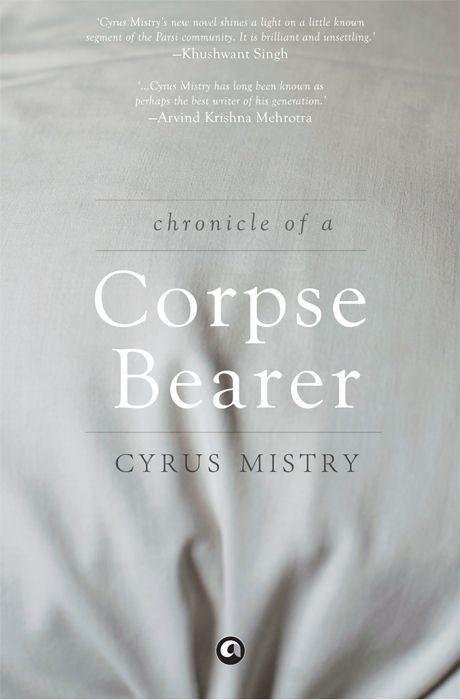

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer

Read Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer Online

Authors: Cyrus Mistry

‘Cyrus Mistry’s new novel shines a light on a little-known segment of the Parsi community. It is brilliant and unsettling.’

—Khushwant Singh

‘Cyrus Mistry’s narration blends measured doses of black humour, irony and tragedy. His characters are real people, and stay with the reader way after the last page has been turned.’

—Robin Shukla,

Afternoon Despatch & Courier

‘

[Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer]

is an unflinching look at the lives of the nussesalars—the dirty little secret of the otherwise admirable Parsi community—which is presented through a combination of heartbreaking candour and occasional ribald Parsi humour.’

—Anvar Alikhan,

India Today

‘Mistry weaves together the all-important topics of love and death in a chimerical, magical world which the reader will remember long after he puts down this book.’

—Ira Trivedi,

The Asian Age

‘Mistry’s pellucid prose, with many a memorable metaphor, makes for delightful reading. What lifts this narrative to greater heights is Mistry’s insight into Elchi’s milieu and mind. Peppered with grey humour, irony and tragedy, this well-crafted book is a winner.’

—Bakhthiar K. Dadbhoy,

Outlook

About the book

At the very edge of its many interlocking worlds, the city of Bombay conceals a near invisible community of Parsi corpse bearers, whose job it is to carry bodies of the deceased to the Towers of Silence. Segregated and shunned from society, often wretchedly poor, theirs is a lot that nobody would willingly espouse. Yet thats exactly what Phiroze Elchidana, son of a revered Parsi priest, does when he falls in love with Sepideh, the daughter of an aging corpse bearer...

Derived from a true story, Cyrus Mistry’s extraordinary new novel is a moving account of tragic love that, at the same time, brings to vivid and unforgettable life the degradation experienced by those who inhabit the unforgiving margins of history.

About the author

Cyrus Mistry

began his writing career as a playwright, freelance journalist, and short story writer. His play

Doongaji House

, written in 1977 when he was twenty-one, has acquired classic status in contemporary Indian theatre in English. One of his short stories was made into a Gujarati feature film. His plays and screenplays have won several awards. His first novel,

The Radiance of Ashes

, was published in 2005.

By the same author:

FICTION

The Radiance of Ashes

PLAYS

Doongaji House

The Legacy of Rage

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

This digital edition published in 2013

First published in India in 2012 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright © Cyrus Mistry 2012

All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to any actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Aleph Book Company. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

e-ISBN: 978-93-82277-85-9

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

For Jill and Rushad

GAP PAA.ORG

GAP PAA.ORG

‘Oi, Elchi, you bloody drunkard! Still lolling in bed?!’

There was no sound more revolting or hateful to the ears than that voice which plucked me rudely from my garden of dreams.

I was under the bower of the giant banyan with Seppy. Of all our numerous hideouts in the forest, this was her favourite. But in that instant, when Buchia’s hideous falsetto impinged on my consciousness, she was gone.

A wretched fatigue hugged every inch of my body like a lover. On my threadbare mattress, I clung to traces of remembered sweetness, longing for more sleep, but knew it would be denied me. . . The flimsy front door of my tenement was being slammed and rattled with an ugly insistence. Presently, the odious shrieking came again:

‘Two minutes is all I’m giving you! Not out by then, straightaway I’m dialling Coyaji’s number. And so much the better if he’s mad for being woken at this hour. . .I’ll tell him everything: fucking corpses have begun to stink, mourners are congregating, but your chief khandhia’s still in bed, pissed out of his skull.’

Abusive harangue, the crunch of footsteps on gravel. . .both receded.

Oh fuck you Buchia, you aren’t paying for our drinks, are you? No time for a sip of water, let alone a tumbler of booze.

Rustom and Bomi would have given anything for a quick stopover last night—all of us deadbeat after walking those six miles to Laal Baag and back with a stiff more corpulent than most—but even simple-minded louts like us know better than to leave a corpse unattended on the pavement while guzzling at an illicit den. So, we hit upon a compromise: resting one end of the bier against a compound wall, Fali’s brainwave this, Bomi ran in and purchased a bottle. Snugly secured between the corpse’s stout legs for the remainder of our jaunt, it had to be pried out with some force once we deposited the body in the washroom of the allotted funeral cottage.

Now how is that any of

your

business, bloody Buchia? Those damn biers we lug around—solid iron—each weighs nearly eighty pounds! And all corpses aren’t emaciated by death, let me tell you. Some positively swell, growing more flaccid by the minute. Besides, how else, I ask you this, how else are the best of us to keep up this carrion work, this constant consanguinity with corpses, without taking a drop or two? The smell of sickness and pus endures; the reek of extinction never leaves the nostril.

Good sport that he is, Fardoon waited until I had knocked back my share of the booze before joining me for the arduous job of washing the man mountain. Fardoon doesn’t drink.

It’s a job that takes courage and strength, believe you me— rubbing the dead man’s forehead, his chest, palms and the soles of his feet with strong-smelling bull’s urine, anointing every orifice of the body with it before dressing him up again in fresh muslins and knotting the sacred thread around his waist. All the while making sure the pile of faggots on the censer breathes easy and the oil lamp stays alive through the night; all this, before we retire ourselves well past midnight. So what’s your fuckin’ fuss about, you bastard of a Buchia?

One side of my head was throbbing, raw; felt a bit of a corpse myself. Then my eyes lit on the wall clock: twenty past six already!

Early morning silence punctuated by a tittering of birds soothed my nerves, but the muscles still ached. . . Outside the wire-meshed window, a sprig of pale orange bougainvillea swayed slightly. As I climbed out of bed, the rays of a fledgling sun touched the treetops lightly with a golden brush. The sky was deep blue and softly luminous, without a speck of cloud. Had I really woken up from dreaming? Or was

this

a dream I was waking to?

How beautiful and peaceful is this place—much of the time, at least—where the faithful consign their dead to the vultures in a final act of charity, their bones pulverized by the sun, then washed away. . .subsumed in the elements.

I grew up not far from here. When I was still a child, I may have been brought along by my parents to attend a funeral or two; but it was only much later I began to see this as my garden, my own private forest: an enchanted place in which I was free to roam, marvelling at leisure at the shapes, smells and colours of nature, the magnificent trees, birds, bushes and all that rocky wilderness.

Near the hill’s summit brood the squat towers—three in number—their jaws open to the sky, allowing birds of prey to descend and eat their fill, then fly up once more, unhindered. Surrounded on every side by a town that grows more noisy and populated by the day, this estate is so vast and secluded that no syllable of human voice or activity grates upon its timbre of peace. Though death is its precise reason for existence, in this garden, life—overwhelmingly—is the victor.