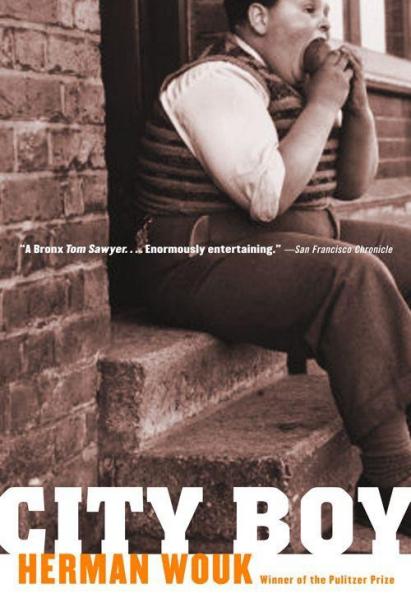

City Boy

Authors: Herman Wouk

Copyright 1948, 1952, © 1969 by Herman Wouk

Copyright © renewed 1975 by Herman Wouk

Preface copyright © 2004 by Herman Wouk

Foreword copyright © renewed 1980 by John P. Marquand Jr.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-07700-2

Contents

ONE:

The First Step in the Mending of a Broken Heart

SEVEN:

The Romance of Art and Natural History

EIGHT:

The Dubbing of General Garbage

TWELVE:

Mr. Gauss's Camp Manitou

FOURTEEN:

The Coming of Clever Sam

SEVENTEEN:

The Victory Speech of Mr. Gauss

TWENTY-TWO:

The Triumph of Herbie

TWENTY-FOUR:

Lennie and Mr. Gauss Take Falls

TWENTY-SEVEN:

The Truth Often Hurts

Novels

Aurora Dawn

City Boy

The Caine Mutiny

Marjorie Morningstar

Youngblood Hawke

Don't Stop the Carnival

The Winds of War

War and Remembrance

Inside, Outside

The Hope

The Glory

A Hole in Texas

Plays

The Traitor

The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial

Nature's Way

Nonfiction

This Is My God

The Will to Live On

This story is dedicated to my motherPREFACE TO THE 2004 EDITION

CITY BOY:

The Adventures of Herbie Bookbinder

C

ity Boy,

my second novel, was published in 1948. I had no reason to think then that the book would survive its season, let alone more than half a century. None of my novels ever had a less promising start.

Just a year earlier, I had entered the American literary frogpond with a noisy splash, and before that I had never published so much as a short story in a magazine. For my livelihood until World War II, I had been a script writer for the great radio comedian Fred Allen. My first novel,

Aurora Dawn,

was a facetious spoof of commercial radio, and the little book caught a publisher's fancy, so he launched it with a blast of ecstatic advertising. In quick obedience to Newton's third law, critics blasted back. All this dazed me. A naval reserve officer, I had written most of

Aurora Dawn

aboard a minesweeper in the South Pacific, to while away boring wartime hours at sea. I did not know enough about the literary world to object to the overblown launching, nor to expect the boisterous counter-attack. It was quite a debut. When the dust settled I had in hand a Book-of-the-Month selection of my first novel, a so-so sale, and a literary reputation demolished before it was built. New authors, fuming over insufficient advertising of their masterpieces, might ponder this true tale.

But there I was, a professional novelist, if a somewhat black-and-blue one. I wrote

City Boy,

and found real delight in the task. To this day the fat little hero, Herbie Bookbinder, remains one of my favorite creations. But my publisher, set back by the critics' onslaught on

Aurora Dawn,

and probably convinced that no novel with Jewish characters could sell anyway—this was gospel back then in the book trade—launched the work as one buries a body at sea.

City Boy

slid off the plank, and with scarcely a ripple went bubbling down. No club selected the book. Nobody bought it. Almost nobody reviewed it. The remainder shops were piled with this novel, while I was still reading scattered out-of-town notices. End of poor Herbie, to all appearances.

Alas! Total disaster with a second book; a very usual thing. Still, I now had a family, and I had come to love the fiction art. I thought I had better have one more shot at the target. I started another novel. My habit was, and still is, to read my work chapter by chapter to a discerning, lovely, but taciturn wife. Once she suddenly remarked, when I was reading aloud an early scene in that story, “If they don't like this one, you had better try some other line of business.” The book was

The Caine Mutiny.

Meantime

Aurora Dawn

and

City Boy

had gone out of print, but I had a new publisher, who liked the books and brought them back to light. That was about forty-five years ago.

Aurora Dawn

remains in print, and the publishing history of

City Boy

since then records successive new editions, translations into several languages, club selections, and usage in school textbooks and anthologies. In the arts, as in most risky walks of life, the good word is

never say die.

My life goal of authorship was fixed when I first read

Tom Sawyer

at eleven, and my working title for

City Boy

was

Tom of the Bronx.

I grew up in a Bronx neighborhood that later became notorious as Fort Apache, but in my boyhood there were idyllic green spaces called “lots,” and more than a trace of the golden light of Hannibal, Missouri, fell on those stony neighborhoods. That glow was what I tried to capture in

City Boy.

Without taking the comparison further, I hope that Herbie and his tantalizing Lucille still come to life in their modest citified way, as Tom and Becky Thatcher will do in Mark Twain's book while the English language lasts.

Herman Wouk

O

n a golden May morning in the sixth year of Calvin Coolidge's presidency, a stout little dark-haired boy named Herbert Bookbinder, dressed in a white shirt, a blue tie and gray knee breeches, sat at a desk in Public School 50 in the Bronx, suffering the pain of a broken heart. On the blackboard before his eyes were words that told a disaster:

Mrs. Mortiner Gorkin

The teacher of Class 7B-1 had just informed her pupils that they must call her “Miss Vernon” no more. Turning to the board with a shy smile, she had written her new name in rounded chalk letters, and had blushed through a minute's tumult of squeals and giggles from the girls and good-natured jeers from the boys. Then Mrs. Gorkin stilled the noise with an upraised hand. She pulled down into view a map of Africa rolled up at the top of the blackboard like a window shade, and the class, refreshed by the brief lawbreaking, listened eagerly to her tale of the resources of the Congo. But Herbert could not rouse himself to an interest in rubber, gold, apes, and ivory; not when the lost Diana Vernon was talking about them. The tones of her voice made him too unhappy.

The anodyne in this boy's life was food. No anguish was so sharp that eating could not allay it. Unfortunately lunch time was half an hour off. His hand groped softly into his desk and rested on a brown paper bag. He felt the familiar outlines of two rolls (today was Monday—lettuce and tomato sandwiches) and an apple. Then his hand encountered something small and oval. With practiced, noiseless fingers he opened the bag, unwrapped some twisted wax paper, and drew out a peeled hardboiled egg. This was a pretty dry morsel without salt and bread and butter, but the boy popped the whole egg into his mouth and chewed it moodily. Like an aspirin, it dulled the pain without improving his spirits. He was aware that his cheeks bulged, but he did not care. Let her catch him! He was her favorite, first on the honor roll, and she could not humiliate him without humiliating herself more. The boy's calculation was correct. Mrs. Gorkin did see him eating, but she ignored it.

In time a beautiful sound rang out—freedom, proclaimed by the clanging of the gong for lunch. At a nod from Mrs. Gorkin, the children who had worrisome mothers ran to a shallow closet and returned to their seats wearing coats, while those who had braved the changeable May weather without coats sat back and gloried in their maturity. A second time the gong sounded. The pupils stood and quietly began to form a double line at the front of the room. Herbie, on his way to the head of the line, passed the teacher's desk. She whispered, “Remain behind, Herbert.” Pretending to have heard nothing, Herbie strolled back to his desk and remained there fussing busily until the class marched out.

A classroom always seems three times larger when the children leave it, and quite bleak. This gives a delicious sense of comradeship to two people left in it together. For months it had been Herbie Bookbinder's good luck to share this sweetness with Miss Diana Vernon after classes. She had detained him for such honorable offices as putting away books, filling inkwells, closing windows with a long hooked pole, and drawing the heavy brown canvas shades; while she combed her long red hair before her closet mirror in the late-afternoon sunlight and chatted with him. It had been magical. Being alone in the room now brought these memories vividly to the boy. When the teacher re-entered the classroom she found her star pupil seated at his desk, his chin resting on his clenched fists, gazing downward at nothing.

The cause of his pain was a slim woman, possibly twenty-seven, with compressed lips, a thin little straight nose, and heavy red hair. She looked, and she was, strict. But she was a woman, and therefore susceptible to male charm, such as inhered in Herbie—and, unfortunately, in Mr. Mortimer Gorkin. The boy glanced at her and felt a pang of self-pity. He could tell by her soft look that she felt sorry for him and wanted to comfort him. Immediately he resolved not to be comforted at any cost.

“Herbie,” she said, walking to her desk and drawing a metal lunch box out of a deep side drawer, “come here and talk to me while I eat.”

The boy rose, walked to the front of the desk, and stood there with morose formality, his arms at his sides.

“Come,” said the teacher, “where's your lunch? Or do you want some of mine?”

“I'm not hungry,” said Herbert Bookbinder, looking away from her to the corner of the blackboard where his name headed a list of three in golden chalk—the honor roll for April. He decided vengefully that he would be last in the class in May.

“It seems to me,” said Mrs. Gorkin, laughing a little, “that you were almost too hungry during the geography lesson—now, weren't you?”

Herbie stood on his constitutional rights and did not testify.

“What's the matter, Herbie, really?” asked the teacher.

“Nothing.”

“Oh, yes, there is.”

“Oh, no, there isn't—

Mrs. Gorkin.

”