Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness (109 page)

Read Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness Online

Authors: Fabrizio Didonna,Jon Kabat-Zinn

Tags: #Science, #Physics, #Crystallography, #Chemistry, #Inorganic

just kind of didn’t matter. It didn’t matter where I got it from.

Sylvia described increased

acceptance

of what is occurring in the present

moment.

So, I learned how to be in the present and I use that a lot on a daily basis –

when I’m stressed out, you know even in traffic. You say, “I’m here now. This

is where I’m going to be. I’ll worry about the grocery store later.” I just accept

things a lot easier now than I did before.

Issues around

spirituality

, encompassing feelings of hope, peace, and

understanding, surfaced and resonated strongly with Sylvia despite that the

focus of the MBSR program is secular and does not specifically address

spirituality.

After the [full-day meditation] retreat I said that I was at such peace and it was

so spiritual

. . .

The increased feelings of spirituality and peace expressed by Sylvia had

particular implications related to her own experience of cancer.

I’m at peace. I understand it [the cancer] a lot better. I understand it. And if it

recurs, I think I’m prepared for that. [

. . .

] I know things happened for a reason,

always. Always.”

This comment is congruent with the definition of spirituality as an ability

to see the divinity, or greater organization in life, and to use this understand-

ing to deal with life challenges.

Significant increases in

PTG

were also evident in Sylvia’s interview. She

described experiencing positive changes related to the cancer experience

after participation in the program, and linked specific skill acquisition in deal-

ing with the cancer experience to her participation in the MBSR course.

I always knew that there was something that I had to learn from this and I

never knew what it was – I never knew. And I think now what I’ve learned

(and probably from the course) is, what I’ve learned is to appreciate things, to

take time for things, which I think before I was always so busy and always so

controlling, and you know, quite bossy. I realized that you can’t do anything

about the cancer but you can do something about how you feel about it and

how you react to it.

It is clear from this interview that many of the themes of the program

resonated with Sylvia’s experience of learning MBSR, particularly around

Chapter 20 Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Oncology

395

issues of feeling a need to know and have some certainty about why can-

cer occurred, and whether it was coming back. This inherent uncertainty

in the illness experience is often one of the most difficult issues for cancer

survivors to live with. Sylvia’s comments provide some insight into how the

program can help patients find peace even within this vast inability to know

the future with any degree of certainty. Somehow through the practice she

learned to tolerate uncertainty and uncontrollability much better than before

her cancer experience.

Sylvia’s responses during this qualitative interview represent only one

patient’s perception of the effects of MBSR on positive and negative out-

comes, but do resonate well with what other patients have articulated. The

interviews in general reveal a broad range of improvements related to a

greater appreciation for life and improved coping self-efficacy. Encourage-

ment of the adoption of attitudes such as acceptance and letting go appear

to have contributed to patients’ increased feelings of spirituality and PTG,

and decreased stress and mood disturbance. Based on qualitative analyses,

there appears to be a strong link between mindfulness practice and a health-

ier view of the cancer experience and its impact on daily functioning.

Summary and Conclusions

Distress and other negative reactions to a cancer diagnosis and all that it

entails are common and expected experiences for cancer patients and their

families. Fears of premature death and of the pain and indignities of can-

cer treatment are natural and well founded in many cases. Despite the hur-

dles such experiences present, patients are often able not only to adjust to

such a massive life stress, but even to thrive and grow as a result. We have

reviewed the rational suggesting MBSR may be helpful for cancer patients

and families, and provided an overview of the clinical research detailing its

efficacy for alleviating a wide range of negative outcomes including stress

symptoms, anxiety, anger, fear, sleep disturbance and depression. We have

also shown evidence of enhancement in overall quality of life, improved

ability to find benefit in the situation and grow through trauma, includ-

ing enhancement of a sense of spirituality and meaning and purpose in

life, as well as enhanced ability to tolerate uncertainty. In addition to these

psychological benefits, patients often show improved biological regulation

of a variety of circadian systems that are essential to promote health and

homeostasis, such as cytokine expression, cortisol secretion, and blood pres-

sure. We have attempted to integrate methods of inquiry including both

qualitative and quantitative approaches in the hopes of better understand-

ing not only the outcomes of MBSR in people living with cancer, but also

the potential mechanisms that may help to explain how and why MBSR

is effective in this group. Future research efforts of our group and others

should help to lend further understanding not only to the full range of

effects of MBSR, but also some insight into these intriguing questions of

how and why.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Linda E. Carlson holds the Enbridge Endowed

Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology, co-funded by Enbridge Inc., the

396

L.E. Carlson et al.

Canadian Cancer Society, and the Alberta Cancer Foundation. Laura E. Labella

is funded by an Alberta Heritage Foundation Medical Research PhD Schol-

arship and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Counsel of Canada

PhD Fellowship, and Sheila Garland is funded by the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Counsel of Canada PhD Fellowship. The research

described in this chapter has been funded by the Canadian Institutes of

Health Research, National Cancer Institute of Canada, Canadian Breast Can-

cer Research Alliance, and Calgary Health Region through grants awarded to

Dr. Linda E. Carlson. None of this work would be possible without the co-

operation and dedication of the patients who have given generously of their

time to participate in our research programs – heartfelt thanks are extended

to them all.

Appendix: Description of Specific Didactic Learning and

Experiential Exercises

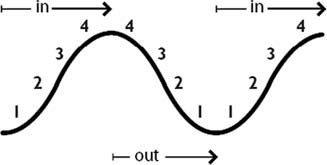

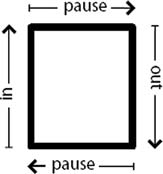

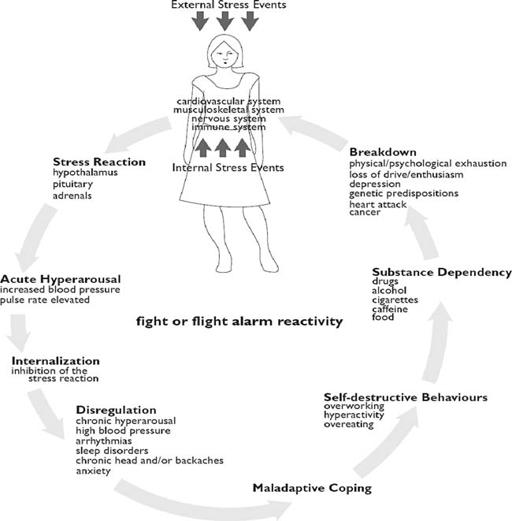

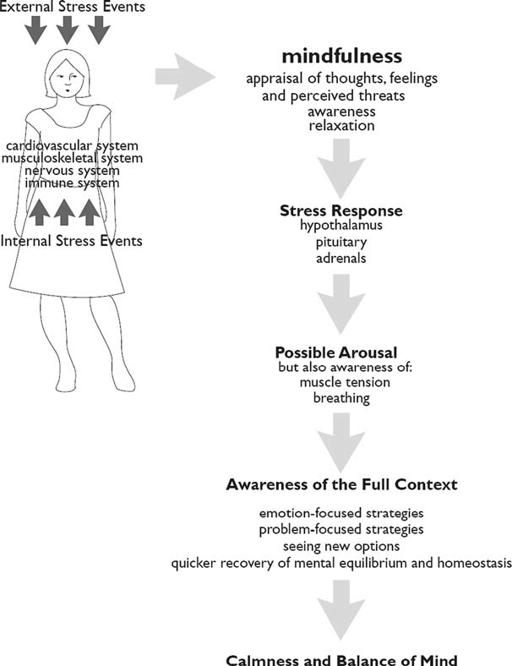

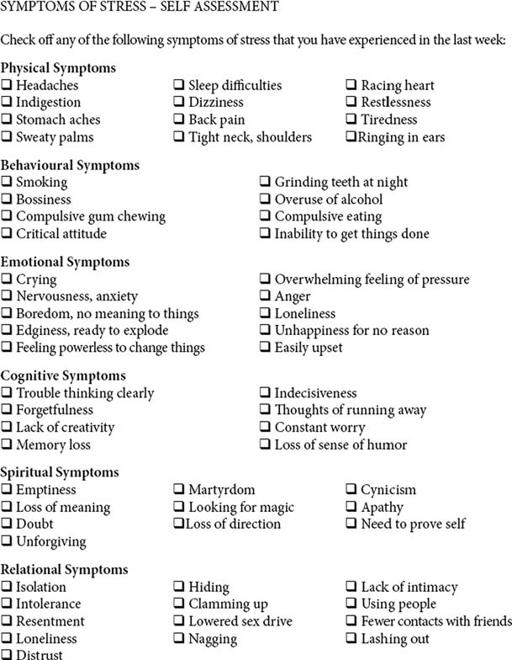

Following group discussion and problem solving about home practice, the

didactic components of Week 3 (“Mind-body Wisdom and Healing”) and

Figure. 20.1.

The stress reaction.

Chapter 20 Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Oncology

397

Week 4 (“Balance in the Autonomic Nervous System”) in our MBSR pro-

gram include a description of the automatic physical, emotional and behav-

ioral reaction to stress, compared with the response when we choose

to attend mindfully to our experience. Short and long-term emotional,

cognitive, behavioral, and physiological aspects of these two different

responses are illustrated and discussed (Figures

20.1

and

20.2;

adapted from

Kabat-Zinn, 1990).

In addition, participants complete a self-assessment checklist of symptoms of stress, in order to develop awareness of the

ways in which stress may influence emotions, sensations, and behaviors

(Figure

20.3).

In Weeks 3 and 4, following didactic instruction, participants are guided

through a series of experiential exercises involving bringing awareness to

Figure. 20.2.

The stress response.

398

L.E. Carlson et al.

Figure. 20.3.

Symptoms of stress self-assessment.

the breath. These are taught in conjunction with the basic sitting medita-

tion and yoga postures that occur during each weekly class. These exercises

are referred to as “mini” mindfulness exercises. “Minis” are focused breathing

techniques that are practiced to help reduce anxiety and tension in any place,

at any time, and can be engaged in without others taking notice. For example,

“minis” can be performed when stuck in traffic, when feeling overwhelmed,

when waiting in the doctor’s office, waiting in line or when experiencing

pain. Participants are guided through the experience of mindful slow, deep

diaphragmatic breathing then use the various techniques to focus breath pat-

terns and awareness (Figures

20.4–20.8).