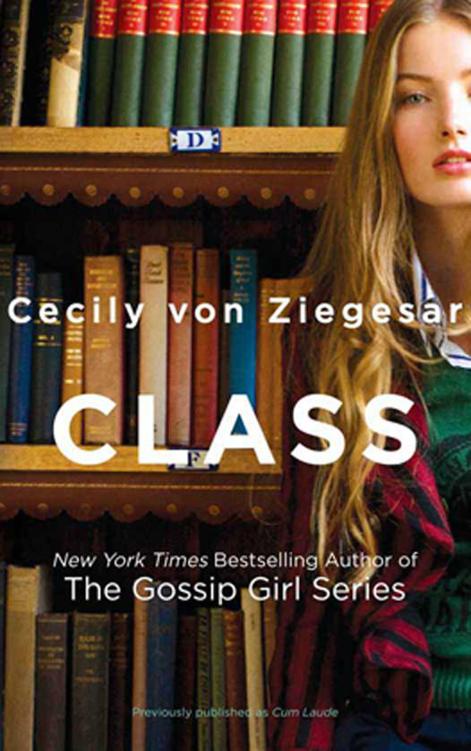

Class

Authors: Cecily von Ziegesar

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #College Freshmen, #Young Adult Fiction, #Wealth, #Juvenile Fiction, #New York (N.Y.), #Crimes Against, #United States, #Women College Students, #Interpersonal Relations, #Coming of Age, #Children of the Rich, #Boarding Schools, #Community and College, #Women College Students - Crimes Against, #People & Places, #Education, #School & Education, #Maine

Class

Cecily von Ziegesar

Previously published as

Cum Laude

For my teachers

Considering the lack of direction in the world, it seems as though many people get through college and beyond without really questioning who they are.

—Preface,

The Insider’s Guide to the Colleges,

1992

Contents

College is for lovers. At least, this one was. Looming…

The relationship between town and college is often fraught with…

It’s often said that the best way to strengthen a…

The sheep were out grazing and the house was quiet.

College has a break-in period. First there is the unfamiliar…

Dexter was an earnest place. Eliza had been waiting all…

And so it went. Shipley lost her virginity to Tom…

At college you are free to do as you please,…

November was a curious month. Some days it was warm…

Why take the job when she didn’t need the money?

In driver’s ed they teach you that most accidents happen…

Tuesday was Election Day. The more conscientious students hurried back…

Nick lost his zen the hard way. It was taken…

Holidays are a state of mind. You spend all day…

December came, and it was as if Thanksgiving had never…

Even the most bucolic college suffers from bouts of nerves,…

Second best to earning a lot of money and spending…

The sun had set at five o’clock and the air…

The average freshman course load at a liberal arts college…

They say a pet can do wonders for your mental…

The dorms were alive again. Everyone had returned from the…

It wasn’t that long ago that Nick had waited outside…

Sleep and wakefulness are active states controlled by specific groups…

C

ollege is for lovers. At least, this one was. Looming up out of the trees on its hilly pedestal, Dexter College looked so strikingly pretty and at the same time so quaintly academic, it was almost as out of place in its rural setting as some of its students. The campus was fortified on all sides by forests of ancient conifers, tall birches, and dense maples, so that only the proud white spire of the college chapel was visible from town. Homeward Avenue, the road that led uphill to campus from Interstate 95, continued down the hill to the blink-and-you’d-miss-it town of Home, Maine, which consisted of a Walmart, a Shop ’n Save, the Rod and Gun Club, and a few mom-and-pop shops frequented only by locals.

Shipley Gilbert would have sprinted up the hill to campus if she could, but her family’s Mercedes was loaded down with a semester’s worth of freshman essentials, so she had to drive. At least her mother wasn’t with her. Shipley had insisted on that.

She steered the car into one of the temporary parking spots in front of an imposing brick building with the word “Coke”

engraved in marble over its black double doors. The parking area was a busy place. Students carted wheeled suitcases and cardboard boxes, dads reined back dogs on leashes, little sisters twirled their skirts, little brothers shot at birds with their fingers cocked, moms fanned the humid air. The sky was blue, the grass green and freshly shorn, the brick red and clean. A gaggle of tie-dyed T-shirted boys played Hacky Sack on the sprawling lawn. A handsome young English professor sat cross-legged as he read aloud from Walt Whitman’s

Leaves of Grass,

trying to inspire a thirst for something other than beer in the twitching semicircle of incoming freshmen seated around him. Three girls in matching pink Dexter T-shirts jogged toward the field house.

Dexter College was exactly as advertised.

Shipley stepped out of the car, releasing the scent of Camel cigarettes and Juicy Fruit gum into the sun-burnished air. Never a gum chewer or a smoker, she’d decided to cultivate both habits on the drive up. A late August wind rustled the maple trees that stood between the car and the quad—that long expanse of grass at the center of Dexter’s campus. On either side of the quad, redbrick buildings with massive white columns challenged each other to do better. The pristine white clapboard chapel stood at the peak of the hill at one end of the quad, and Dexter’s new glass and pink stucco Student Union stood at the other end, a perfect juxtaposition of tradition and modernity.

“Tradition and Modernity” was the college’s most recent motto, indoctrinated during the Student Union’s ribbon-cutting in June. The Dexter College bookstore even sold a pair of wind chimes with the word “Tradition” printed on one bulky brass chime and “Modernity” on its slim stainless steel mate. Of course the Dexter College letterhead still bore its original Latin motto—

Inveni te ipsum

(“Find yourself”)—but very few students knew or bothered to find out what it meant.

Shipley inhaled the clean country air and imagined kicking up the maple leaves this fall when they were red and crisp and covered the ground. Bundled into her favorite cream-colored cable-knit sweater, she’d stroll along the stone walks with a group of new friends, drinking hazelnut-flavored coffee from the Starbucks café, discussing poetry and art and cross-country skiing, or whatever people talked about in Maine. Eager to get on with it, she popped open the trunk and grabbed the handles of her largest duffel bag.

“Want some help?” Two boys appeared at her sides, flashing eager, helpful smiles.

“I’m Sebastian.” The taller of the two reached for the duffel bag and then ducked into the car for another. “Everyone calls me Sea Bass.” He tossed the second bag at his friend, whose dense thicket of hair could only be described as a Greek afro. “That’s Damascus.”

Damascus clasped the duffel against his burly chest. His knuckles were meaty and tan. “We’re totally harmless,” he assured her with a mischievous smile.

Shipley hesitated. “I’m on the third floor. Room 304. I guess that’s kind of a hike?”

“Fucking A!” Sea Bass crowed, the corners of his mouth spreading so wide they nearly touched the tips of his carefully sculpted sideburns. “That’s right next to us!” He dropped Shipley’s bag on the ground and threw his arms around her, hugging her with such force that her feet left the ground. “Welcome to the first day of the rest of your life!”

Shipley took a startled step backward and tucked her long blond hair behind her ears, blushing furiously. She wasn’t used to being hugged by friendly, boisterous boys. She’d gone to the same girls school—Greenwich Academy—since kindergarten. It had a brother school—Brunswick—and she’d sung in choir

with boys and even had a male lab partner in AP Chemistry. But because her father was of the mostly absent variety and her older brother was strange and remote and had been away at boarding school almost since she could remember, she remained unsure of herself around boys. She walked around the car and opened the door to the backseat, where she’d stowed her goose down pillow and her portable CD player, wondering if she would take to fraternizing with males as easily as she had taken to chewing gum and smoking.

“Okay.” She tucked the pillow beneath her arm and slammed the door closed. “I’m ready.”

“So why’d you choose Dexter?” Sea Bass asked as she followed him up Coke’s dark and winding back stairs.

Shipley shrugged her shoulders. “I don’t know,” she answered vaguely. “My brother went here.” She paused. “And I didn’t get into Dartmouth.”

“Me neither,” Damascus replied from behind her. “I guess that’s why we all end up here, huh?”

Shipley followed Sea Bass down the hallway. Dexter provided a dry-erase board on the door of each room so that students could leave messages for one another. Yesterday, the staff from the Office of Student Housing and Campus Life had marked each board with the names of the students who would occupy each room. The names “Eliza Cheney” and “Shipley Gilbert” were written in loopy cursive on the board outside room 304.

The room itself was small and plain, with two single wooden beds pushed up against the white walls. A wide wooden desk stood in front of the only window, with a chair on either side and a lamp in the middle. Across from the desk stood a built-in set of drawers with a large rectangular mirror and an electrical outlet for a hair dryer or curling iron on the wall above it. The drawers were framed by two shallow, rectangular spaces fitted with

wooden rails for hanging clothes. The white walls were freshly painted, but the wooden furniture and orange linoleum floor were scratched and pen-marked, bestowing the room with a gloomy institutional charm.

Shipley sat down, claiming the bed nearest the door. Sea Bass and Damascus hovered in the doorway.

“You want beer?” Sea Bass asked. “We ordered a keg.”

“Funnels!” Damascus whooped.

Down the hallway Shipley could hear the sounds of parents calling out their last good-byes. “Don’t we have to leave for orientation soon?” she asked.

Freshman orientation was a Dexter tradition. Incoming students spent a night camping in the woods with their roommate and five or six other freshmen, under the guidance of one of the professors.

“Nah.” Damascus ran his hands over his chubby stomach. “We’re juniors. Been there, done that. We just got here early to party. Hardy.”

Sea Bass went over and pushed open the window as far as it would go. He perched on the window ledge, stretching his long legs out in front of him. The knees of his jeans were split open like giant paper cuts. “They give all the freshmen the tiniest, shittiest rooms. Ours is like a palace compared to this.” He watched as Shipley fluffed up her pillow and tossed it onto her mattress. “So what class was your brother in?”

Shipley hadn’t given any thought to how she’d respond to such a question. Four years ago, she’d come with her parents to drop Patrick off at this very dorm, in a single room on the first floor. He’d sat on his bed with his jacket on, his carefully packed trunk at his feet, and waved them cheerfully away. Two months later, the college had called to complain that Patrick rarely went to class and often left campus for days. A month after that, they’d

called to say he’d disappeared entirely, leaving behind his unpacked trunk.

Traces of Patrick appeared on credit card bills. He’d been to bars, motels, and diners all over Maine. Then there were the police reports. He’d broken into empty houses to get warm and slept in parking lots, campgrounds, and on beaches. He’d stolen a brand-new bicycle. Then there were the emergency room bills. He’d had pneumonia, frostbite, and poison ivy.

Shipley’s parents tried to leave word for him to come home or at least call, but he never did. Long after dinner was over and Shipley had wandered up to her room to finish her homework, they would sit at the dining room table, drinking in silence. Sometimes her mother cried. Once, her father broke a plate. Eventually they canceled Patrick’s credit card and gave him up for lost.