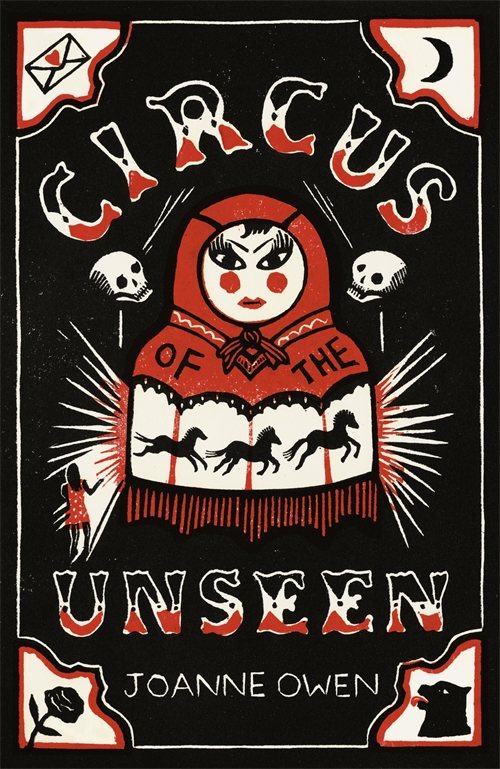

Circus of the Unseen

Read Circus of the Unseen Online

Authors: Joanne Owen

To grandmothers, especially Edith and Thelma, whose tales tell truths

Long ago, when the world was young and people still thought of the marsh and the mists and the witch in the woods, there lived a girl called Vasilisa, whose mother fell gravely ill. On her deathbed, Vasilisa's mother called for her daughter. She took a little wooden doll from beneath her pillow, saying, âWhen I am gone, I shall leave you this doll with my blessing. Promise me you'll always keep her with you, and promise me you'll never show her to another soul. Whenever you need guidance or comfort, give the doll food and she will ease your troubles.' Vasilisa promised her mother all of these things.

When her mother died and Vasilisa felt sick with grief, she gave the doll something to eat, just as her mother had said. Then the doll's eyes shone like two stars and she told Vasilisa to lie down and rest, âFor the morning is wiser than the night.' And when Vasilisa woke, she felt some comfort, as her mother had said she would.

In time, Vasilisa's father, a merchant, sought a new wife, thinking his dear daughter deserved a mother and the companionship of women while he travelled the land doing his work, and he was overjoyed to find a woman who had two daughters of her own. But both the stepmother and stepsisters were jealous of Vasilisa's beauty, and did all they could to make her life miserable. They sent her out to the fields, hoping the sun would burn her skin, and they made her work from sunrise to sundown, hoping she'd turn into a scrawny bag of bones. But each morning Vasilisa fed her doll, sometimes going without food herself, and her doll did her work until everything was done. Her stepmother and stepsisters could not understand why she never burned her skin, or became a bag of bones.

A few years passed like this and, the more tasks Vasilisa was given, the lovelier she became, while jealousy ate away at her stepmother and stepsisters like worms through a corpse. As more years passed and the merchant spent much of his time travelling away from home, his wife sold their house near the town and moved them to a miserable cottage near the forest. And right in the heart of the forest lived an old lady called Baba Yaga, who'd lived away from the world in these woods since the beginning of time. She was in the earth and the marsh, and the mists and the wind. She made the sun and the moon, and the day and the night, and all creatures were her children.

Both her appearance and habits were not of this world. Her body was a skinny bag of bones, and her teeth were like tiny, sharp knives. She flew from one place to another in a giant mortar, paddling her way with a pestle, sweeping away all trace of her path with a broom. Her hut was the only place in the forest where a fire always burned, and she was said to eat children as if they were chickens.

Every day Vasilisa's stepmother sent her deeper into the forest, ever closer to Baba Yaga's hut, saying she needed wood, or berries, or mushrooms that could only be found in its depths, but every day Vasilisa returned unharmed, thanks to the guidance of her mother's doll. As the months passed like this, and spring became summer, and summer slipped towards autumn, the stepmother's anger became so great that she decided it was time to send Vasilisa directly into the jaws of death.

We'd made this journey hundreds of times, maybe thousands. We'd leave the city and turn onto smaller and smaller roads until we snaked through the village and crossed the toytown bridge to Granny's lane. I wound down the window and inhaled the smell of earth and roses, and the marshy riverbank. Those roses and that river meant we were nearly there, which meant having nothing to worry about, and everything to look forward to.

We turned onto the lane and the house came into view. First the ivy-covered walls and the upstairs windows that jutted out like bony eyebrows, then the small wooden cabin perched beside it, with the rocking horse sitting sentry by the door. It was like something from a fairy tale. I tingled. Everything was as it should be. Actually, everything was better than it should be. There was a huge moon resting on the horizon beyond the house. It looked like a massive, milky egg, pulsating with pink and silver, like a heart beating with light instead of blood. It didn't look real. It was special.

A sign

, Granny would say.

Granny was waiting outside. She rushed towards us, smiling and waving her arms. You'd never have known she was so old. She had such soft skin, and her long hair was still autumn-red. From the back, she might have been in her twenties or thirties. She was wearing her favourite spotty green dress, which she claimed to have had since she was eighteen (âThings were made to last back then,' she said), but I noticed she had nothing on her feet, and hoped Mum hadn't seen. She was worried about Granny starting to forget things. I'd seen it a few times myself â like when we'd go to the shop and I had to remind her why we were there, or the time she forgot about the jam and it boiled over and ruined the cooker â but don't we

all

forget things? To me, she didn't seem old enough for us to be properly worried. I mean, with her looking so young, and being so full of life. Still, I'd had to promise Mum I'd look after us both before she'd let me stay on my own for the whole of the Easter holidays.

Granny practically pulled me from the car.

âI can't tell you how happy I am to see my girls,' she said, linking arms with us. âAnd look at the moon! All rosy for my Rosie! Never seen it so fat. What can it mean? It must be a sign for something,' she said, which made me smile. âWill you come in for a cup of tea before you head home, Greta?'

âI'd love to, Mum, but I should get straight back on the road. Look after each other, won't you? No mischief, and not too many late nights.'

âAnd you take care of yourself, my darling.' Granny hugged Mum tight. âI do love you, you know.'

âCourse.' Mum looked surprised, and I was too. I mean, Granny was affectionate, but she and Mum didn't really use the âL' word. âSee you in a couple of weeks.'

âBefore you go, I was wondering if you'd be around tomorrow?' Granny asked. âIn case Rosie needs to call. It is her first time staying without Daisy.'

âI think Rosie's big enough to do just fine on her own, but she can call whenever she wants. See you soon, love.'

I could smell Granny's ginger and coffee cake as soon as I stepped into the hall. One of the things I loved about coming here was that it had always been the same, and it always stayed the same. Same furniture, same smells, same feeling of being warm and content even before you'd sat by the fire or scoffed any cake. Granny took hold of my hands and gave them a squeeze.

âI

have

been looking forward to having you all to myself. I love you both the same, of course, but I think I'm far too old and dotty for Daisy now she's so grown up. Promise me that won't happen to you. Promise you'll always be you.'

Unfortunately, I couldn't promise I wouldn't grow up, but I promised Granny I'd never outgrow her. I knew I could keep that one.

âBut I wouldn't worry about Daisy,' I said. âEveryone's too something or other for her. She's like Goldilocks, except with Daisy nothing's ever just right.'

I was quite pleased with myself for thinking of that, I have to admit, and it made Granny laugh too.

âYou look lovely in that dress,' I told her. âAre we going out somewhere special later? Should I get changed?'

âThank you, Rosie, love, but you don't need a special occasion to look nice, do you?' She smiled. âI've always found that dressing up and looking nice makes

every

day special.'

That was one of the things that made Granny Granny. I mean, she didn't need some big reason to make an effort to look her best. And, actually, it wasn't âmaking an effort' with her. That's just what she did. It was no effort at all. So we stayed in for a special night and made a pot of spicy stew together. My hand slipped with the paprika and I thought I'd ruined it, but Granny said the best ones were supposed to taste fiery. To prove it, she added another spoonful. While it simmered away, we chatted about what we'd been doing since we'd last spoken. I told her I really liked my new English teacher because she let us write our own stories, and that I thought Daisy had a boyfriend, and yes, I was still playing tennis.

âOh, and I've been thinking about auditioning for a play.'

âHow wonderful!' Granny practically whooped. âIt's been a while, hasn't it?'

âDon't get too excited. I'm not sure if I'll actually do it. I mean, I'm probably not good enough.'

âOf course you're good enough, darling. Why wouldn't you get picked? Have some faith. Besides, trying is better than doing nothing.'

âIt didn't go so well last time, did it?'

I still had nightmares about that. I'd frozen on stage about a year ago. Me, the girl who'd been tipped to get a scholarship to a fancy drama school, had crumbled right in front of the director, and everyone else going for the same part. I'd started crying too, and locked myself in the toilet until Mum collected me. Humiliated doesn't get close to how crappy I felt. I fell from Promising Talent to Pathetic Failure in those eternal three minutes I was on that stage, unable to remember a word of my lines and desperate for the ground to gobble me up.

âDon't be scared of yourself, Rosie. Don't be scared of failing and, more importantly, don't be afraid of what you can do. Promise me you'll take the audition.'

âPromise,' I said, hoping I wouldn't have to break it. I knew she was right. I

shouldn't

be scared, but knowing all that didn't stop the doubting and worrying about making a fool of myself again. Then, as I laid the table, I found myself daydreaming about what I should wear to the audition. Granny had a knack for knowing how to get under my skin â in a good way, I mean.

âI haven't had goulash as good as this for years. Decades, even,' she said, and I have to say it was one of the most delicious things I'd ever eaten. âTastes like being bundled up in a big coat around a bonfire, don't you think? All snug and smoky. Exactly how I remember it tasting there.'

âWhere?' I asked, thinking she meant a restaurant we'd been to.

âNowhere,' she said, wiping her hands on her apron. âNowhere important.' But the spark in her eyes told me different.

âWhat's the big deal? Just tell me.'

âPerhaps you won't think it's a big deal. Perhaps you'll think it's a very tiny deal, or nothing of a deal at all.' There it was again, that naughty twinkle. She looked as if she was bursting to tell me something. âI'm not sure I should say anything, Rosie. Your mother will be mad at me. I really shouldn't.' But then she told me her secret, which was that our goulash tasted exactly like the ones she'd eaten in Poland, where she'd lived when she was a young girl.

I had no idea she'd lived anywhere other than here, but I guess she spent so much time asking us about our lives that we never really asked much about hers. As she told me about her time there â learning the language and making friends with people who clearly became like family to her â she sparkled like nothing I'd ever seen in a person, which made me excited too.

âHow long were you there?' I asked.

âNot long enough,' she said, and the spark faded a little. âIt was a dream, Rosie, an absolute dream. The bee's knees. I met my first love there too.' She fell quiet for a moment. Her brow furrowed and she clasped her neck. I'd never seen her look so serious. Then she waggled a hand, as if to wave away her words. âI shouldn't have said anything. Your mother will be furious. It was a lifetime ago, before I had her, before I met Granddad.' She reached for a hunk of bread.

âWhy did you leave?' I asked. âIt sounds like you didn't want to.'

âI had to. My mother â your great-grandmother â was very ill. I was needed at home, back here. What else could I do?' She shrugged. âThen, because of the war, I couldn't return and, by the time it was possible to travel again, I learned that the place had been bombed and there was nothing and no one to go back to.' Her voice wavered.

âSo you didn't

ever

go back?'

âIt was bombed, Rosie. What would I be going back to?'

âBut have you actually checked?' I asked. âMaybe some people did survive. I could help you find out about them if you want. You could go back there. We could go together.' I knew I was getting carried away, but this seemed like something worth getting carried away with. I mean, it was romantic and exciting and

true

. A piece of secret history. âUnless you check, how do you know for sure?'

âI know,' she said. âThe letters stopped coming, there was a newspaper report. It said people left the village, but even they were killed, just as they were about to cross the border into safe territory. Like I said, no survivors. Finish your food. I'm not in the mood for any more interrogation. You can't turn back what's happened. You just have to get on with it. You learn to get used to all kinds of things.'

She suddenly looked so upset, and I felt bad for going on about it. I didn't know what to say to make her feel better, so I did as she asked and finished the goulash. But I couldn't help myself. I'd seen how excited she'd been, and how much these people meant to her.

âPlease tell me something else. I won't say anything to Mum. Promise.'

âYou know more than you think,' she said, provocatively. âLots of stories I've told you came from there.'

That made sense. I mean, she used to tell me and Daisy loads of amazing fairy tales when we were small. âCan't you tell me something else?' I asked. âSomething real?'

âAll tales are real, Rosie. All tales tell truths.'

I smiled. I should have known she'd say something like that. âTell me the tale of the man you fell in love with, then. Tell me the truth about that. What was he like? Was he why you wanted to go back?'

She stood up and straightened her dress, and I saw that her hands were shaking. She had this confused look on her face, like she didn't know what to do with herself, like she was lost.

âThe answer to your question is yes,' she said. âI wanted to go back to him. To him, and the girls.'

I followed her from the kitchen, part of me feeling guilty for pushing her to tell me more and upsetting her, but part of me dying to know more. The living room felt warm with her perfume, and it was much tidier than normal. There were usually piles of books everywhere, and pieces of material for whatever dress she was making strewn over the sofa and armchairs, but everything had been put away, and all the bookcases and ornaments looked freshly dusted. She saw that I'd noticed.

âJust been clearing away the old cobwebs,' she explained. âPutting everything in order. Except things aren't entirely in order. I've lost a necklace. A silver necklace with a charm. Give me a hand going through these drawers, won't you? I really must find it, Rosie.'

We went through every drawer in the desk, every compartment of her sewing box, every pot and vase, but we didn't find it. Granny got down on her hands and knees and started feeling under the furniture. âI have to find it, Rosie. I really do.'

âI'll do that,' I said, and I knelt beside her. I couldn't bear seeing her scrabbling about on the floor like that. She was frantic. âIt has to be somewhere. Why don't you make some tea and I'll look for it?'

âMake some tea? Make some tea?' she snapped. I felt crushed. Granny was never short-tempered. She was never nasty, so I guess that just showed how much she wanted to find this necklace. But she did get up and she did go to make tea and I carried on searching the room. I went through the same drawers again and again. I picked through every box of cotton reels and needles, checked on every shelf and bookcase, but still nothing, so I joined her in the kitchen. She was reading something on a piece of paper at the table. Her hands were trembling as her lips mouthed the words. When she noticed me there, she wiped her cheeks dry.

âDid you find it?'