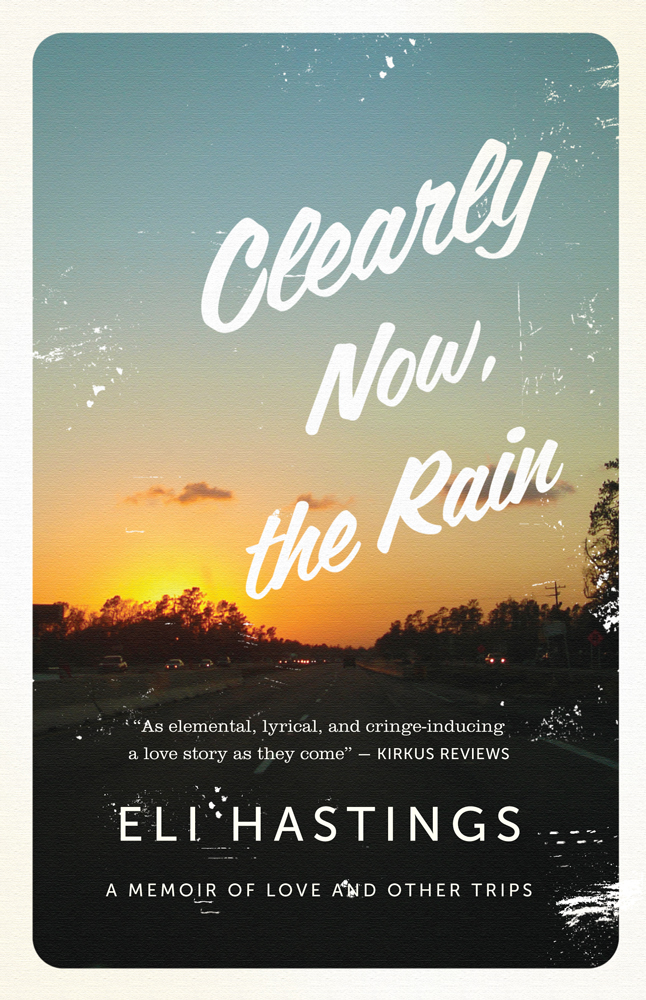

Clearly Now, the Rain

Read Clearly Now, the Rain Online

Authors: Eli Hastings

For her, of course. And for the rest of us.

Prologue

My truck is stalled in the middle of a skinny one-way street in the University District. Rain slides down the windshield and distorts the gray world outside. My fingers are wrapped around the steering wheel, knives and clubs on the floorboards. Hugh is as taut as a stretched bungee cord at my side. The ripping of traffic in the rain comes from Forty-fifth. Luke answers his phone in the backseat.

Get

out guys,

he says.

Get out of the car

. And there are so many things, so many possible pieces rolling up from the back of my mind, and we're out of the truck and Hugh is shaking, more scared than I've ever seen him, and my hands can't hold the keys so I put them away. Luke clutches a raspberry smoothie with one hand, holds the cell to his head with the other, marching back and forth in front of the truck, listening, waiting, for what we don't know because he won't look at us, won't answer the broken whisper every few seconds.

What's going on? Who is it?

And the rain comes down harder, the mist gets thicker, and commuters stare at us as if we are ghosts.

Part One

One

We'd been fired into America like pinballs. We were joyous young clichés, Louis and I, with our jointly owned VW van, Kerouac stories, and bags of drugs. We'd only become close in the last year and we were a strange pair: Louis near six feet, broad shoulders, black hair shorn mostly off then; I was short, skinny, blond hair growing into impossible tangles which, to my eternal mortification, I'd later try to pass off as dreadlocks. He carried the love of many people because of the high school years of designated driving, generosity, the shoulder he offered for adolescent crises. In short, he was full of humor and kindness and I was intense, rather self-absorbed and embittered. But we sensed the space our friendship had to grow into and the will to

go

was something we shared in that spring of 1996.

There were a lot of elements that went into my momentum away from Seattle then. Only two months after we tossed our tasseled caps, Louis and I had moved into a newly constructed, spacious five-bedroom with three other high school friends, courtesy of a crooked realtor who demanded cash and no rental contract. The scenario was, at first, the culmination of a dream we'd all shared for years: no more classes, no more books, no more busywork and what passed for education at our inner city high school. We all got service sector jobs and pooled our money for discount groceries and beer, believing giddily for a time that we were crafting an adult community from the ranks we all considered as close as family. But the dreams of high school die hard and the mismatched workaday schedules, the filth multiplied by five adolescent males, and the pressures of bills came together with considerable speedâas fast as we'd alienated our entire residential block with parties and late night dramas on the back porch.

One January night Louis and I lounged in his back bedroom, the drapes pulled against the nastiness of the winter; I recall waterlogged leaves splatting against the pane in the wind like wet rags. A drunk stranger weaved past Louis's open door, presumably looking for the bathroom. I shoved it closed and turned Bob Marley up on the stereo, sliding a glance at Louis who, for the first time I could recall, was scowling along with me. In the soupy light of the candles and the far-away optimism of the reggae, we both silently discovered in that moment that this communal party life was not what we'd dreamed. It was no kind of destination and, at least for now, in the middle of that dead, freezing post-high school season, Seattle had become a husk and we had to empty our bank accounts and try a more extreme version of freedom: a road trip with no destination.

I'd also left behind a disturbed friend. There had been a fissure running through him for years, and in the last months it had finally yawned wide, becoming full-fledged schizophrenia. This development brutally erased any hope I'd harbored of helping him. Getting physically distant was a partial balm to my guilt, disappointment and fear, conjured forth by a very rough ride at his side.

My brief experience with corporate America, as an espresso jerk in the financial district, was another element that caused me to walk away from my familiar life with a straight spine. They had rules, which now seem a reasonable part of customer service but then caused me great consternation: you had to “strike up chat!” with and smile at every single customer who came through the door. That little shop hosted some angry and sad moments: when they 86'd the Professor, a sweet and silent homeless man who voluntarily swept our sidewalks, because a banker complained about his smell. It was not a context in which I fit and the impulse to untie the apron and fling it down in protest grew acute quickly.

My most vivid memory from that job is the phone call: I was in the midst of the mid-afternoon rush, whirling from the espresso machine to the garbage can with a steel tub of scalding coffee grounds in hand when the phone rang. The apple-faced manager said with bright annoyance that it was for me (we weren't supposed to receive social calls at work, needless to say). I dumped the grounds, absorbed the pointed sighs of the waiting businessmen, hooked the phone under my chin and learned that one of my best friends, Hugh, had just lost his big brotherâa role model to us allâto suicide in his parents' home.

These were some of the events that sent me off bitterly into America, to be as naïve and recklessly free as possible until college began in the fall. I believed I deserved it, as if it were my only chance, as if I weren't on the track to a private liberal arts school and a life of sampling experience, of the luxury to explore.

With these blinders on, with this momentum, I traveled toward Serala for the first time.

One of my and Louis's first stops was Sage Hill, the small college we would enter six months later. Our friend Jay had already started there, straight out of our ghetto high school. By the time Louis and I made it down to visit that corner of Riverside county, beneath the brown air and hard sunlight of the desert, Jay was already deeply in love with Serala.

Jay wasn't the type to flip easily over a girl. I'd known him since the seventh grade when he'd a been an intellectual band geek, his passion and authority on many subjects so grown-up that it used to dumb most adolescents into silenceâthose whom it didn't grew comfortable in Jay's orbit. In the eighth grade we'd been urged into an extracurricular debate class together and I'd come to appreciate Jay, and to see that his bombastâalways impressive, not always welcomeâarose from insecurity. One thing he'd always had, though, was a funky and intimate relationship with rhythm, and he graced the high school jazz band, and, in college, both punk rock and hip hop crews with leadman presence. He had thinned and refined into an oddly handsome and sophisticated cat by the time he met Serala.

Man, I don't know how to tell you, I'm really trippin' over this girl,

he'd reported to me late nights on his dorm phone that winter, blowing smoke out in frustration.

There's no way for me to say what it is she does to me. She's hard but so goodâlike drugs almost. But she loves different.

The first time I saw her, I was scared of her. I wonder if it showed.

She is sitting in the corner of a cinderblock dorm room. She smokes furiouslyânot fast, but with drags that seem lethal. She is silent and her eyes are purple, bagged, like they've weathered a storm. Her south Indian skin is as dark as her pupils. She watches us severely. I try to tell myself that she is clearly a hamper on the good times we've planned with Jay, and that I don't give a shit what she thinks. But these falsities evaporate every time I feel her aloof gaze hit me.

Soon the silver dollar sun is halfway dropped, shadows are growing and someone has produced malt liquor. We are in a dorm room next to Jay's that has been abandoned in typical private college fashion: the administration has not even noticed that spoiled teenagers are turning it into a den of vice. Someone scrawls a quote on the wall and I follow the lead. I rise with drunken steadiness in the dying sunlight that leaks in from the window over Serala's shoulder, and slash a large RIP for Hugh's brother across the east wall. I tell myself I'm eulogizing my dead classmate, but I'm also thinking that this might gain me Serala's attention. And it works: within moments, she touches me for the first timeâgives up her drawn pose on the desk chair, eases near and puts a cool palm on my neck. She tells me with that touch that I am allowed in. I feel my good fortune open in my chest.

During those days that Louis and I lingered at Sage Hill I remember her picking up every expense and warning off our protests with glares. Jay was walking on clouds. I suspect she could have gotten him to drive her to Tijuana for an ice cream cone if she desired, but she wasn't like the game master girls of high school, collecting favors, gifts, and affection for sport. She didn't seem to be asking anyone for anythingâexcept sometimes to leave her alone for a bit.

Jay would speak of her urgently, always shaking his head as he did so, as if he only half-understood this person and what she was doing to him. He could be honest about this with me because he had years of trust and comfort to draw on; in her presence he was more outwardly confident and more aggressively charming than ever.

She drives me fuckin' nuts, man,

he'd say, and sometimes I could glimpse the fear alongside the love, the thin line that ran through his heart. A preview of storms to come.

There is one picture of her that rises above the blur: in the institutional laundry room of the dormitory, white cinderblocks and white washing machines and her, sitting halfway inside one of the dryers, where someone had tossed her, skinny limbs spidering out, dark as a shadow sweeping the desert against all that white. She's giving the camera a look of pure defiance, daring the viewer to chuckle, restraining her own laughter, as if this tomfoolery were serious business, her middle finger raised.

When we got restless, Louis and I climbed into the VW van and hit it.

We stood beneath the thousand-foot walls of Zion National Park; we rolled through its snaking byways, beating drums on the dash to Marley and De La Soul. We completed ill-advised scrambles around the Grand Canyon. We made it to the smack-dab center of America, where we lodged ourselves with an old filmmaker and weathered a Kansas twister. Then it was south, to the heavy-aired magic of New Orleans and the madness of Jazz Fest. Then further, to Georgia, where we abused the wealth and generosity of my relatives, borrowing BMWs and pushing them down freeways with the fire of good whisky. We hiked in the magic light of the Smokies. We rambled to Providence where we lived with wild artists and the days filled with basketball games on sticky courts deep into the spring. In West Philly we got lost and came face-to-face with local thugs who decided to let us pass with only cold glares and the flash of a pistol. Then to Boston, in and out of close and not-so-close friends' lives, gobbling up hospitality as quickly as the ounces of weed we'd mailed ahead of ourselves.

Jay had found his way to a plane ticket to join us for a spell, motoring the East Coast. It wasn't till we scooped him at Hartford International that we learned we were expected at Serala's house that nightâbefore Serala herself would fly in from L.A. twenty-four hours later.

I recall nearly swallowing my tongue at her mother's beauty. The confident way she swings her green eyes around is so similar to her daughter but without the edge. She piles us into the leather interior of her Lexus and takes us to feast at McDonald's.

The next morning her mother drives us into New York City and, en route, does no less than the following: smokes skinny cigarettes, drinks coffee, converses with us, opens and closes files on her laptop, cuts off several drivers, talks on her cell phone, and yells at a traffic cop who, in her estimation, is doing a poor job. Us Seattle boys clutch door handles and do our best to impress her with our wit and intellect, both dampened by the driving experience and a great deal of weed.

In all the years that came after, me sitting shotgun beside Serala, I never mentioned the driving traits she'd inherited; I just fastened my seatbelt and smiled. But I did consider that having a mother with that much poise and bearing must have prescribed her a durable veneer, right from the beginning.

And so Serala arrives that evening, looking poorly rested and nervous at the fact of home. That night we slouch around a booth in a diner. Jay is doing what Jay does when he wants to impress: monopolizing the floor, talking and talking to demonstrate his knowledge of sundry subjects. Louis is doing what Louis does well, too: nodding Jay along, laughing, inserting jokes, helping him carry the burn of the limelight.

But I don't mind just watching Serala smoke and drink coffee and Coke, alternating sips. Once in a while, when my eyes are on the ribbons of taillights outside the window, I feel her gaze land on me. When she leans over to her friend Cassie with a long ash on her cigarette and mischief in her eyes, and whispers in her ear, I strain to hear but cannot except for the effusions that they want us to hear, the flirty, showboat phrases suddenly shouted (we were still teenagers after all):

no way! I did

not

say that! Fuck you, you're one to talk. Cassie, you better notâshut up!

Later, walking down a street near her house, Serala wordlessly takes my hand in hers and holds it tight until we get to our destination: a lit-up court where we play drunken tennis with our hands.

After that Louis and I made another huge loop in the center of America and, cruising a Colorado highway with a bottle of honey wine one July day, we decided to drive home. After three months, some twenty-six states, seventeen thousand miles, and countless adventures and mishaps, all that was left was one more ribbon of highway. I had gained more than what the wild sociology of the American road had afforded me; I had gained the caliber of friend that would be by my side in many unforeseeable journeys down the line. Louis carried his love like his bass guitarâslung easily and comfortably over his shoulder, less forgotten then grown into. While I'd spit all my hurt and rage about my parents and stepparents, about my crazy ex-best friend, about Hugh's brother, about ex-girlfriends, Louis nodded, slapped my shoulder, rolled another joint, switched the tape.

When I see Serala again in the parking lot of Jay's place in Seattle in mid-August, I find her face altered, and not merely by the hoop through her lip. The usually flawless skin beneath her eyes is raw and her lip quivers. I've learned that Jay slipped up and cheated on her and, now, this has left her unmade for the stage of the world. She slides a tissue-wrapped knuckle across her cheekbones. It leaps off my tongue:

I'm sorry about what happened; I think it's fucked up.

I feel awkward, standing there, trembling a little in my flip-flops and ragged shorts. But when she pitches her Pall Mall, blows out the last plume, stands and looks me in the eyes, kisses my cheek and wraps skinny arms around me, I feel like I would kill for her.