Christine (46 page)

Authors: Steven King

“You're doing it too,” she said softly.

“What?”

“Calling it

she.”

I nodded, not letting go of her hands. “Yeah. I know. It's hard to stop. The thing is, Arnie wanted herâor it, or whatever that car isâfrom the first time he laid eyes on her. And I think now . . . I didn't then, but I do now . . . that LeBay wanted Arnie to have her just as badly; that he would have given her to him if it had come to that. It's like Arnie saw Christine and knew, and then LeBay saw Arnie and knew the same thing.”

Leigh pulled her hands free of mine and began to rub her elbows restlessly again. “Arnie said he paidâ”

“He paid, all right. And he's still paying. That is, if Arnie's left at all.”

“I don't understand what you mean.”

“I'll show you,” I said, “in a few minutes. First, let me give you the background.”

“All right.”

“LeBay had a wife and daughter. This was back in the fifties. His daughter died beside the road. She choked to death. On a hamburger.”

Leigh's face grew white, then whiter; for a moment she seemed as milky and translucent as clouded glass.

“Leigh!” I said sharply. “Are you all right?”

“Yes,” she said with a chilling placidity. Her color didn't improve. Her mouth moved in a horrid grimace that was perhaps intended to be a reassuring smile. “I'm fine.” She stood up. “Where is the bathroom, please?”

“There's one at the end of the hall,” I said. “Leigh, you look awful.”

“I'm going to vomit,” she said in that same placid voice, and walked away. She moved jerkily now, like a puppet, all the dancer's grace I had seen in her shadow now gone. She walked out of the room slowly, but when she was out of sight the rhythm of her stride picked up; I heard the bathroom door thrown open, and then the sounds. I leaned back against the sofa and put my hands over my eyes.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢

When she came back she was still pale but had regained a touch of her color. She had washed her face and there were still a few drops of water on her cheeks.

“I'm sorry,” I said.

“It's all right. It just . . . startled me.” She smiled wanly. “I guess that's an understatement.” She caught my eyes with hers. “Just tell me one thing, Dennis. What you said. Is it true? Really true?”

“Yeah,” I said. “It's true. And there's more. But do you really want to hear any more?”

“No,” she said. “But tell me anyway.”

“We could drop it,” I said, not really believing it.

Her grave, distressed eyes held mine. “It might be . . . safer . . . if we didn't,” she said.

“His wife committed suicide shortly after their daughter died.”

“The car . . .”

“. . . was involved.”

“How?”

“Leighâ”

“How?”

So I told herânot just about the little girl and her mother, but about LeBay himself, as his brother George had told me. His bottomless reservoir of anger. The kids who had made fun of his clothes and his bowl haircut. His escape into the Army, where everyone's clothes and haircuts were the same. The motor pool. The constant railing at the shitters, particularly those shitters who brought him their big expensive cars to be fixed at government expense. The Second World War. The brother, Drew, killed in France. The old Chevrolet. The old Hudson Hornet. And through it all, a steady and unchanging backbeat, the anger.

“That word,” Leigh murmured.

“What word?”

“Shitters.” She had to force herself to say it, her nose wrinkling in rueful and almost unconscious distaste.

“He

uses it Arnie.”

“I know.”

We looked at each other, and her hands found mine again.

“You're cold,” I said. Another bright remark from that font of wisdom, Dennis Guilder. I got a million of em.

“Yes. I feel like I'll never be warm again.”

I wanted to put my arms around her and didn't. I was afraid to. Arnie was still too much mixed up in things. The most awful thingâand it

was

awfulâwas how it seemed more and more that he was dead . . . dead, or under some weird enchantment.

“Did his brother say anything else?”

“Nothing that seems to fit.” But a memory rose like a bubble in still water and popped:

He was obsessed and he was angry, but he was not a monster,

George LeBay had told me.

At least . . . I

don't

think

he was.

It had seemed that, lost in the past as he had been, he had been about to say something more .. . and then had realized where he was and that he was talking to a stranger. What had he been about to say?

All at once I had a really monstrous idea. I pushed it away. It went . . . but it was hard work, pushing that idea. Like pushing a piano. And I could still see its outlines in the shadows.

I became aware that Leigh was looking at me very closely, and I wondered how much of what I had been thinking showed on my face.

“Did you take Mr. LeBay's address?” she asked.

“No.” I thought for a moment, and then remembered the funeral, which now seemed impossibly far back in time. “But I imagine the Libertyville American Legion Post has it. They buried LeBay and contacted the brother. Why?”

Leigh only shook her head and went to the window, where she stood looking out into the blinding day.

Shank of the year,

I thought randomly.

She turned back to me, and I was struck by her beauty again, calm and undemanding except for those high, arrogant cheekbonesâthe sort of cheekbones you might expect to see on a lady probably carrying a knife in her belt.

“You said you'd show me something,” she said. “What was it?”

I nodded. There was no way to stop now. The chain reaction had started. There was no way to shut it down.

“Go upstairs,” I said. “My room's the second door on the left. Look in the third drawer of my dresser. You'll have to dig under some of my undies, but they won't bite.”

She smiledâonly a little, but even a little was an improvement. “And what am I going to find? A Baggie of dope?”

“I gave that up last year,” I said, smiling back. “ 'Ludes this year. I finance my habit selling heroin down at the junior high.”

“What is it? Really?”

“Arnie's autograph,” I said, “immortalized on plaster.”

“His autograph?”

I nodded. “In duplicate.”

She found them, and five minutes later we were on the couch again, looking at two squares of plaster cast. They sat side by side on the glass-topped coffee table, slightly ragged on the sides, a little the worse for wear. Other names danced off into limbo on one of them. I had saved the casts, had even directed the nurse on where to cut them. Later I had cut out the two squares, one from the right leg, one from the left.

We looked at them silently:

on the right;

on the left.

Leigh looked at me, questioning and puzzled. “Those are pieces of yourâ”

“My casts, yeah.”

“Is it. . . a joke, or something?”

“No joke. I watched him sign both of them.” Now that it was out, there was a queer kind of loosening, of relief. It was good to be able to share this. It had been on my mind for a long time, itching and digging away.

“But they don't look anything alike.”

“You're telling me,” I said. “But Arnie isn't much like he used to be either. And it all goes back to that goddam car.” I poked savagely at the square of plaster on the left. “That isn't his signature. I've known Arnie almost all my life. I've seen his homework papers, I've seen him send away for things, I've watched him endorse his paychecks,

and that is not his signature.

The one on the right, yes. This one, no. You want to do something for me tomorrow, Leigh?”

“What?”

I told her. She nodded slowly. “For us.”

“Huh?”

“I'll do it for us. Because we have to do something, don't we?”

“Yes,” I said. “I guess so. You mind a personal question?”

She shook her head, her remarkable blue eyes never leaving mine.

“How have you been sleeping lately?”

“Not so well,” she said. “Bad dreams. How about you?”

“No. Not so good.”

And then, because I couldn't help myself anymore, I put my hands on her shoulders and kissed her. There was a momentary hesitation, and I thought she was going to draw away . . . then her chin came up and she kissed me back, firmly and fully. Maybe it was sort of lucky at that, me being mostly immobilized.

When the kiss was over she looked into my eyes, questioning.

“Against the dreams,” I said, thinking it would come out stupid and phony-smooth, the way it looks on paper, but instead it sounded shaky and almost painfully honest.

“Against the dreams,” she repeated gravely, as if it were a talisman, and this time she inclined her head toward me and we kissed again with those two ragged squares of plaster staring up at us like blind white eyes with Arnie's name written across them. We kissed for the simple animal comfort that comes with animal contactâsure, that, and something more, starting to be something moreâand then we held each other without talking, and I don't think we were kidding ourselves about what was happeningâat least not entirely. It was comfort, but it was also good old sexâfull, ripe, and randy with teenage hormones. And maybe it had a chance to be something fuller and kinder than just sex.

But there was something else in those kissesâI knew it, she knew it, and probably you do too. That other thing was a shameful sort of betrayal. I could feel eighteen years of memories cry outâthe ant farms, the chess games, the movies, the things he had taught me, the times I had kept him from getting killed. Except maybe in the end, I hadn't. Maybe I had seen the last of himâand a poor, rag-tag end at thatâon Thanksgiving night, when he brought me the turkey sandwiches and beer.

I don't think it occurred to either of us that until then we had done nothing unforgivable to Arnieânothing that might anger Christine. But now, of course, we had.

44

Detective Work

What happened in the next three weeks or so was that Leigh and I played detective, and we fell in love.

She went down to the Municipal Offices the next day and paid fifty cents to have two papers Xeroxedâthose papers go to Harrisburg, but Harrisburg sends a copy back to the town.

This time my family was home when Leigh arrived. Ellie peeked in on us whenever she got the chance. She was fascinated by Leigh, and I was quietly amused when, about a week into the new year, she started wearing her hair tied back as Leigh did. I was tempted to get on her case about it . . . and withstood the temptation. Maybe I was growing up a little bit (but not enough to keep from sneaking one of her Yodels when I saw one hidden behind the Tupperware bowls of leftovers in the refrigerator).

Except for Ellie's occasional peeks, we had the living room mostly to ourselves that next afternoon, the twenty-seventh of December, after the social amenities had been observed. I introduced Leigh to my mother and father, my mom served coffee, and we talked. Elaine talked the mostâchattering about her school and asking Leigh all sorts of questions about ours. At first I was annoyed, and then I was grateful. Both my parents are the soul of middle-class politeness (if my mom was being led to the electric chair and bumped into the chaplain, she would excuse herself), and I felt pretty clearly that they liked Leigh, but it was also obviousâto me, at leastâthat they were puzzled and a little uncomfortable, wondering where Arnie fit into all this.

Which was what Leigh and I were wondering ourselves, I guess. Finally they did what parents usually do when they're puzzled in such situationsâthey dismissed it as kid business and went about their own business. Dad excused himself first, saying that his workshop in the basement was in its usual post-Christmas shambles and he ought to start doing something about it. Mom said she wanted to do some writing.

Ellie looked at me solemnly and said, “Dennis, did Jesus have a dog?”

I cracked up and so did Ellie. Leigh sat watching us laugh, smiling politely the way outsiders do when it's a family joke.

“Split, Ellie,” I said.

“What'll you do if I won't?” she asked, but it was only routine brattiness; she was already getting up.

“Make you wash my underwear,” I said.

“The hell you

will!”

Ellie declared grandly, and left the room.

“My little sister,” I said.

Leigh was smiling. “She's great.”

“If you had to live with her full-time you might change your mind. Let's see what you've got.”

Leigh put one of the Xerox copies on the glass coffee table where the pieces of my casts had been yesterday.

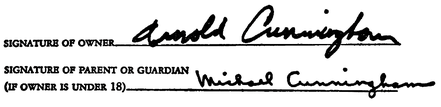

It was the re-registration of a used car, 1958 Plymouth sedan (4-door), red and white. It was dated November 1, 1978, and signed Arnold Cunningham. His father had co-signed for him:

“What does that look like to you?” I asked.

“One of the signatures on one of the squares you showed me,” she said. “Which one?”

“It's the way he signed just after I got crunched in Ridge Rock,” I said. “It's the way his signature always looked. Now let's see the other one.”

She put it down beside the first. This was a registration slip for a new car, 1958 Plymouth sedan (4-door), red and white. It was dated November 1, 1957âI felt a nasty jolt at that exact similarity, and one look at Leigh's face told me she had seen it too.

“Look at the signature,” she said quietly.

I did.

This was the handwriting Arnie had used on Thanksgiving evening; you didn't have to be a genius or a handwriting expert to see that. The names were different, but the writing was exactly the same.

Leigh reached for my hands, and I took hers.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢

What my father did in his basement workshop was make toys. I suppose that might sound a little weird to you, but it's his hobby. Or maybe something more than a hobbyâI think there might have been a time in his life when he had to make a difficult choice between going to college and going out on his own to become a toymaker. If that's true, then I guess he chose the safe way. Sometimes I think I see it in his eyes, like an old ghost not quite laid to rest, but that is probably only my imagination, which used to be a lot less active than it is now.

Ellie and I were the chief beneficiaries, but Arnie had also found some of my father's toys under various Christmas trees and beside various birthday cakes, as had Ellie's closest childhood friend Aimee Carruthers (long since moved to Nevada and now referred to in the doleful tones reserved for those who have died young and senselessly) and many other chums.

Now my dad gave most of what he made to the Salvation Army 400 Fund, and before Christmas the basement always reminded me of Santa's workshopâuntil just before Christmas it would be filled with neat cardboard cartons containing wooden trains, little toolchests, Erector-set clocks that really kept time, stuffed animals, a small puppet theater or two. His main interest was in wooden toys (up until the Viet Nam war he had made battalions of toy soldiers, but in the last five years or so they had been quietly phased outâeven now I'm not sure he was aware he was doing it), but like a good spray hitter, my dad went to all fields. During the week after Christmas there was a hiatus. The workshop would seem terribly empty, with only the sweet smell of sawdust to remind us that the toys had ever been there.

In that week he would sweep, clean, oil his machinery, and get ready for next year. Then, as the winter wore on through January and February, the toys and the seeming junk that would become parts of toys would begin appearing againâtrains and jointed wooden ballerinas with red spots of color on their cheeks, a box of stuffing raked out of someone's old couch that would later end up in a bear's belly (my father called every one of his bears Owen or OliveâI had worn out six Owen Bears between infancy and second grade, and Ellie had worn out a like number of Olive Bears), little snips of wire, buttons, and flat, disembodied eyes scattered across the worktable like something out of a pulp horror story. Last, the liquor-store boxes would appear, and the toys would again be packed into them.

In the last three years he had gotten three awards from the Salvation Army, but he kept them hidden away in a drawer, as if he was ashamed of them. I didn't understand it then and don't nowânot completelyâbut at least I know it wasn't shame. My father had nothing to be ashamed of.

I worked my way down that evening after supper, clutching the bannister madly with one arm and using my other crutch like a ski-pole.

“Dennis,” he said, pleased but slightly apprehensive. “You need any help?”

“No, I got it.”

He put his broom aside by a small yellow drift of shavings and watched to see if I was really going to make it. “How about a push, then?”

“Ha-ha, very funny.”

I got down, semi-hopped over to the big easy chair my father keeps in the corner beside our old Motorola black-and-white, and sat down.

Plonk.

“How you doing?” he asked.

“Pretty good.”

He brushed up a dustpanful of shavings, dumped them into his wastebarrel, sneezed, and brushed up some more. “No pain?”

“No. Well. . . some.”

“You want to be careful of stairs. If your mother had seen what you just didâ”

I grinned. “She'd scream, yeah.”

“Where

is

your mother?”

“She and Ellie went over to the Rennekes'. Dinah Renneke got a complete library of Shaun Cassidy albums for Christmas. Ellie is

green.”

“I thought Shaun was out,” my father said.

“I think she's afraid fashion might be doubling back on her.”

Dad laughed. Then there was a companionable silence for a while, me sitting, him sweeping. I knew he'd get around to it, and presently he did.

“Leigh,” he said, “used to go with Arnie, didn't she?”

“Yes,” I said.

He glanced at me, then down at his work again. I thought he would ask me if I thought that was wise, or maybe mention that one fellow stealing another fellow's girl was not the best way to promote continued friendship and accord. But he said neither of those things.

“We don't see much of Arnie anymore. Do you suppose he's ashamed of the mess he's in?”

I had the feeling that my father didn't believe that at all; that he was simply testing the wind.

“I don't know,” I said.

“I don't think he has much to worry about. With Darnell dead”âhe tipped his dustpan into the barrel and the shavings slid in with a soft

flump

â“I doubt if they'll even bother to prosecute.”

“No?”

“Not Arnie. Not on anything serious. He may be fined, and the judge will probably lecture him, but nobody wants to put an indelible black mark on the record of a nice young suburban white boy who is bound for college and a fruitful place in society.”

He shot me a sharp questioning look, and I shifted in the chair, suddenly uncomfortable.

“Yeah, I suppose.”

“Except he's not really like that anymore, is he, Dennis?”

“No. He's changed.”

“When was the last time you actually saw him?”

“Thanksgiving.”

“Was he okay then?”

I shook my head slowly, suddenly feeling like crying and blurting it all out. I had felt that way once before and hadn't; I didn't this time, either, but for a different reason. I remembered what Leigh had said, about being nervous for her parents on Christmas Eve. And it seemed to me now that the fewer the people who knew about our suspicions, the safer . . . for them.

“What's wrong with him?”

“I don't know.”

“Does Leigh?”

“No. Not for sure. We have. . . some suspicions.”

“Do you want to talk about them?”

“Yes. In a way I do. But I think it would be better if I didn't.”

“All right,” he said. “For now.”

He swept the floor. The sound of the hard bristles on the concrete was almost hypnotic.

“And maybe you had better talk to Arnie before too much longer.”

“Yeah. I was thinking about that.” But it wasn't an interview I looked forward to.

There was another period of silence. Dad finished sweeping and then glanced around. “Looks pretty good, huh?”

“Great, Dad.”

He smiled a little sadly and lit a Winston. Since his heart attack he had given the butts up almost completely, but he kept a pack around, and every now and then he'd have oneâusually when he felt under stress. “Bullshit. It looks empty as hell.”

“Well. . . yeah.”

“You want a hand upstairs, Dennis?”

I got my crutches under me. “I wouldn't turn it down.”

He looked at me and snickered. “Long John Silver. All you need is the parrot.”

“Are you going to stand there giggling or give me a hand?”

“Give you a hand, I guess.”

I slung an arm over his shoulder, feeling somehow like a little kid againâit brought back almost forgotten memories of him carrying me upstairs to bed on Sunday nights, after I started to doze off halfway through the

Ed Sullivan Show.

The smell of his aftershave was just the same.

At the top he said, “Step on me if I'm getting too personal, Denny, but Leigh's not going with Arnie anymore, is she.”

“No, Dad.”

“Is she going with you?”

“I. . . well, I don't really know. I guess not.”

“Not

yet,

you mean.”

“Wellâyeah, I guess so.” I was starting to feel uncomfortable, and it must have showed, but he pushed on anyway.

“Would it be fair to say that maybe she broke it off with Arnie because he wasn't the same person anymore?”

“Yes. I think that would be fair to say.”

“Does he know about you and Leigh?”

“Dad, there's nothing to know . . . at least, not yet.”