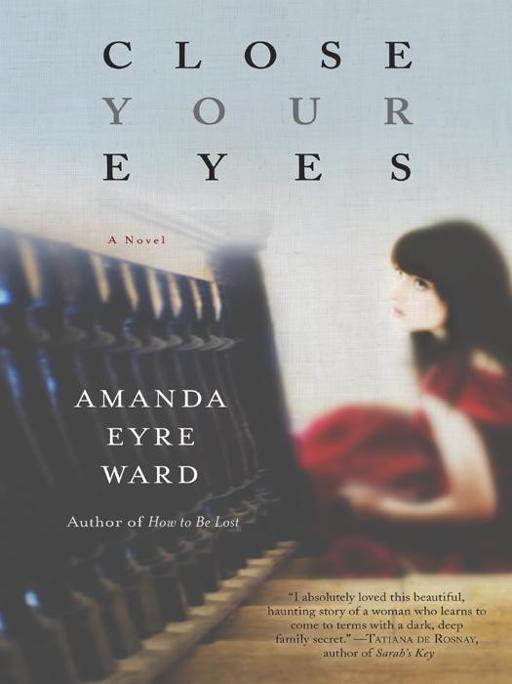

Close Your Eyes

Authors: Amanda Eyre Ward

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Sagas, #Literary, #General

ALSO BY AMANDA EYRE WARD

Love Stories in This Town

Forgive Me

How to Be Lost

Sleep Toward Heaven

Close Your Eyes

is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Amanda Eyre Ward

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Ward, Amanda Eyre

Close your eyes: a novel/Amanda Eyre Ward.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60508-9

1. Family secrets—Fiction. 2. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3623.A725C57 2010

813′.6—dc22 2010021115

v3.1

A sister is … a golden thread to the meaning of life.

—ISADORA JAMES

This book is for my sister, Sarah, with love

.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Prologue

A

UGUST

1986

I can remember the taste of ocean, and the dark smell of impending rain. Our parents had given us reluctant permission to spend the night in the tree house. From our perch, high in an oak tree, we could see a faraway sliver of Long Island Sound. I can almost see myself—the way I looked before: a sweet girl, just eight. I was sturdy, like my father, with his dark hair and olive skin. My mother brushed my hair into pigtails, and I wore sundresses with bare feet, so I could climb.

My brother, Alex, had stolen a can of Tab from the pantry. We drank from plastic teacups, remnants of my girlhood set. Clouds moved over the moon. My L.L.Bean sleeping bag was too warm, and in the middle of the night, I slipped one leg outside the heavy fabric and touched my brother’s foot with my own.

The tree house was a small structure shaped like a pirate ship. My mother used to laugh and say it had taken longer for my father to build the damn thing than it had for her to grow and deliver a baby, but by the time I was two and could climb the ladder to the top, it was finished.

We had a large, grassy yard; from the tree house, you could barely see the peeling paint on our back door. No matter what happened inside, as it turned out, you wouldn’t hear a sound.

That night, our parents had given a small party. Alex and I often hid during their gatherings, and watched the adults drink wine and act strange. My father grilled elaborate Egyptian dishes on the Weber—rice-stuffed pigeon, rabbit with mint—and my mother sat with her friends at the picnic table and smoked cigarettes furtively, the embers lending her face an angelic glow. The guests that night were Phil Salinas, an investment banker; Jessica Salinas, his newest wife; Adam Schwickrath, an orthopedic surgeon; and Donna Halsey, my piano teacher.

My father teased my mother about Adam Schwickrath. He was the man she should have married, my father said, his words edged with bitterness. Dr. Schwickrath was wealthy and well dressed, usually wearing khakis and a button-down shirt. Some evenings he and my mother would talk to each other in soft tones, my mother laughing and lifting her head to expose her throat.

Dr. Schwickrath had given my mother a wrapped package that night, though her birthday had been weeks before. “Better late than never,” he’d said, almost bashfully. As my mother opened the box and took out a pair of high-heeled shoes, I’d looked at my father, who was staring, his jaw set. He had written my mother a birthday poem, made her a pan of walnut brownies. “I just thought of you when I saw them, Jordan,” said Mr. Schwickrath.

“Are they the right size?” asked my father.

My mother had peered at the strappy shoes. They were a silvery color, more expensive than anything we could afford, I knew. “Adam, how did you know I was a size seven? They’re beautiful!” my mother had said. She held a shoe to the light, admiring. But her hand fell when she saw my father’s face. “Oh, never mind!” she said brightly, dropping the shoes back in their box and placing it on a chair. “Let’s have some appetizers, why don’t we?”

Alex and I snacked on corn chips, answering stupid questions about soccer, long division, and what we wanted to be when we grew up. Alex, who was ten, wanted to be a fighter pilot and I, a ballerina. At long last, our parents said we could take our leave.

We climbed the ladder quietly and lit the candle we’d taken from the sideboard. The caramel light made the tree house seem otherworldly. It may have taken him a while, but my father had built our hideout with care, lining up each board, framing windows.

My father loved to tinker in his basement workshop. My mother earned the money to pay for our real house, but my father took bits of driftwood or discarded lumber and assembled other dwellings. Besides the tree house, he made me a dollhouse that I called the Fairy Lair. He told me long stories about the fairies who lived inside, and sometimes I would come home from school to find a new piece of furniture: a bed made of daisies or a bathtub carved from wood, painted with flowers. He made birdhouses and gave them to friends as gifts.

My father. He smelled like cigarettes and cardamom. When I was small and wanted comfort, he would put down the wooden spoon when he was cooking, or the pen when he was writing. Always, he would halt what he was doing and crouch down. I would press my cheek to his warm chest. In his arms, I was safe.

The sleeping bags nearly filled the tree house. Alex poured the soda, and I heard my mother’s laughter as I sipped. Sometimes, when I concentrate, I can still hear her.