Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness (58 page)

Read Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness Online

Authors: Fabrizio Didonna,Jon Kabat-Zinn

Tags: #Science, #Physics, #Crystallography, #Chemistry, #Inorganic

follow-up.

More than a therapeutic technique, it might be more appropriate to say

that PEV is a mindful mental style or attitude. It is an alternative way for OCD

patients to relate to themselves and their experience, helping them see that

certainty is unnecessary because the information that they already possess is

sufficient.

OCD Problem Formulation and Mindfulness

As has been pointed out by

Teasdale et al. (2003),

when a mindfulness-based intervention is provided for individuals with specific disorders, it is particularly important to share with patients, both in individual and group settings,

a clear problem formulation explaining the potential role of the mindful state

in order to prevent the maintaining mechanisms of the disorder. Mindfulness

training is effective when it is linked to coherent alternative views of patients’

problems, views that are shared with patients and reinforced through the

mindfulness practices

(Teasdale et al., 2003).

Chapter 11 Mindfulness and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

207

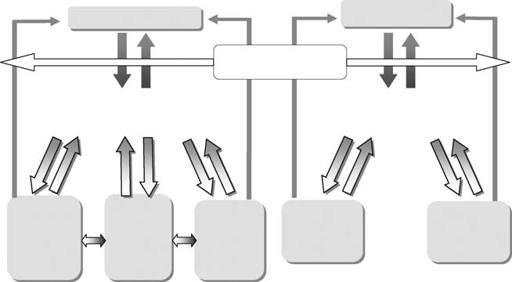

Anxiety disorders are activated and maintained by dysfunctional metacog-

nitions about normal and innocuous mental events. Following the standard

cognitive conceptualizations of psychological disorders, the clinical rele-

vance of mindfulness for several diseases, and for OCD too, might lie in its

intervening at a radical and hierarchically superordinate level, in particular,

at a point between inner and outer activating stimuli and the metacognitive

processes and maintaining mechanisms conducive to psychological distress

(Figure 11.3). Mindfulness, which is a

being mode

(see Chapter 1), can be

cultivated to prevent or deactivate the metacognitive processes which lead

patients into the vicious, self-perpetuating cycles of obsessions and the asso-

ciated counterproductive behaviors.

(Didonna, 2006, 2008).

If we compare OCD with a related diagnosis such as panic disorder, we

can observe that in both disorders the problem stems from how some nor-

mal experiences are perceived (Figure 11.3). Looking at a standard cognitive

model of these problems, in the case of the obsessive-compulsive syndrome,

the trigger is normally an intrusive cognition, while in panic disorder, in the

trigger is one or more normal physical sensations. Subsequently, the patient

starts to interpret these normal experiences as dangerous (metacognition),

which in the case of OCD may involve a pervasive idea of responsibility

for harm or damage, while in panic disorder it will involve a thought of

imminent catastrophe. These two meta-evaluations then activate the main-

tenance mechanisms of the two disorders: “Doing mode” (neutralization,

rituals, seeking reassurance, rumination) and cognitive biases (perceptive

self-invalidation, attentional biases, thought-action fusion, non-acceptance

bias) on the one hand and

safety seeking behavior

on the other (avoid-

ance, flight, etc.), but also emotional states, anxiety, guilt, shame, disgust,

depression in OCD and anxiety in Panic, which will reinforce the initial

metacognitions that maintain the disorder. Compulsions, neutralizations,

and safety behaviors are acts that are performed in an attempt to reduce

Obsessive-Compulsive

Panic

Disorder

normal sensations

normal intrusive cognitions

State of Mindfulness

FACTORS

(“bein

ng mode””)

META-EVALUATION

Misinterpretation of intrusions

META-EVALUATION

based on hyperactivation of OCD belief

misinterpretation of sensations

ACTIVATING

domains (e.g. inflated responsibility)

In terms of catastrophic belief

Perceptive self-

“Doing mode”

“Doing mode”

invalidation,

Emotional

neutralization,

Safety-seeking

attentional

states

Anxiety

rituals,

Behaviour

biases,

reassurance,

(anxiety, guilt,

(avoidance and

thought-action

rumination

fusion, non-

shame, disgust

flight)

acceptance

depression)

MAINTENANCE FACTORS

Figure. 11.3.

A cognitive formulation of the role and effects of mindfulness state and

practice with respect to the activating and maintenance factors in OCD and panic

disorder.

208

Fabrizio Didonna

the perceived threat and the anxiety and distress caused by the metacog-

nitions, but the relief is only temporary: indeed, these behaviors increase,

rather than reduce, the anxiety. These reactions maintain the problem and

prevent habituation to the anxiety and disconfirmation of the patient’s fears

(Didonna,

Salkovskis, 1996,

2006, 2008).

The activation of a mindful state (a “being mode”) intervenes at an early

stage in the activation of the symptoms of these disorders, allowing the

patient to take a different attitude toward “normal” internal initial experi-

ences (thoughts, sensations) from the moment he/she becomes aware of

them, by means of an accepting, self-validating, and non-judgmental attitude.

Such an attitude, cultivated through mindfulness practice, prevents the acti-

vation of those meta-evaluational processes that would otherwise give rise to

the anxious syndrome (Figure 11.3).

Mindfulness training can help OCD patients inhibit secondary elaborative

processing of the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that arise in the stream

of consciousness and may cause improvements in cognitive inhibition,

particularly at the level of stimulus selection

(Bishop et al., 2004).

This effect can be objectively evaluated using specific tests that involve the inhibition

of semantic processing (e.g., emotional Stroop; Williams, Mathews, &

MacLeod,

1996).

Integrating CBT and Mindfulness

Always do what you are afraid to do!

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Unlike standard CBT, in mindfulness-based interventions the main goal is

not to change the content of the patient’s system of cognitions but rather to

change his or her way of relating to it. During mindfulness training, patients

are helped to shift from a focus on the past and on the future (conditioned

by memories and rumination) to a focus on the present moment, develop-

ing a process of

decentering

and

disidentification

from personal experi-

ence

(Segal et al., 2002).

Mindfulness-based treatments focus on altering the

impact

of and

response

to thoughts, emotions and sensations. It can thus be

particularly effective for a disorder like OCD in which intolerance of negative

inner experience and consequent behavioral avoidance play a central role.

Nevertheless, carrying out mindfulness interventions with obsessive

patients is not always easy, especially in the case of patients with severe or

chronic suffering. Such patients normally have rigid schemata and attitudes

toward their inner experience. One solution to this challenge also suggested

by other authors

(Schwartz & Beyette, 1997;

Hannan & Tolin, 2005;

Wilhelm

& Steketee,

2007;

Fairfax, 2008),

and that is adopted at the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Unit in Vicenza, is to integrate CBT with a mindfulness-based

intervention. This integration may be usefully provided in three phases, sum-

marized as follows:

(1)

Problem formulation

. This may be done during some preliminary ses-

sions in which therapist and patient reach a clear and shared conceptu-

alization of the activating and maintaining factors of OCD

(Salkovskis,

1985)

and the possible role and effects of mindfulness in this pro-

cess (see Figure 11.3). This allows the patient to understand how

Chapter 11 Mindfulness and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

209

his/her problem works and how mindfulness training might challenge

the dysfunctional mechanisms highlighted by the problem formulation.

Mindfulness may ameliorate OCD deficits, change the modes and the

maintaining factors of the disorder, help the patient modify how he/she

relates to the entire experience (inner and outer), and develop a new

way of being

.

(2)

Training

patients in Mindfulness skills. For this purpose it is useful to

provide patients with an already established and structured mindfulness-

based group, such as MBCT or MBSR, that has been adapted for OCD

patients. In this group, the importance and effects of exposure are high-

lighted, psychoeducational materials provided, and an explanation given

of how obsessive individuals relate to their thoughts, emotions and per-

ceptions. The mechanisms by which mindfulness can alter dysfunctional

OCD attitudes are also illustrated.

(3)

Integrating Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) techniques and

mindfulness

using

mindful exposure

. Unlike classical ERP techniques,

in this form of exposure, the patient is continuously invited to stay

directly in touch with his/her private experience, carefully noticing,

moment by moment, the real cognitive, sensory and emotional expe-

rience which arises during exposure, without judgement, evaluation or

reaction to it, preventing on purpose any metacognitive processes on

the real experience, or seeing any metacognitions as simply thoughts,

and passing through it.

Anecdotal clinical experience with dozens of patients with OCD has sug-

gested that sessions (in individual or group setting) should follow the follow-

ing format (see Figure 11.4):

Practice of mindfulness

(Mindfulness of breath/body)

Exposure (in vivo or imagery) to anxiogenic stimuli

“Breath as an anchor”

Awareness of thoughts, sensations, feelings and emotions

and actively observing and describing private experience without judgment

Using allowing, ‘letting be’, acceptance attitudes towards

thoughts, sensations and emotional states

Using decentering, defusion and disidentification strategies;

‘thoughts as impermanent mental facts’

Using metaphors (e.g. “thoughts like clouds in the sky”)

Response Prevention – avoiding any overt and covert reaction to private

experience

(neutralizations, rituals, reassurance seeking)

Short mindfulness exercise (e.g. Breathing space)

Figure. 11.4.

Example of an integrated model of exposure and response prevention

procedure and mindfulness-based intervention.

210

Fabrizio Didonna

(A) The session should start by inviting the patient to practice a mindfulness

exercise which allows him/her to enter into a stable, balanced and wake-

ful state of mind (e.g., sitting meditation, body scan – see Appendix A),

fully opening attentive and sensory processes.

(B) The patient should be exposed (in vivo or imaginal exposure) to anxiety-

provoking or distressing situations or triggers. In each moment of this

phase, it is important to invite the patient to bring attention to an

“attentional anchor” or “mindfulness center” (e.g., the body or a sensory

input such as breathing) in order to be centered in the present moment

(“breathing as an anchor”) observing whatever happens in the inner and

outer experience.

(C) The patient should pay attention and bring awareness to any thoughts,

sensations, feelings and emotions that may arise and actively observe and

describe this private experience over and over again without judgment.

For example, anxiety may be described by the patient as an array of

innocuous physical sensations and thoughts whose increase cannot lead

to any dangerous consequences.

(D) The attitudes to be used are allowing, “letting be,” and acceptance

attitudes (learned at the mindfulness training) toward thoughts, sen-

sations and emotional states. Decentering, defusion and disidentifica-

tion strategies are used and for this purpose it might be useful to use