Christmas Tales of Alabama (14 page)

Read Christmas Tales of Alabama Online

Authors: Kelly Kazek

In 1702, the port city was the first capital of French Louisiana. The year after its establishment as a capital city, some settlers of French descent brought one of their traditions to the city: the celebration of Mardi Gras. The tradition came to America in the late seventeenth century with the first French settlers, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne d'Iberville.

The 1703 celebration was thought to be a small gathering of residents who feasted and drank at Twenty-seven Mile Bluff, which was the first settlement at Mobile.

Over the next century, Mobile would be ruled by the French, then the British and later the Spanish. It became part of the United States of America's Alabama Territory in 1810 and the state of Alabama in 1819. Two decades later, Mobile's place in the history of Mardi Gras, or Carnival, would be solidified when a cotton factor named Michael Krafft unwittingly created the first mystic society in this country, which would become known as krewes when New Orleans began its Mardi Gras celebrations years later. These first celebrations centered on the coming of the new year rather than Fat Tuesday, which stemmed from a French Catholic tradition and is based on the Easter season.

It was New Year's Eve 1830 when Michael Krafft started a tradition. Krafft, who is sometimes described as “one-eyed” and probably had a lazy eye, was born in Bristol, Pennsylvania, in 1807. He had a brother, John Krafft, and a sister, Anne Church Krafft, who would marry Captain Benjamin Vincent, a steamboat captain, and have four children. John and Michael would never marry.

On December 31, Michael and friends Thomas Niles, Robert Roberts, Henry Dagget, Daniel Geary, Nathanial Ledyar, Richard Currie and Amual Kipp celebrated at Antoine La Tourrette's restaurant, located in Southern Hotel in Mobile. As morning broke on the first day of 1831, the drunken men staggered over the cobble-stoned streets of the city of about three thousand people. Through a window, they spied clerks preparing to open Partridge's Hardware Store, stocking rakes and other implements.

The men entered, purchasing cow bells, rakes, gongs and any items that might be used to make noise. Then they paraded through the streets, eventually stopping at the home of Jonathan Stocking, who was elected mayor of Mobile in 1831 and died not long after completing his term in 1834.

That first year, the men called themselves the Midnight Revelers, but when the tradition continued in subsequent years, they would come to be known, in a parody of French society names, as the Cowbellion de Rakin Society. The first mystic society in the country would survive for the next fifty years before others took its place.

Michael, however, would not live to see his group's success. He would move to New Orleans, where many in the group created krewes based on the Mobile societies and organized Mardi Gras there. New Orleans and Mobile were sister cities in many ways. Both were port cities with French origins, and New Orleans later would become the next capital of French Louisiana. Their locations near water would lead to the cities' deadliest commonality: incidence of yellow fever epidemics. Michael Krafft was one of 452 people who died in the epidemic of September 1839. Although he had moved to New Orleans, his tombstone states that he died in Pascagoula, Mississippi.

Despite the fact that more than 26,000 New Orleans residents died of yellow fever between 1839 and 1860, people continued to move to the city, which grew from 70,000 in 1839 to 170,000 in 1860.

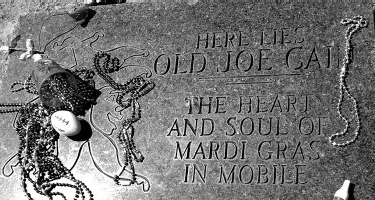

Michael Krafft's body was returned to Mobile for burial in Magnolia Cemetery. The headstone is often decorated with plastic Mardi Gras beads, and his tombstone is etched with the insignia of the Cowbellions: a cow's head, a rake, a hoe and a cow bell. The New Year's Eve parades continued after Michael's death, and Mobile developed a series of events that went into the typical Mardi Gras season in February. Events typically begin in November with balls and parties, and parade season begins three weekends before Mardi Gras.

The Museum of Mobile credits Krafft's Cowbellion de Rakin Society with introducing “throws,” trinkets thrown to the parade crowd, in 1837. At the time, they threw sugar plums, kisses and oranges. In 1840, the year after Michael's death, the Cowbellion de Rakin Society introduced horse-drawn floats into the paradesâthey had previously been pulled by peopleâand an annual theme. The first theme was “Heathen Gods and Goddesses.”

Mardi Gras events in Mobile have only been halted during wartime, particularly during the Civil War. In 1867, Joseph Cain was determined to revive the tradition, despite the occupation of the city by Union troops. Joe, who was married to Elizabeth Alabama Rabby, had helped organize the Tea Drinker's Society before the war. The society held banquets during the New Year's season.

In 1867, when Joe was thirty-five years old, he celebrated Mardi Gras on New Year's by riding in a decorated coal wagon with other Confederate veterans. He took on the fictional persona of a Chickasaw chief he named Slacabamorinico. The choice to wear a makeshift Chickasaw costume was a hidden message to Union troops: the Chickasaw never lost a war to Federal troops.

Joe Cain is credited with reviving Mardi Gras in Mobile following the Civil War. Each year, partygoers celebrate Joe Cain Day by hosting a mock funeral ending at Cain's grave in historic Church Street Cemetery.

Courtesy of Library of Congress and Museum of Mobile

.

For thirteen years, Cain portrayed the fictional chief in annual parades. When he died in 1904, he was initially buried in Bayou Le Batre. In 1966, Mobilian Julian Lee “Judy” Rayford recognized Cain's contribution to the city's history and petitioned to move his remains, along with those of his wife, to Mobile's Church Street Graveyard. The next year, Rayford established Joe Cain Day by organizing a traditional jazz-style funeral procession down Government Street to the cemetery.

Today, Joe Cain Day is celebrated with a procession that can be joined by anyone the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. Also on Joe Cain Day, members of a mystic society formed in 1974 called Cain's Merry Widows dress in funeral attire, complete with veils, and lay a wreath at Cain's grave. There they proceed to wail over the grave and then travel to Joe Cain's house on Augusta Street to toast his memory.

M

OON

P

IE

O

VER

M

OBILE

MoonPies, those chocolaty, marshmallow treats that originate in Chattanooga, Tennessee, are revered by many a southerner, particularly when combined with a Royal Crown cola.

On December 31, 2008, the citizens of Mobile, Alabama, took that reverence to new heights when a six-hundred-pound electronic, lighted MoonPie was raised for the first time to ring in the New Year. An edible version made by creator Chattanooga Bakery, Inc., also was displayed; at the time, it was the world's largest at four feet in diameter, fifty-five pounds and forty-five thousand calories; however, the next year, the bakery outdid itself by displaying an even larger edible MoonPie in Tennessee. Despite their Tennessee roots, MoonPies were chosen as the symbol of Mobile because they are the signature treat of Mardi Gras. Anyone who has watched a Mardi Gras parade in Mobile likely has been struck by a MoonPie tossed by revelers. The tradition of “throws,” as the treats are called, began in 1837 with the Cowbellion de Rakin Society, whose members threw fruit.

Over the years, throws have evolved to include strands of plastic beads, plastic doubloon coins, plastic cups decorated with logos of various societies, candy, stuffed animals, small toys, footballs, Frisbees and whistles. The first MoonPies were thrown by children on the Queen's float in the Comic Cowboys parade in 1956. For a time, small boxes of Cracker Jack also were thrown, but that practice was stopped in 1972 because the boxes injured people on the route. Many accounts state that MoonPies were only chosen to replace boxes of Cracker Jack, but the Museum of Mobile claims that MoonPies came first.

MoonPies were created in the early 1900s when a salesman for Chattanooga Bakery named Earl Mitchell Sr. was visiting a store owned by a coal mining company. When Mitchell asked the miners what kind of treats they would like, they asked for an item that would fit into lunch pails. They also wanted something filling. Legend says a miner held up his hands to show Mitchell how big the snack should be, framing the rising moon. Upon returning to the bakery, Mitchell noticed some of the workers dipping graham cookies into marshmallow and laying them on the windowsill to harden. He decided to add another cookie and coat the confection in chocolate. The miners loved themâand so did everyone else.

Today, MoonPies come in original and mini sizes and in a variety of flavors.

More than four million MoonPies are sold during Mobile's Mardi Gras season, according to Stephen Toomey, owner of Toomey's Mardi Gras Candy Company. Stephen Mussell, one of Mobile's premier Mardi Gras float builders, was assigned the task of building the lighted MoonPie, which is now raised each New Year's Eve, to resemble a banana-flavored pie.

Materials included:

â¢Â  about 1,500 golf ballâsize clear lights;

â¢Â  eight sheets of two- by two-foot-square aluminum tubing;

â¢Â  ten sheets of plywood; and

â¢Â  “massive” amount of banana-colored maché

The edible MoonPie required six pounds of chocolate icing and fourteen pounds of marshmallow.

P

LEASANT

C

RUMP

'

S

L

EGACY

As the year 1951 drew to a close, so too did the life of Pleasant Riggs Crump.

The crisp New Year's Eve air was filled with the sound of Taps to honor the old man, who was the last surviving Civil War soldier in Alabama and is thought by many to have been the last surviving Confederate soldier. Although other men claimed the honor, some of their birth dates have been proven to be false.

Riggs, as he was known, celebrated his 104

th

birthday two days before Christmas 1951. Friends and neighbors, including members of the Talladega Civitan Club, presented him with a cake decorated with 104 candles. Ironically, Crump died in Lincoln, Alabama, a town named for the commander in chief of the Union army, Crump's opponent during the bloody Civil War.

Riggs Crump was born on December 23, 1847, in Crawford's Cove in St. Clair County, Alabama. A month before his seventeenth birthday, he and a friend left home and went to Virginia to enlist in the Tenth Alabama Infantry. From November 1864, he fought until the final day of the war, when he witnessed General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House. Later, he attended Lee's formal surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant before returning home to Alabama.

Many years later, Crump told reporters that he watched Lee, Grant and their staffs approach the McLean House on their horses on the fateful Sunday of the surrender. On April 12, 1865, Crump joined twenty-two thousand Confederate soldiers in the “stacking of arms,” in which they surrendered weapons and flags after marching into town along a road lined on both sides with Union soldiers.

After the war, Crump moved to Lincoln, where he met and married Mary Hall when he was twenty-two. Strangely, Mary, too, would die on New Year's Eve, but forty-nine years before her husband, in 1902.