Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (30 page)

Read Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Egypt, #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State

As many historians have observed, suicide by snakebite is not the easy matter that it might first appear, particularly when one snake is expected to kill three people. At best it would be a risky business with

a high chance of failure. One cannot, after all, force a reluctant snake to bite and, even if the snake does bite, not every bite injects poison and not every poisoned bite kills. And, as most of the poison is injected with the first bite, it is unlikely that one snake would kill three adults with three consecutive strikes. In Cleopatra’s case, the preliminaries would have been fraught with the additional danger of detection. If we accept Octavian’s often expressed desire to keep Cleopatra alive, we must assume that she was effectively on ‘suicide watch’: an order for a snake would have had to be smuggled out of the palace, and the snake would have had to be smuggled back in. Although relatively slender, the Egyptian cobra,

Naja haje

, the principal suspect, can grow to just over six feet in length. An adult cobra, or three, would have needed an exceptionally large fig basket or water jar.

However, in the absence of any obvious weapon, death by snakebite was accepted by everyone as a symbolically suitable means of female royal suicide. Egypt is currently home to some thirty-nine varieties of snake and there seems no reason to assume that things were very different in antiquity.

20

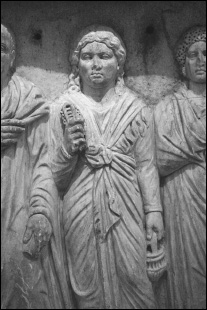

The dynastic Egyptians had a love-hate relationship with these snakes. They knew all too well that snakes could kill, but they also knew that snakes played an important role in pest control. A snake living beside the granary was infinitely preferable to a nest of rats. This ambivalent attitude is best expressed in the pantheon, home to both good and bad snakes. The serpent Apophis was pure evil: every night he attacked the boat of the sun god Re as it sailed through the dark and dangerous underworld. Fortunately Re had the tightly coiled good snake god Mehen to protect him. Female snake deities were considered to be exemplary mothers. We have already met Wadjyt, ‘The Green One’, the cobra goddess of the Nile Delta, who appears as the uraeus that decorates and protects the royal crown. Meretseger, ‘She Who Loves Silence’, guarded the dead of the Theban cemetery. Renenutet, a deadly hooded cobra, was the goddess of the harvest. She protected granaries and families and, as a divine

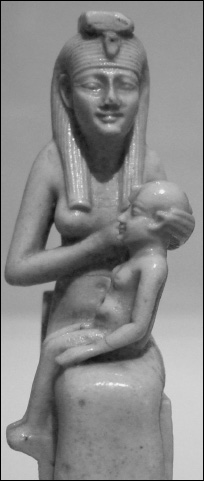

nurse, cared for both babies and the king. Isis, herself a famously good mother, occasionally appeared as the snake Isis Thermoutharion. Alexandria even had its own protective snake deity.

The Alexander Romance

tells how the workmen who built the city were pestered by a snake. Alexander had the snake killed, then built a sanctuary on the spot where it had died. Soon the sanctuary filled with snakes, which squirmed into the neighbouring houses. These were known as the Agathoi Daemones, ‘The Good Spirits’.

The Macedonian royal family, too, took a keen interest in snakes. We have already read the story of Nectanebo II assuming the form of a snake to father Alexander the Great (page 132). A variant on this tale is told by Plutarch:

A serpent was once seen lying stretched out by the side of Olympias as she slept, and we are told that this, more than anything else, dulled the ardour of Philip’s attentions to his wife, so that he no longer came often to sleep by her side, either because he feared that some spells and enchantments might be practised upon him by her, or because he shrank from her embraces in the conviction that she was the partner of a superior being. But concerning these matters there is another story to this effect: all the women of these parts were addicted to the Orphic rites and the orgies of Dionysos from very ancient times, and imitated in many ways the practices of the Edonian women and the Thracian women about Mount Haemus, from whom, as it would seem, the word ‘threskeuein’ came to be applied to the celebration of extravagant and superstitious ceremonies. Now Olympias, who affected these divine possessions more zealously than other women, and carried them out in wilder fashion, used to provide the revelling companies with great tame serpents, which would often lift their heads from out the ivy and the mystic winnowing-baskets, or coil themselves about the wands and garlands of the women, thus terrifying the men.

21

17. The ‘Alabaster Tomb’ of Alexandria: resting place of Alexander the Great?

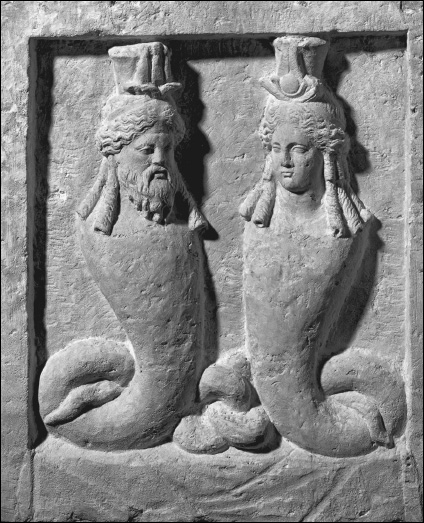

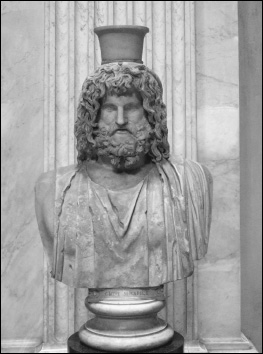

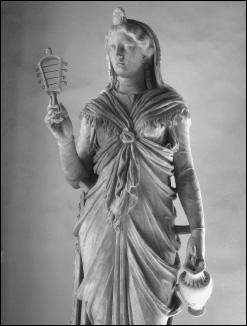

18. The god Serapis, consort of Isis and patron deity of Alexandria.

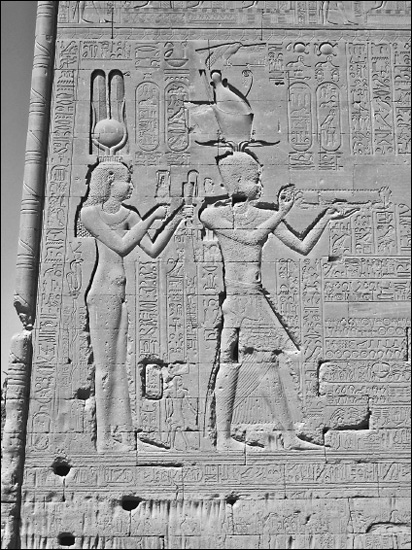

23. Isis carries the sistrum, or sacred rattle, which has the power to stimulate the gods.