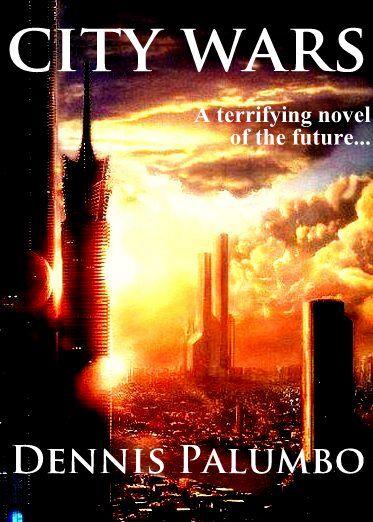

City Wars

Authors: Dennis Palumbo

COUNTDOWN TO DOOMSDAY

Cassandra and Jake survived in the urban wasteland that was Chicago. Waiting in constant readiness for the day when war would break out again … with New York, Washington, perhaps Dallas.

Then the attack came without warning. A limited atomic bombardment that threatened worse devastation.

With the Government of Chicago crippled by panic, betrayal and murder, Jake and Cassandra were forced into action alone.

But if it was too late to save their city, it was not too late to save their love.

City Wars

Dennis Palumbo

STORY MERCHANT BOOKS

BEVERLY HILLS

2012

Copyright © 2012 by Dennis Palumbo. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the author.

Story Merchant Books

Beverly Hills CA 90210

http://www.storymerchant.com/books.html

for my parents

Thrive, cities—bring your freight, bring your shows, ample and sufficient rivers,

Expand, being than which none else is perhaps more spiritual,

Keep your places, objects than which none else is more lasting.

—

Walt Whitman

“We are each of us cities,” the Scholar sang.

George Weston spent the last minute of his life waiting in line at a hot-pretzel stand in the middle of a crowded Chicago intersection. He’d just given his order—two pretzels, hold the mustard—when a cry from somewhere behind him made him look back.

The crowd of people dispersed almost immediately, some shouting and shoving their way off the curb, others merely shrinking back against gray-walled buildings, huddling together and making no sound and looking up at the sky.

George Weston took his lunch and turned away from the vendor’s stand. He squinted in the midday light. Where had his wife gone? She’d been only a few feet away.

He was aware suddenly of the scream of a woman, and, from somewhere a few blocks away, that of a shrill siren.

George Weston finally looked up, just in time to see the dazzling whiteness as it descended.

How absurd, he thought (for he was a man of some irony). How absurd I will look, a smoldering husk with a ruined hot pretzel in each hand.

He’d no more time to reflect on this particular image. The white heat enveloped him now, first searing off his skin, then vaporizing the majority of his internal organs.

He was dead before the thing that had once been George Weston hit the pavement.

A few minutes later, a Chronicler scurried up the walkway, dragging a thick tarpaulin. Wordlessly, he covered the smoking remains; then, taking out his notebook, he filed the death for Census.

The crowd, over its initial fear, ventured closer to the body. Some averted their eyes; most didn’t. A few went so far as to say a prayer. Only one among them seemed near the point of hysterics, a pale gangling woman later identified as Mrs. George Weston.

The Chronicler looked up from his notebook and motioned for the citizens to move on. Then, bundling his cloak of office about him, he disappeared among the shadows and shapes of the dead buildings.

A few blocks away, the siren’s whine grew faint.

Jake Bowman was in a lousy mood. Even tonight, fully tilted on crazydust, with some bills in his pocket and food in his stomach, Bowman found an excuse to look dissatisfied.

“Music’s too loud,” he said, finishing his drink with a long swallow.

His friend Meyerson stroked his beard and grinned, showing the NuPlaz caps he’d blown most of his Service pension on.

“Music’s too goddam loud,” Bowman said again, slamming his open palm on the counter top. The bartender regarded him coolly, shrugged.

Meyerson swung his good leg off the bar stool.

“Why don’t we get a table, Cap? Away from the band.”

He gave Bowman’s sleeve a tug, then hobbled across the crowded room. Bowman took his glass and followed.

His eyes glared through heavy lids. The bar was dim, and his brain seemed dimmer still for the drugs and the anger. He was having trouble keeping the room in focus. Keeping his life in focus.

He took a seat next to Meyerson and leaned back in the chair.

Bowman looked at his friend’s clay-ruddy skin, the points of his eyes, the gray streaks in his beard. Meyerson was a dozen years older than he, and a real warrior, if only half the stories were true. They’d met in a bar much like this one a couple years before, with

Meyerson doing most of the talking. The cobalt had gotten him once, outside of Detroit, and that accounted for the withered leg. Bowman didn’t know what accounted for the rest of him.

“Been down the Center again,” Meyerson was saying. His head was drawn in between his shoulders, and he was trying hard to look conspiratorial. “Doc says maybe next month, Jake. I’ve been savin’ every damn nickel I can, but they practically gotta smuggle the ’Plaz outta them labs, ya know? But Doc says maybe next month. What do ya say to that, eh, Cap?”

“Sounds fine, Phil. Sounds fine.”

“Fine, he says. Jesus Christ!” Meyerson swiveled his head, laughing. “I’m talkin’ about gettin’ hold of a new leg, and he says it sounds fine!”

Bowman was wondering how many customers the bar would hold. The place seemed filled with Urbans, most of them young, many female. He found everything intriguing.

Shouldn’t have blown all that dust

.

Meyerson rapped on the table.

“Hey, Cap, I asked ya a question.”

“What?”

“I said I got a question. How long ya been on this streak?”

“Goin’ for a record, Phil. Four straight nights so far, all piss and vinegar.”

“Christ, you mean you been blowin’ four nights runnin’?”

“I got a bet goin’ with One-Up Hansen. Bastard says I can’t blow a week’s worth.” He grinned. “I say I can.”

“An’ I say you’re gone for sure, Cap.” Meyerson got up from the table, leaned across on thick forearms. Bowman could read the scars. “You listen to me, Cap. You just listen to Meyerson.”

Bowman waved his glass absently, then stared, as though just remembering that it was still empty. He lifted his head, searched through the noisy throng for a waiter.

Meyerson sat down again.

“Look at you, for Christ’s sake, Cap. You’re still a young guy. I’m tellin’ ya, I seen guys—”

Bowman’s head was turned away.

“Shit!” Meyerson kicked back from the table and got back to his feet again. Without another word, he began walking awkwardly toward the exit.

Bowman saw Meyerson’s lumbering form disappear among the dancers clustered on the raised middle floor. He tried to watch them for a while, make the jerky movements of their limbs meaningful against the harsh din from the bandstand. He thought he could hear snatches of conversation from the floor, and the nervous laughter of contacts made; and then there was the music, and all the sounds seemed to come together, to bounce off the floor and the walls and strafe him as he sank his chin into the cushion of his crossed arms on the tabletop.

Strafe him

.

He saw the bodies of the young dancers become the bodies of young soldiers, saw their limbs twitch in the rhythm of their own deaths, saw them flying—

He looked up.

The band was taking a break. He watched them place their instruments carefully on wire racks. The dancers were leaving the floor, heading for tables, for the long dark counter against the far wall.

Bowman tried to remember if he’d been in this place before. The last few nights …

Four. Four nights. Three more to knock off and he’d collect. Three more with the dust burning inside him and giving him tilts, and then One-Up would be counting fivers into his open palm.

Bowman looked at his hands, clenched them into fists. He thought he could hear his veins contracting as blood flowed.

He was tilting. Full tilt.

The pain would come later, and then remembrance.

The warring …

He’d never know what brought him to it, or why it

turned out that he was so good at it. There was the War, and everybody went into the War. But for him it had been different. A discovery.

His talents had not gone unnoticed. While still a relatively young man, Jake Bowman had risen to the highly respected position of Assistant Tactics Coordinator in the Chicago Service. Those had been the glory days, when the fighting was more close-in, when the boundaries had yet to arrive at their present rigidity.

Moving men and machinery for the purpose of achieving a specific goal was what Jake Bowman had lived for, was what had made him whole.

But to keep that wholeness would take more than memories. Which was all Bowman had left.

He glanced at the empty glass on the table before him. Alcohol on top of the crazydust. Stupid bastard!

He ordered another drink.

He didn’t see the whore until she’d sidled up next to him. Bowman’s glance was reflective. The whore was standard bar fare. Beaded designs on her tits. Embedded turquoise. She was totally bald.

“The only crime is inhibition,” the whore said with a smile. “I’ll have a gin and tonic.”

Bowman signaled for the waiter.

The whore sipped at her drink.

“Are you nice?” she said.

“I’m told,” Bowman said. He finished his drink and pushed back his chair.

“Where are you going?” the whore said.

“With you.” He took her by the arm.

The room upstairs was small and warm, womblike, with muted colors and muted sounds filtering through the walls.

The whore sat back on her ankles on the carpeted floor and drew him down to her. Bowman fumbled with the clasp of her robe, cursing under his breath.

The whore reached up behind her and flicked a switch. The room filled with an aromatic mist. Bowman

felt the sting of hundreds of crystalline prickles on his bare chest and arms. Soon he would feel the sting everywhere, and with it the desire, and the will.

He tried to douse it with anger.

“Aphrodisia Clouds are for lunks,” he said between tightened lips.

“Lunks need love, too,” the whore replied, remembering a poster she’d seen once.

Bowman didn’t want to hear about lunks then. Or about love. With the whore beneath him, the stinging mists all about him, Bowman wanted only one thing.

He wanted to get laid.

The crystals turned to drops of silvery liquid and ran in rivulets from his body. He wiped the wetness from his eyes and got up on his elbows.

The whore rolled over beside him, making small sounds. Her hand smoothed the sweat-matted hair on his chest, then drifted to his waist and began tracing circles just below his navel.

Bowman felt as though he’d swallowed his own bitterness. He made his mouth work.

“How much?” he asked, reaching for his trousers.

“You were wrong.” The whore took her hand away. “You’re not nice. Fifty will do.”

“It’ll have to.” He tossed her the bills. “I need the rest to get stoned or drunk, and to find someone to help me decide which.”

“Maybe I’m for sale.”

“Maybe that’s the trouble.”

She sat up, her small breasts jiggling. She noticed the insignia on his belt buckle as he dressed.

“Hey, I know your thing now,” she said. “Why don’t you just find yourself a nice war somewhere and climb down off the dust?”

Bowman thought about hitting her.

Then, thinking again, he walked out of the room.

The Chronicler pulled back his hood and rubbed his eyes. His ledger lay open beside him.

The day had not been uneventful.

The Chronicler undid the bindings of his cloak and began preparing for bed. Like every Urban, he could not be in a room for very long, even one with which he was familiar, without making a judgment as to its size and comfort. Urbans craved space, and he was no exception, though he tried to keep his feelings about such matters in check.

It would not do for a Chronicler to crave very much of anything.

Still, the prospect of advancement pleased him. He sat at his regulation desk, the desire for sleep having passed inexplicably with the donning of his nightrobes, and evaluated his chances. There were many Chroniclers. And so much depended upon mere luck.

He opened the ledger on his desk. The filing had been important, yes; but how much more impressive had it been the only one.

He looked down at the name written in the farthest right-hand column.

George Weston

.

That was the problem. His had been the first death, but unfortunately not the only. The Chronicler sighed, and had he a larynx he might have chuckled at the irony of his own misfortune. Three deaths, three Chroniclers, three separate reports. Just what Census needed. More paperwork.

Of course, these deaths were different. Very different.

He glanced down again at the name in his ledger.

George Weston

No matter how he’d lived his life, Citizen George Weston had achieved his true notoriety in death. He and the other two Urbans. If nothing else, the Chronicler reflected, history would remember them as the cause of Government’s first emergency session since the War.

With practiced ease, the Chronicler bound the ledger in Census-green ’Plaz and affixed the seal of his office.

Then again, he thought as he made his way toward the bedroom, who could say with any certainty exactly what history would choose to remember?

Cassandra Ingram’s lover had been lithe and inventive, and in retrospect ideally cast in the role. He lay now in a tangle of sheets, hair straggling and black on his shoulders. She had remained in the harbor of his arms, ignoring the insistent buzz of the table clock, until duty forced her to rise.

As she padded across the carpet to the bathroom, Cassandra had the fleeting impresson of having walked out of the second-to-last chapter of a bad novel: how to say what had to follow, from what well of sorrow and pain to dredge the necessary tears.

She leaned over the sink and splashed cold water and rubbed at her cheeks.

She looked up. The daily inspection, a ritual that usually brightened her, failed this morning. Cassandra Ingram was one of the few women who truly enjoyed looking at herself; not out of vanity, but rather some unconscious recognition of the rightness of her features—an evaluation that some constants remained just that.

Cassandra was almost tall, with hair dark and thick and often untidy, and deep dark eyes. Of her body she was justly proud: well-formed breasts, high and full; a slender, rounded stomach; near-boyish hips. The night before, her man had called her a fine animal.

She had let the remark pass, as befit her training.

Cassandra heard his moans coming from the next room.

They’d known each other less than eleven hours, she and this man, eight of which they’d spent in bed. But still it would tear at her, the mutual parting, the casual thank-you’s and goodbye’s. The breaking off of things was something she handled badly, and probably always would.

She shrugged and waited.

The man had gone, and she was dressed in the light blue tunic of her Order. She sat sullenly over her second cup of coffee, the early sun hazy through the lattice of her kitchen window.

It was a nice apartment, easily one of the best in the city. She’d had to use her influence to get it, of course,

though few Urbans could have afforded the rent anyway. It had more space than she really needed, but she’d managed to fill the rooms well with things that reflected what she was.

She felt herself frowning.

What

she was. Not

who

she was. For one such as she, they meant the same thing. In most people’s eyes, at any rate. Perhaps in her own as well.

She held the emotion, the irritation, for just a moment. Then her being released it, and it was gone from her thoughts.

She got up from the table and went back into her bedroom. She pulled soft white boots over her bare feet and calves.

Cassandra had been on her current assignment for over a year now, and still it bothered her. As far as she was concerned, Government was made up of crusty old men and women whose decisions had next to nothing to do with her life, and yet hers was the task of guarding one of its highest-ranking members. The job was both unexciting and confining. It also involved adherence to a routine, another sore point with her.

But there was little she could do. Assignments in general were hard to come by, especially in such peaceful times as these. Often she was reminded how grateful she should be that she was working at all.

After securing her apartment, she took the pneumatic down to the garage and signaled for her car. In a matter of minutes, she was entering the Loop.

Traffic was always bad this time of morning, but still she found herself unusually edgy. It was as though the city were charged throughout with a kind of nervous excitement, to which she was acutely attuned.

Chicago was noisy. Diffused sunlight made ambient the gray shadows in which busy Urbans walked and ran and worked. Buildings stood squat and brick-faced, many of them unfinished, piles of raw material often crowding pedestrians off the curb. Very few vehicles were new, of course, and every couple of blocks a stalled car brought the already-slow procession to a halt.

Cassandra braked at yet another blocked intersection.

She hadn’t tinted the visors of her Government vehicle; and though it was unmarked, a few passing citizens could still spy her through the glass. Often they’d point. It was something else she’d have to grow used to.