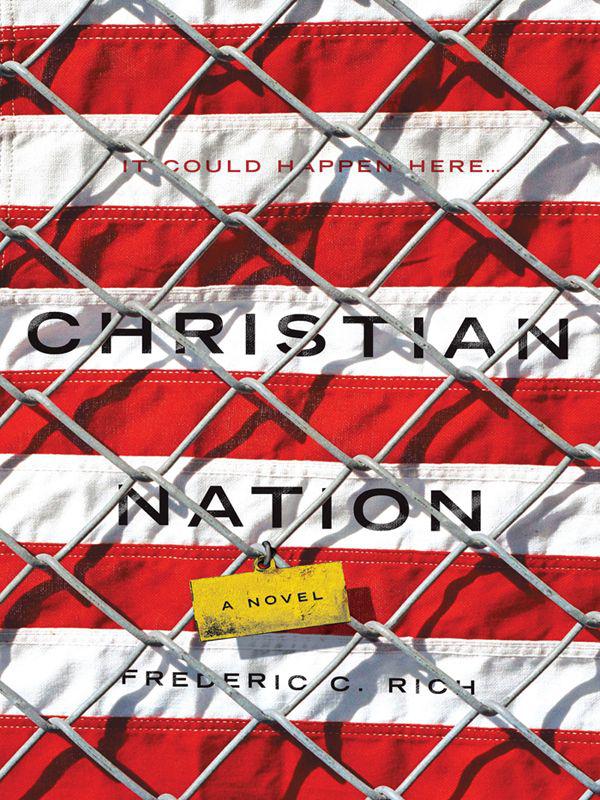

Christian Nation

CHRISTIAN NATION

— A Novel —

F

REDERIC

C. R

ICH

CONTENTS

What They Said They Would Do

(2029)

T

HIS NOVEL IS

a work of speculative fiction. The speculation is about one possible course of American history had the McCain/Palin campaign won the 2008 election. Except for certain historical events and statements by public figures prior to election night 2008, the narrative is entirely fictional. Accordingly, all statements and actions of actual public figures and organizations following election night 2008 are the product of the author’s imagination; the appearance of such statements and actions in a work of fiction does not constitute an assertion that such person or entity would speak or act in that way in those circumstances.

In contrast to the actual public figures and organizations appearing in the novel, the other characters and organizations are purely fictional, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual organizations, is entirely coincidental. As Evelyn Waugh put it so well, “I am not I: thou art not he or she: they are not they.”

Religion begins by offering magical aid to harassed and bewildered men; it culminates by giving to a people that unity of morals and belief which seems so favorable to statesmanship and art; it ends by fighting suicidally in the lost cause of the past. For as knowledge grows or alters continually, it clashes with mythology and theology, which change with geological leisureliness.

—Will and Ariel Durant,

The Story of Civilization

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

—Milan Kundera,

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

[W]ould-be totalitarian rulers usually start their careers by boasting of their past crimes and carefully outlining their future ones.

—Hannah Arendt,

The Origins of Totalitarianism

A

DAM TOLD ME TO START

by writing about what I feel now. Sitting here, I don’t feel much except the faint phantom ache of a wound long since healed. It was only six weeks ago that I met Adam Brown. He and his wife, Sarah, are downstairs asleep. In front of me is a beige IBM Selectric II typewriter, disconnected and without memory, immune from the insatiable probings of the Purity Web, and thus the ultimate contraband. A man I hardly know has seated me in front of a typewriter and told me to remember and write. I’ve spent a long time staring at the egg-like ball of little letters wondering why I am here and what they really want from me.

Here are the facts. I was a lawyer and then a fighter for the secular side in the Holy War that ended in 2020 following the siege of Manhattan. Like so many others, I earned my release from three years of rehabilitation on Governors Island by accepting Jesus Christ as my savior. For the past five years I have lived as a free citizen of the Christian Nation. This is the only truth I have allowed myself. Can I really now think and write the words that express a different truth? Here they are then: I am no longer chained in my cell, but for five years I have been bound even more firmly by the fifty commandments of The Blessing and the suffocating surveillance of the Purity Web. The cloak of collective righteousness lies heavy on the land.

Before coming here, I did not ask myself how it happened. I have neither remembered nor grieved. But now I discover that recollection is there, a paper’s edge from consciousness. When I close my eyes I find flickers of memory: Emilie’s empty martini glass on our terrace, drinking in the sun, the day after we broke up. And I remember looking at the hard empty glass and remembering her skin soft and warm and full of the same sun only the day before. Hard and soft. Stone and skin. Memories flicker and stutter, old film freezing in the projector, slipping, lurching forward. Dissolving.

Before, I was a lawyer. I was good with words. I was organized. I was not, frankly, much interested in my feelings, although I was pretty good at telling a story. A story should start at the beginning, but exactly where this one began is still a mystery to me.

What

is

clear to me is that they did what they said they would do. This morning, Adam pulled from the wall of old-fashioned gray metal file cabinets a tattered manila folder marked “2006” filled with clippings. In the folder I found a small glossy pamphlet from a group promoting “Christian Political Action.” An affable-looking man stares back at me from the cover. Inside is a letter dated November 2006, just a year after I started at the law firm.

When the Christian majority takes over this country, there will be no satanic churches, no more free distribution of pornography, no more talk of rights for homosexuals. After the Christian majority takes control, pluralism will be seen as immoral and evil, and the state will not permit anybody the right to practice evil.

That certainly is clear. I have read this little brochure over and over, trying to remember when I first heard this message, this promise. Was I listening? I was twenty-five in 2006. I was not very good at listening at that age, at least to things I didn’t want to hear. But what about the people who should have been listening? My parents, for example. I try to imagine my father picking up this brochure from the table in the foyer of our little wooden Catholic church in Madison, New Jersey. What would he have thought when reading these words? Closing my eyes, I can see him, still sandy haired at fifty, his athletic frame softened by scotch and a desk job. A decent man, reading a letter from a fellow Christian threatening to remake his world. He would have looked up, a shadow crossing his handsome face, then thrown the brochure in the little box where people neatly discarded the copies of hymn lyrics. He would have gone to play golf.

They promised, in 2006, that if they succeeded in acquiring political power, “the state will not permit anybody the right to practice evil.” In 2006 I was a first-year associate at the law firm. I try to remember. Had I ever heard of Rushdoony, North, Coe, Dobson, Perkins, or Farris? Did I know anything about Brownback, Palin, Bachmann, DeMint, Santorum, Coburn, or Perry? I do remember watching maudlin confessions of adultery from buffoonish TV preachers, stoic big-haired wives at their sides. I knew vaguely that out there somewhere in America, in an America that was to me a dimly understood foreign land, there existed people—lots of people—who called themselves “born again” or “evangelical.” I wonder what I thought that meant. Something ridiculous about believers flying up to heaven in a longed-for event called “the rapture,” leaving behind those not saved to endure the tribulations of the apocalypse. But I do remember being surprised when a banker client told me that the

Left Behind

series of apocalyptic novels and films had a US audience not so far behind that of the

Harry Potter

franchise. Both were fantastic stories of magic and miracles—one benign and one that proved to be an early symptom of something far darker.

It was 2009, I think, after President McCain’s sudden death, that my best friend, Sanjay, first explained to me that behind the public face of the Christian right was a strange mix of fundamentalist theologies, all different and often at odds with one another but aligned in supporting the election of politicians who believe they speak to and for God, aligned in seeking to have their religiously based morals adopted into law, and aligned in rejecting the traditional notion of a “wall of separation” between church and state. Of these fundamentalist theologies, the most extreme, and in many ways most influential, were dominionism and reconstructionism.

“Dominionism,” Sanjay explained, “holds that Christians need to establish a Christian reign on earth

before

Jesus returns for the second coming. Dominionists also believe that Christians in general have a God-given right to rule, but more particularly, in preparation for the second coming of Christ, that Christians have the

responsibility

to take over every aspect of political and civil society. And dominionism is often associated with a fringe theology called reconstructionism, which emphasizes that this reconstructed Christian-led society should be governed strictly accordingly to biblical law.”

How bored we were at first with Sanjay’s preoccupation with this dark strain of American belief. I didn’t know, and Sanjay only later discovered, that this dominionist outlook had influenced not only the Wasilla Assembly of God, the Pentecostal church attended by Sarah Palin in Alaska, but many thousands of others around the country. What had once been a fringe of exotic beliefs and schismatic sects had entered the religious mainstream in America.

Before the start of the Holy War, I delivered dozens of speeches warning of the political ambitions of the fundamentalists. Most of the time, I illustrated the meaning of dominionism with a single quote from a prominent evangelical “educator” from Tennessee, George Grant. I still remember it:

Christians have an obligation, a mandate, a commission, a holy responsibility to reclaim the land for Jesus Christ—to have dominion in civil structures, just as in every other aspect of life and Godliness. But it is dominion we are after. Not just a voice. It is dominion we are after. Not just influence. It is dominion we are after. Not just equal time. It is dominion we are after…. Thus, Christian politics has as its primary intent the conquest of the land—of men, families, institutions, bureaucracies, courts, and governments for the Kingdom of Christ.

Of course, it was only later that I made those speeches. After I made my choice. Before, for many years, I just couldn’t take it seriously. Closing my eyes again, I can hear Sanjay’s voice at a dinner at the East Side apartment I then shared with my girlfriend Emilie.

“It

is

serious,” he said, leaning forward. “What I am telling you, Greg, is that when they speak of turning America into a Christian Nation ruled in accordance with the Bible by those who purport to speak for God, this is not just rhetoric. It needs to be taken at face value. Right now, tens of millions of your fellow citizens believe—fanatically believe—there is nothing more important, and have been working for decades to acquire the political power to make it happen.”