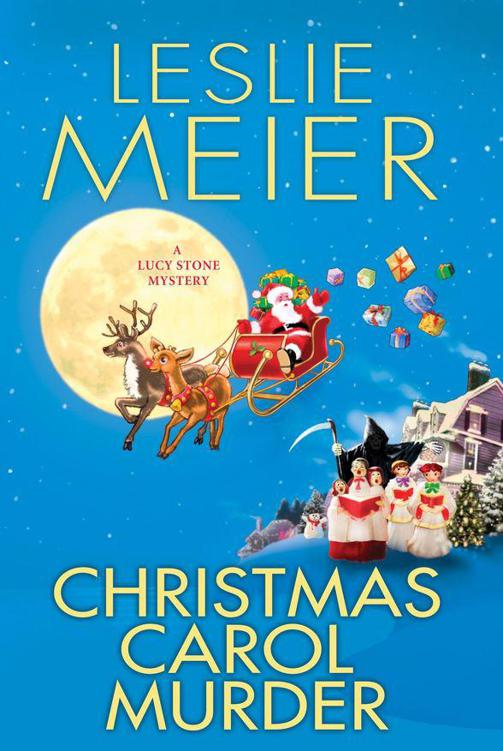

Christmas Carol Murder (A Lucy Stone Mystery)

Read Christmas Carol Murder (A Lucy Stone Mystery) Online

Authors: Leslie Meier

Books by Leslie Meier

MISTLETOE MURDER

TIPPY TOE MURDER

TRICK OR TREAT MURDER

BACK TO SCHOOL MURDER

VALENTINE MURDER

CHRISTMAS COOKIE MURDER

TURKEY DAY MURDER

WEDDING DAY MURDER

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

FATHER’S DAY MURDER

STAR SPANGLED MURDER

NEW YEAR’S EVE MURDER

BAKE SALE MURDER

CANDY CANE MURDER

ST. PATRICK’S DAY MURDER

MOTHER’S DAY MURDER

WICKED WITCH MURDER

GINGERBREAD COOKIE MURDER

ENGLISH TEA MURDER

CHOCOLATE COVERED MURDER

EASTER BUNNY MURDER

CHRISTMAS CAROL MURDER

TIPPY TOE MURDER

TRICK OR TREAT MURDER

BACK TO SCHOOL MURDER

VALENTINE MURDER

CHRISTMAS COOKIE MURDER

TURKEY DAY MURDER

WEDDING DAY MURDER

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

FATHER’S DAY MURDER

STAR SPANGLED MURDER

NEW YEAR’S EVE MURDER

BAKE SALE MURDER

CANDY CANE MURDER

ST. PATRICK’S DAY MURDER

MOTHER’S DAY MURDER

WICKED WITCH MURDER

GINGERBREAD COOKIE MURDER

ENGLISH TEA MURDER

CHOCOLATE COVERED MURDER

EASTER BUNNY MURDER

CHRISTMAS CAROL MURDER

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

A Lucy Stone Mystery

CHRISTMAS CAROL MURDER

LESLIE MEIER

KENSINGTON BOOKS

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Books by Leslie Meier

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Copyright Page

Prologue

I

VCET

VCET

That was easy, thought Jake Marlowe, cackling merrily as he wrote EVICT in the blanks of the word jumble with a small stub of pencil—waste not, want not was his favorite saying, and he was certainly not going to discard a perfectly usable pencil, even if it was a bit hard to grip with his arthritic hands—and applied himself to the riddle: “Santa’s favorite meal.” Then, doubting his choice, he wondered if the correct answer was really CIVET. But no, then the

I

and

C

wouldn’t be in the squares with circles inside indicating the letters needed to solve the riddle, and he needed them for MILK AND COOKIES, which was undoubtedly the correct answer.

I

and

C

wouldn’t be in the squares with circles inside indicating the letters needed to solve the riddle, and he needed them for MILK AND COOKIES, which was undoubtedly the correct answer.

He tossed the paper and pencil on the kitchen table, where the dirty breakfast dishes vied for space with a month’s worth of morning papers and junk mail and, pressing his hands on the table for support, rose to his feet. He pushed his wire-rimmed glasses back up his beaky nose and adjusted the belt on his black and brown striped terry cloth bathrobe, lifting the collar against the chill. The antique kerosene heater he used rather than the central heating, which guzzled expensive oil, didn’t provide much heat. He picked up his empty coffee mug and shuffled over to the counter where the drip coffeepot sat surrounded by old coffee cans, empty milk containers, and assorted bottles. He filled his stained, chipped mug with the

Downeast Mortgage Company

logo and carried it back to the table, sitting down heavily in his captain’s chair, and preparing to settle in with the

Wall Street Journal

.

Downeast Mortgage Company

logo and carried it back to the table, sitting down heavily in his captain’s chair, and preparing to settle in with the

Wall Street Journal

.

I

NTEREST

R

ATES

H

IT

R

ECORD

L

OW

read the headline, causing him to scowl in disapproval. What were the feds thinking? The economy would never recover at this rate, not if investors couldn’t reap some positive gains. He snorted and gulped some coffee. What could you expect? People didn’t save anymore; they spent more than they had and then they borrowed to make up the difference, and when they got in trouble, which was inevitable, they expected the government to bail them out. He folded the paper with a snap and added it to the stack beside his chair, a stack that was in danger of toppling over.

NTEREST

R

ATES

H

IT

R

ECORD

L

OW

read the headline, causing him to scowl in disapproval. What were the feds thinking? The economy would never recover at this rate, not if investors couldn’t reap some positive gains. He snorted and gulped some coffee. What could you expect? People didn’t save anymore; they spent more than they had and then they borrowed to make up the difference, and when they got in trouble, which was inevitable, they expected the government to bail them out. He folded the paper with a snap and added it to the stack beside his chair, a stack that was in danger of toppling over.

Jake had saved every issue of the

Portland Press Herald

that he’d ever received, as well as his copies of the

Wall Street Journal

, and since he was well into his sixties that was quite a lot of papers. They covered every surface in his house, were stacked on windowsills and piled on the floor, filling most of the available space and leaving only narrow pathways that wound from room to room.

Portland Press Herald

that he’d ever received, as well as his copies of the

Wall Street Journal

, and since he was well into his sixties that was quite a lot of papers. They covered every surface in his house, were stacked on windowsills and piled on the floor, filling most of the available space and leaving only narrow pathways that wound from room to room.

Jake never threw anything away. He literally had every single item he’d ever owned stashed somewhere in the big old Victorian house. Pantry shelves were filled with empty jelly jars, kitchen drawers were packed to bursting with plastic bags, closets in the numerous bedrooms were stuffed with old clothes and dozens of pairs of old shoes, the leather cracked and the toes curling up. Beds no one ever slept in were covered with boxes of junk, dresser drawers that were never opened contained old advertising flyers, dead batteries, and blown lightbulbs. And everywhere, filling every bit of square footage, were stacks of newspapers. They crawled up the walls, they blocked windows, they turned the house into a maze of narrow, twisting corridors.

When the grandfather clock in the hall chimed nine, time for Jake to get dressed, he shuffled into the next room, once the dining room but now his bedroom, where he slept on an ancient daybed. He sat down heavily, amid the musty sheets and blankets, and began carefully removing the plastic laundry bag from his heavily starched shirt. He was folding up the plastic bag, intending to add it to the sizeable collection he was accumulating beneath his bed, when he heard the neighbor’s dog bark.

It was the mail, right on time; he nodded with satisfaction. Jake was one of the first on Wilf Lundgren’s route, and the mail was always delivered around nine, barring the occasional storm delay. Fred, the elderly beagle belonging to his neighbor and dentist, Dr. Cyrus Frost, always announced Wilf’s arrival, as well as that of the FedEx truck, the garbage truck, and any proselytizing Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Jake was expecting his bank statement, which had been delayed a day because of the Thanksgiving holiday, so he decided to collect the mail even though he wasn’t dressed. Not that it mattered. He was decent, covered chin to ankles in the long johns he wore all winter; the thick robe was warm and he had fleece-lined slippers. He hurried down the drive, eager to see if the bank statement had come, and as he approached the mailbox he noticed something large and colorful sticking out of it.

Reaching the box, which topped a post next to the street, he examined a padded mailing envelope printed with a red and green Christmas design protruding from the box. A present? He pulled it out, studying the design of candy canes and gingerbread men. It was addressed to him, he saw, and there was a label that warned

Do Not Open Till Christmas

. It was only the day after Thanksgiving, a bit early for a Christmas gift, perhaps, but Thanksgiving was the official beginning of the Christmas season. Not that he had partaken of the annual feast the day before; he and his partner Ben Scribner had gone to the office as usual, but they had agreed to give their secretary, Elsie Morehouse, the day off. They hadn’t wanted to, but Elsie had pointed out in no uncertain terms that it was a legal holiday and she was entitled to take it.

Do Not Open Till Christmas

. It was only the day after Thanksgiving, a bit early for a Christmas gift, perhaps, but Thanksgiving was the official beginning of the Christmas season. Not that he had partaken of the annual feast the day before; he and his partner Ben Scribner had gone to the office as usual, but they had agreed to give their secretary, Elsie Morehouse, the day off. They hadn’t wanted to, but Elsie had pointed out in no uncertain terms that it was a legal holiday and she was entitled to take it.

Jake pulled the rest of his mail, a couple of plain white envelopes, out of the box. He noted with satisfaction that the bank statement had finally arrived, and looked forward to balancing it. He took pride in the fact that should there be a discrepancy between his calculations and those of the bank, his would undoubtedly be correct and the error would be the bank’s. But first things first. He hurried back to the house, hugging the package to his chest, chuckling merrily.

A present. He hadn’t received a present in a long time. Who could it be from? He studied the return address, but it didn’t make any sense.

Santa Claus,

it read.

North Pole, Alaska.

It must be some sort of joke. Ben Scribner wasn’t known for jokes, so he doubted it was from him. Besides, despite their long partnership of over thirty years, they never exchanged presents.

Santa Claus,

it read.

North Pole, Alaska.

It must be some sort of joke. Ben Scribner wasn’t known for jokes, so he doubted it was from him. Besides, despite their long partnership of over thirty years, they never exchanged presents.

Perhaps it was from a grateful customer, a home owner who had the good sense to appreciate the current low interest rates, sometimes under four percent. That was unlikely, however, thought Jake. Real estate wasn’t what it once was—prices were falling and most home owners owed more than their houses were worth.

The economy was bad, no doubt about it. Maybe some tradesman was expressing appreciation for his custom. He did have a faucet replaced this year; maybe it was a thank you from Earle Plumbing. Ed Earle was probably thankful for one customer who paid on time, cash on the barrelhead. Come to think of it, he’d hired the electrician, too, to fix a busted wall switch. Al Lucier was no doubt appreciative of his prompt payment. Or maybe it was from his insurance agent, who might be sending something more substantial than the usual calendar this year. Only one way to find out, he decided, clutching the package to his chest and hurrying out of the cold and back into the slightly warmer house.

Once inside, with the kitchen door closed behind him, he set the envelopes on the kitchen counter, on top of a stack of empty egg cartons, and carefully examined the package. Only one way to find out what was inside, he decided, and that was to open it. Practically bursting with anticipation, he ripped off the flap.

Chapter One

W

hen the first foreclosure sale of the Great Recession took place in Tinker’s Cove, Maine,

Pennysaver

reporter Lucy Stone expected a scene right out of a silent movie. The auctioneer would be a slimy sort of fellow who ran his fingers along his waxed and curled mustache and cackled evilly, the banker would be a chubby chap whose pocket watch dangled from a thick gold chain stretched across his round stomach, and a burly sheriff would be forcibly evicting a noticeably hungry and poorly clad family from their home while his deputies tossed furniture and personal belongings onto the lawn.

hen the first foreclosure sale of the Great Recession took place in Tinker’s Cove, Maine,

Pennysaver

reporter Lucy Stone expected a scene right out of a silent movie. The auctioneer would be a slimy sort of fellow who ran his fingers along his waxed and curled mustache and cackled evilly, the banker would be a chubby chap whose pocket watch dangled from a thick gold chain stretched across his round stomach, and a burly sheriff would be forcibly evicting a noticeably hungry and poorly clad family from their home while his deputies tossed furniture and personal belongings onto the lawn.

The reality, which she discovered when she joined a small group of people gathered in front of a modest three-bedroom ranch, was somewhat different. For one thing, the house was vacant. The home owners had left weeks ago, according to a neighbor. “When Jim lost his job at the car dealership they realized they couldn’t keep up the payments on Patty’s income—she was a home health aide—so they packed up their stuff and left. Patty’s mom has a B and B on Cape Cod, so she’s going to help out there, and Jim’s got himself enrolled in a nursing program at a community college.”

“That sounds like a good plan,” Lucy said, feeling rather disappointed as she’d hoped to write an emotion-packed human interest story.

“They’re not getting off scot-free,” the neighbor said, a young mother with a toddler on her hip. “They’ll lose all the money they put in the house—bamboo floors, granite countertops, not to mention all the payments they made—and the foreclosure will be a blot on their credit rating for years. . . .” Her voice trailed off as the auctioneer called for attention and began reading a lot of legalese.

While he spoke, Lucy studied the individuals in the small group, who she assumed were planning to bid on the property in hopes of snagging a bargain. One or two were even holding white envelopes, most likely containing certified checks for the ten thousand dollars down specified in the ad announcing the sale.

But when the auctioneer called for bids, Ben Scribner, a partner in Downeast Mortgage, which held the note, opened with $185,000, the principal amount. That was more than the bargain hunters were prepared to offer, and they began to leave. Seeing no further offers, the auctioneer declared the sale over and the property now owned by the mortgage company.

Ben, who had thick white hair and ruddy cheeks, was dressed in the casual outfit of khaki pants and button-down oxford shirt topped by a barn coat favored by businessmen in the coastal Maine town. He was a prominent citizen who spoke out at town meetings, generally against any measure that would raise taxes. His company, Downeast Mortgage, provided financing for much of the region and there were few people in town who hadn’t done business with him and his partner, Jake Marlowe. Marlowe was well known as a cheapskate, living like a solitary razor clam in that ramshackle Victorian mansion, and he was a fixture on the town’s Finance Committee where he kept an eagle eye on the town budget.

Since that October day three years ago, there had been many more foreclosures in Tinker’s Cove as the economy ground to a standstill. People moved in with relatives, they rented, or they moved on. What they didn’t do was launch any sort of protest, at least not until now.

The fax announcing a Black Friday demonstration had come into the

Pennysaver

from a group at Winchester College calling itself the Social Action Committee, or SAC, which claimed to represent “the ninety-nine percent.” The group was calling for an immediate end to foreclosures and was planning a demonstration at the Downeast Mortgage office on the Friday after Thanksgiving, which Lucy had been assigned to cover.

Pennysaver

from a group at Winchester College calling itself the Social Action Committee, or SAC, which claimed to represent “the ninety-nine percent.” The group was calling for an immediate end to foreclosures and was planning a demonstration at the Downeast Mortgage office on the Friday after Thanksgiving, which Lucy had been assigned to cover.

When she arrived, a few minutes before the appointed time of nine a.m., there was no sign of any demonstration. But when the clock on the Community Church chimed the hour, a row of marchers suddenly issued from the municipal parking lot situated behind the stores that lined Main Street. They were mostly college students who for one reason or other hadn’t gone home for the holiday, as well as a few older people, professors and local residents Lucy recognized. They were bundled up against the November chill in colorful ski jackets, and they were carrying signs and marching to the beat of a Bruce Springsteen song issuing from a boom box. The leader, wearing a camo jacket and waving a megaphone, was a twenty-something guy with a shaved head.

“What do we want?” he yelled, his voice amplified and filling the street.

“Justice!” the crowd yelled back.

“When do we want it?” he cried.

“NOW!” roared the crowd.

Lucy immediately began snapping photos with her camera, and jogged along beside the group. When they stopped in front of Downeast Mortgage, and the leader got up on a milk crate to speak, she pulled out her notebook. “Who is that guy?” she asked the kid next to her.

“Seth Lesinski,” the girl replied.

“Do you know how he spells it?”

“I think it’s L-E-S-I-N-S-K-I.”

“Got it,” Lucy said, raising her eyes and noticing a girl who looked an awful lot like her daughter Sara. With blue eyes, blond hair, and a blue crocheted hat she’d seen her pull on that very morning, it was definitely Sara.

“What are you doing here?” she demanded, confronting her college freshman daughter. “I thought you have a poli sci class now.”

Sara rolled her eyes. “Mo-om,” she growled. “Later, okay?”

“No. You’re supposed to be in class. Do you know how much that class costs? I figured it out. It’s over a hundred dollars per hour and you’re wasting it.”

“Well, if you’re so concerned about waste, why aren’t you worried about all the people losing their homes?” Sara countered. “Huh?”

“I am concerned,” Lucy said.

“Well, you haven’t shown it. There hasn’t been a word in the paper except for those legal ads announcing the sales.”

Lucy realized her daughter had a point. “Well, I’m covering it now,” she said.

“So why don’t you be quiet and listen to Seth,” Sara suggested, causing Lucy’s eyes to widen in shock. Sara had never spoken to her like that before, and she was definitely going to have a talk with her. But now, she realized, she was missing Seth’s speech.

“Downeast Mortgage is the primary lender in the county and they have foreclosed on dozens of properties, and more foreclosures are scheduled. . . .”

The crowd booed, until Seth held up his hand for silence.

“They’ll have you believe that people who miss their payments are deadbeats, failures, lazy, undeserving, irresponsible.... You’ve heard it all, right?”

There was general agreement, and people nodded.

“But the truth is different. These borrowers qualified for mortgages, had jobs that provided enough income to cover the payments, but then the recession came and the jobs were gone. Unemployment in this county is over fourteen percent. That’s why people are losing their homes.”

Lucy knew there was an element of truth in what Lesinski was saying. She knew that even the town government, until recently the region’s most dependable employer, had recently laid off a number of employees and cut the hours of several others. In fact, scanning the crowd, she recognized Lexie Cunningham, who was a clerk in the tax collector’s office. A big guy in a plaid jacket and navy blue watch cap was standing beside her, probably her husband. Lucy decided they might be good interview subjects and approached them.

“Hi, Lucy,” Lexie said, with a little smile. She looked as if she’d lost weight, thought Lucy, and her hair, which had been dyed blond, was now showing dark roots and was pulled back unattractively into a ponytail. “This is my husband, Zach.”

“I’m writing this up for the paper,” Lucy began. “Can you tell me why you’re here today?”

“’Cause we’re gonna lose our house, that’s why,” Zach growled. “Downeast sent us a notice last week.”

“My hours were cut, you know,” Lexie said. “Now I don’t work enough hours to get the health insurance benefit. Because of that we have to pay the entire premium—it’s almost two thousand dollars a month, which is actually more than I now make. We can’t pay both the mortgage and the health insurance and we can’t drop the health insurance because of Angie—she’s got juvenile kidney disease.”

“I didn’t know,” Lucy said, realizing they were faced with an impossible choice.

“We don’t qualify for assistance. Zach makes too much and we’re over the income limit by a couple hundred dollars. But the health insurance is expensive, more than our mortgage. We were just getting by but then Angie had a crisis and the bills started coming. . . .”

“But you do have health insurance,” Lucy said.

“It doesn’t cover everything. There are copays and coinsurance and exclusions. . . .”

“Downeast is a local company—have you talked to Marlowe and Scribner? I bet they’d understand. . . .”

Zach started laughing, revealing a missing rear molar. “Understand? All those guys understand is that I agreed to pay them nine hundred and forty-five dollars every month. That’s my problem, is what they told me.”

“So that’s why we’re out here, demonstrating,” Lexie said, as a sudden huge boom shook the ground under their feet.

“What the . . . ?” Everyone was suddenly silent, shocked by the loud noise and the reverberations.

“Gas?” somebody asked. They could hear a dog barking.

“Fire,” said a kid in a North Face jacket, pointing to the column of black smoke that was rising into the sky.

“Parallel Street,” Zach said, as sirens wailed and bright red fire trucks went roaring down the street, lights flashing.

A couple of guys immediately took off down the street, running after the fire trucks, and soon the crowd followed. Lucy always felt a little uncomfortably ghoulish at times like this, but she knew it was simply human nature to want to see what was going on. She knew it was the same impulse that caused people to watch CNN and listen to the car radio and even read the

Pennysaver

.

Pennysaver

.

So she joined the crowd, hurrying along beside Sara and her friend Amy, rounding the corner onto Maple Street, where the smell of burning was stronger, and on to Parallel Street, which, as its name suggested, ran parallel to Main Street. Unlike Main Street, which was the town’s commercial center, Parallel was a residential street filled with big old houses set on large properties. Most had been built in the nineteenth century by prosperous sea captains, eager to showcase their success. Nowadays, a few were still single family homes owned by members of the town’s professional elite, but others had been subdivided into apartments and B and Bs. It was a pleasant street, lined with trees, and the houses were generally well maintained. In the summer, geraniums bloomed in window boxes and the sound of lawn mowers was frequently heard. Now, some houses still displayed pumpkin and gourd decorations for Thanksgiving while others were trimmed for Christmas, with window boxes filled with evergreen boughs and red-ribboned wreaths hung on the front doors. All except for one house, a huge Victorian owned by Jake Marlowe that was generally considered a blight on the neighborhood.

The old house was a marvel of Victorian design, boasting a three-story tower, numerous chimneys, bay windows, a sunroom, and a wraparound porch. Passing it, observing the graying siding that had long since lost its paint and the sagging porch, Lucy always imagined the house as it had once been. Then, she thought, the mansion would have sported a colorful paint job and the porch would have been filled with wicker furniture, where long-skirted ladies once sat and sipped lemonade while they observed the passing scene.

It had always seemed odd to her that a man whose business was financing property would take such poor care of his own, but when she’d interviewed a psychiatrist for a feature story about hoarders she began to understand that Jake Marlowe’s cheapness was a sort of pathology. “Hoarders can’t let anything go; it makes them unbearably anxious to part with anything,” the psychiatrist had explained to her.

Now, standing in front of the burning house, Lucy saw that Jake Marlowe was going to lose everything.

“Wow,” she said, turning to Sara and noticing how her daughter’s face was glowing, bathed in rosy light from the fire. Everyone’s face was like that, she saw, as they watched the orange flames leaping from the windows, running across the tired old porch, and even erupting from the top of the tower. No one could survive such a fire, she thought. It was fortunate it started in the morning, when she assumed Marlowe would be at his Main Street office.

“Back, everybody back,” the firemen were saying, pushing the crowd to the opposite side of the street.

They were making no attempt to stop the fire but instead were pouring water on the roofs of neighboring houses, fearing that sparks from the fire would set them alight. More sirens were heard and Lucy realized the call had gone out to neighboring towns for mutual aid.

“What a shame,” Lucy said, to nobody in particular, and a few others murmured in agreement.

Not everyone was sympathetic, however. “Serves the mean old bastard right,” Zach Cunningham said.

“It’s not like he took care of the place,” Sara observed.

“He’s foreclosed on a lot of people,” Lexie Cunningham said. “Now he’ll know what it’s like to lose his home.”

“You said it, man,” Seth said, clapping Zach on the shoulder. “What goes around comes around.” Realizing the crowd was with him, Seth got up on his milk crate. “Burn, baby, burn!” he yelled, raising his fist.

Lucy was shocked, but the crowd picked up the chant. “Burn, baby, burn!” they yelled back. “Burn, baby, burn.”

Disgusted, she tapped Sara on the shoulder, indicating they should leave. Sara, however, shrugged her off and joined the refrain, softly at first but gradually growing louder as she was caught in the excitement of the moment.

Lucy wanted to leave and she wanted Sara to leave, too, but the girl stubbornly ignored her urgings. Finally, realizing she was alone in her sentiments, she shouldered her way through the crowd and headed back to Main Street and the

Pennysaver

office. At the corner, she remembered her job and paused to take a few more pictures for the paper. This would be a front page story, no doubt about it. She was peering through the camera’s viewfinder when the tower fell in a shower of sparks and the crowd gave throat to a celebratory cheer.

Pennysaver

office. At the corner, she remembered her job and paused to take a few more pictures for the paper. This would be a front page story, no doubt about it. She was peering through the camera’s viewfinder when the tower fell in a shower of sparks and the crowd gave throat to a celebratory cheer.

Other books

Mystic Rider by Patricia Rice

Virgin Wanted (BWWM Billionaire Romance) by Cole, Sierra

Alice's Insurrection (Alice Clark Series) by Andrea DiGiglio

The Railroad War by Jesse Taylor Croft

Amigos en las altas esferas by Donna Leon

Hard to Be Good (Hard Ink #3.5) by Laura Kaye

Love Bites by Quinn, Cari

The Viscount's Christmas Temptation by Erica Ridley

Thing of Beauty by Stephen Fried