Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (11 page)

Read Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Egypt, #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State

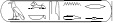

Again, however, we have to be careful when approaching Cleopatra’s Egyptian art. Cleopatra has long been recognised as a brand name, with strong selling power, and canny antiquities dealers have found it all too easy to add a cartouche to an insignificant ancient

statue, instantly tripling its value. As a result, many of the ‘Cleopatras’ that made their way into western collections during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are now recognised (recognised, often, by their ill-written and badly copied hieroglyphs) as forgeries. Cleopatra’s genuine Egyptian-style three-dimensional images are all relatively small; we do not have any colossal Cleopatras, although the ongoing reclamation of Ptolemaic statuary from the sea at Alexandria offers a glimmer of hope that one day this situation might change. In the meantime, it seems likely that all her surviving statues are cult images, manufactured for the temples and shrines dedicated to her personal cult. They show Cleopatra as a healthy woman in the prime of life; again, this to be expected. Women rarely grow old in Egyptian art.

26

Although conforming to the same general pattern, the statues show a degree of flexibility and individuality; the overall appearance is typically Egyptian, with traditional postures, wigs and clothing, but Hellenistic accessories occasionally appear, there are classical noses and eyes, and we can sometimes glimpse Hellenistic curls beneath the formal Egyptian wigs.

The best example of this art style is a black basalt statue of unknown provenance, now housed in the Hermitage, St Petersburg. It shows a young queen standing tall and slender against a back pillar, her left foot slightly advanced. Her tight linen sheath dress – impossible to walk in without the benefit of Lycra – clings to the curves of her breasts, stomach, hips and thighs. Her navel is a dimple beneath the fine cloth. In her right hand she holds the

ankh

, the Egyptian symbol of life; on her head she wears a heavy tripartite wig (a wig which divides into three parts; one falling on each side of the face and one falling behind). She wears the triple uraeus (triple snake) on her brow. Her oval face has the prominent ears and exaggerated almond-shaped eyes seen in earlier Ptolemaic statuary. Her mouth turns downwards and her chin is square. The only dissonant note is the double cornucopia that she carries in the left hand. For the cornucopia, or horn of

plenty, is a Greek symbol. Firmly associated with queens, it first appears in Egyptian royal art during the reign of Ptolemy II, when it is added to images of the deified Arsinoë II. This statue is unlabelled and, on the basis of the double cornucopia, was for a long time identified as Arsinoë II. But Cleopatra, too, favours the cornucopia, and the presence of the unusual triple uraeus strongly suggests that this is a representation of Cleopatra VII.

The uraeus is the rearing cobra worn on the forehead by kings and queens from the Old Kingdom onwards. Wadjyt, ‘The Green One’, the snake goddess of Lower Egypt and the Nile Delta, decorates and protects the royal crown and its wearer. To understand the symbolism of the uraeus, we need to understand the ancient creation myth told by the priests of the sun god Re at Heliopolis. This explains how the first god, Atum, lived on the island of creation with his twin children, Shu and Tefnut. One terrible day Atum’s children fell into the sea of chaos surrounding the island. Devastated, Atum sent his Eye (a form of the goddess Hathor) to search for his missing children. But when the Eye returned with the children she found that the sun had replaced her. Enraged by this betrayal, she transformed herself into a cobra, and Atum, first king of Egypt, placed her on his brow.

Most of Egypt’s dynastic queens wore a single or a double uraeus on the brow. Many also wore the short

modius

or platform crown, surrounded by multiple uraei and often topped by a more elaborate crown. But the triple uraeus – three cobras worn on the brow – is rare and has, in recent years, come to be associated with Cleopatra VII.

27

The symbolism of the three snakes is difficult to assess. It may be that the triple uraeus is to be read as a rebus – a visual pun – that translates from Ptolemaic Egyptian as either ‘queen of kings’ or ‘goddess of goddesses’. Alternatively, it could represent three individuals: Isis, Osiris and Horus perhaps, or a queen’s triple title of king’s daughter, king’s sister and king’s wife.

28

It may even be a simple misunderstanding of

dynastic symbolism, with the more traditional double uraeus plus central vulture head worn on the brow by earlier queens being transformed into three snakes by the Ptolemaic artists.

The use of the triple uraeus as a diagnostic tool to identify otherwise unidentifiable Cleopatra images remains contentious. A limestone crown, part of a broken statue recovered from the temple of Geb at Koptos and now in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London, is a good example of this type of reasoning. The inscription recorded on the crown refers to a ‘hereditary noble, great of praise, mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt, contented … king’s daughter, king’s sister, great royal wife who satisfies the heart of Horus’, but omits to name names. The crown, which is made up of double plumes (two tall feathers associated with the cult of the Theban god Amen), a sun disc (associated with solar cults), cow horns (associated with the goddesses Hathor and Isis) and triple uraeus, was originally identified as belonging to a statue of Arsinoë II, who is known to have been active in this region; the Koptos Isis temple was associated with the Iseion at the central northern Delta site of Behbeit el-Haga, which was patronised by her husband Ptolemy II. But Arsinoë tends to wear her own, specific crown and, as Cleopatra is now strongly associated with the triple uraeus, historians have started to wonder whether the anonymous husband could be either Ptolemy XIII or his brother Ptolemy XIV. Similarly, a pale blue glass intaglio with a portrait of a Ptolemaic woman of unknown provenance (now in the British Museum) is identified as Cleopatra on the basis of the hairstyle, broad diadem and a peculiarly prominent triple uraeus, which virtually sits on top of the queen’s head.

Just one sculpted ‘Cleopatra’ appears to straddle the gulf between the Hellenistic and Egyptian art styles. A Parian marble head, recovered from the wall of the Church of San Pietro e Marcellino in the Via Labicana, not far from the sanctuary of Isis in Rome, is today housed in the Capitoline Museum. The head was originally part of a

composite statue. It has no Egyptian-style back pillar, yet the face is unmistakably Egyptian in appearance. The head wears a tripartite wig and a vulture crown or headdress. This headdress, as its name suggests, has the appearance of a limp bird draped over the head, with the wings falling either side of the face, the tail hanging down the back and the vulture’s head and neck rising from the wearer’s forehead. In this case the vulture’s delicate head has been lost, as have the queen’s inlaid eyes and the tall crown that she originally wore on top of her headdress. The vulture headdress was originally worn by Nekhbet, goddess of southern Egypt and, in some tales, mother of the king. Other goddesses subsequently adopted it, as did dynastic queens; the earliest example of a vulture headdress, worn by a now-anonymous queen, comes from Giza and dates to the 4th Dynasty. Nekhbet’s northern counterpart, the snake goddess Wadjyt, introduced a variant by replacing the bird’s head with a snake; as vultures and snakes were regarded as good mothers, this modified vulture headdress emphasised the link between queens and motherhood. By the Ptolemaic age the headdress had become closely associated with goddesses and divine or dead queens. Experts are divided over the subject of this head: it has been variously identified as Cleopatra VII, Berenice II and the goddess Isis.

We were still two or three hours’ steaming distance before land could possibly be in sight, when suddenly we saw, inverted in the sky, a perfect miragic reproduction of Alexandria, in which Pharos Light, Ras-el-Tin Palace, and other prominent features were easily distinguishable. The illusion continued for a considerable time, and eventually as suddenly disappeared, when, an hour or two later, the real city slowly appeared above the horizon! A good augury, surely, of the wonders I hoped to discover on landing!

.

R. T. Kelly,

Egypt

1

T

he pharaohs of old had founded many capital cities. The northern city of Memphis, situated at the junction of the Nile Valley and the Nile Delta, just a few miles to the south of modern Cairo, was the first and most ancient. Here the thoughtful creator god Ptah dwelt in his extensive stone temple, and here the kings of the Old Kingdom raised their pyramids in the desert cemeteries of Sakkara and Giza. Cosmopolitan Memphis would remain the administrative centre of

Egypt for much of the dynastic age. Four hundred miles to the south lay proud Thebes, home of the warrior god Amen-Re and, during the New Kingdom, home and burial place of the elite whose rock-cut tombs honeycombed the east-bank Valleys of the Kings and Queens. Shorter-lived were Itj-Tawi (built by the Middle Kingdom pharaohs and now entirely lost), Akhetaten (Amarna: Akhenaten’s Middle Egyptian city of the sun god) and the Delta cities of Per-Ramesses (Tell ed Daba), Tanis (San el-Hagar) and Sais (Sa el-Hagar). All these cities were built at a time when inward-looking Egypt was able to flourish in splendid isolation, and none allowed easy access to the outside world.

Silver tetradrachm of Alexander the Great who appears as Heracles dressed in a lion skin

.

In 332, when Alexander the Great arrived in Egypt, Memphis was again serving as the capital city. Realising Egypt’s need for a modern, outward-looking city-seaport, Alexander sailed along the Mediterranean coast, inspected various sites, consulted his architects and was on the verge of making a decision. Then, as Plutarch tells us, he had a vivid dream:

… in the night, as he lay asleep, he saw a wonderful vision. A man with very hoary locks and of a venerable aspect appeared to stand by his side and recite these verses: ‘Now, there is an island in the much-dashing sea, in front of Egypt; Pharos is what men call it.’ Accordingly, he rose up at once and went to Pharos, which at that time was still an island, a little above the Canopic mouth of the Nile, but now it has been joined to the mainland by a causeway. And when he saw a site of surpassing natural advantages (for it is a strip of land like enough to a broad isthmus, extending between a great lagoon and a stretch of sea which terminates in a large harbour), he said he saw now that Homer was not only admirable in other ways, but also a very wise architect, and ordered the plan of the city to be drawn in conformity with this site.

2

The wise old man of the night was Alexander’s great hero Homer, and the lines that he quoted were from Book 4 of his

Odyssey

, a part of the tale where Menelaos finds himself stranded in Egypt. Such exalted advice could not be ignored, and Alexander hastily revised his plans. Pharos island was clearly too small to house a great city. But on the mainland, opposite Pharos, was Rakhotis, an old and undistinguished fishing village which in better days had served as a pharaonic customs post and a Persian fortress.

3

Alexander made up his mind. His new city, Alexandria, was to be built around Rakhotis (Ra-Kedet), on a limestone spur running between the Mediterranean to the north and the freshwater Lake Moeris (Lake Canopus) to the south. The sea would allow easy contact with the Hellenistic world; canals running into the lake would allow contact with the River Nile, southern Egypt and Africa beyond Egypt. The omens were propitious: as the architects marked out the city boundaries in barley flour, flocks of birds swooped down to feed. Clearly, Alexandria would soon be fertile enough to feed the world.

The Greek historian Arrian tells a less romantic, more practical, but essentially similar story. Alexander again chooses the city site himself and is involved in its planning: