Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition

Read Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition Online

Authors: H. P. Lovecraft

Collected Fiction

A VARIORUM EDITION

VOLUME 2: 1926–1930

Edited by S. T. Joshi

Hippocampus Press

—————————

New York

Copyright © 2016 by Hippocampus Press.

Selection, editing, and editorial matter copyright © 2015 by S. T. Joshi.

Lovecraft material used by permission of the Estate of H. P. Lovecraft; Lovecraft Properties, LLC.

First Electronic Edition.

Published by Hippocampus Press

P.O. Box 641, New York, NY 10156.

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

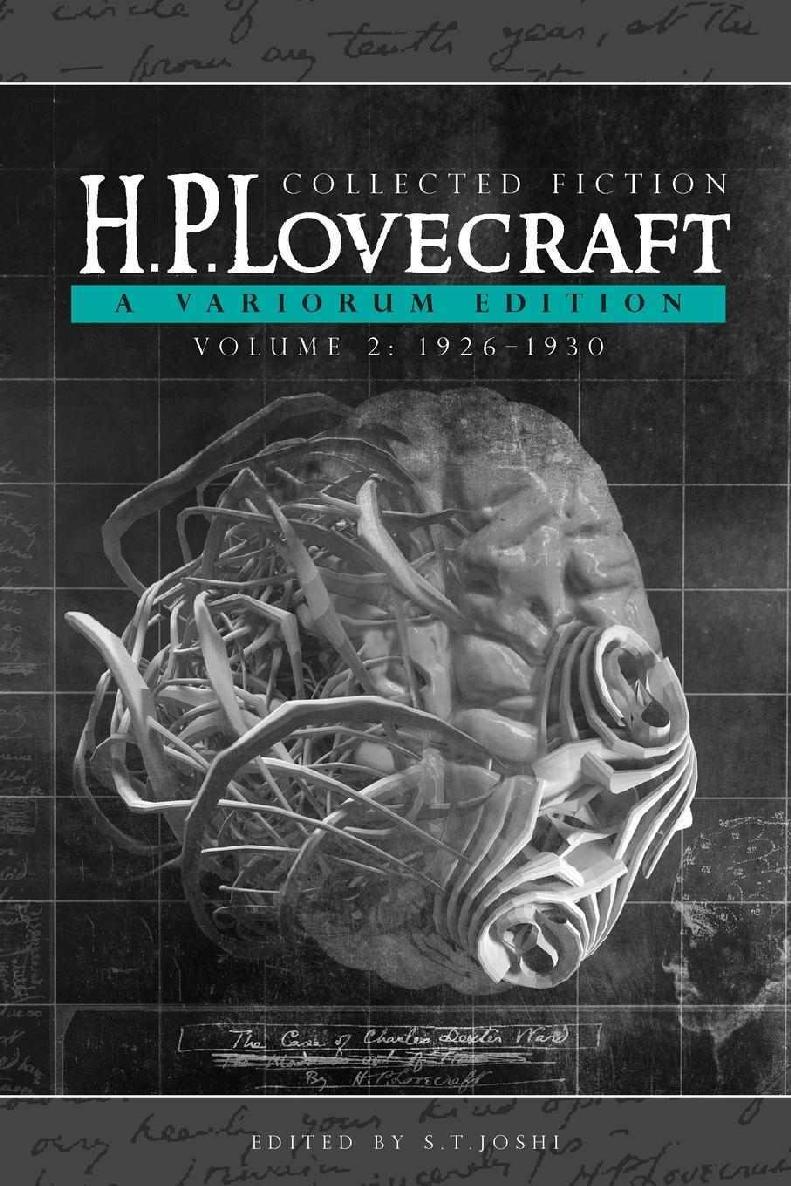

Cover design and cover artwork by Fergal Fitzpatrick. For the cover of volume two, Mr. Fitzpatrick has used

abstract truth and scientific logic

as his conceptual departure.

abstract truth and scientific logic

as his conceptual departure.

“I should describe mine own nature as tripartite, my interests consisting of three parallel and dissociated groups—(a) Love of the strange and the fantastic. (b) Love of the abstract truth and of scientific logick. (c) Love of the ancient and the permanent. Sundry combinations of these three strains will probably account for all my odd tastes and eccentricities.”

—H. P. Lovecraft to Rheinhart Kleiner (7 March 1920)

Portrait of H. P. Lovecraft, c 1930.

Photo of S. T. Joshi by Emily Marija Kurmis.

Hippocampus Press logo designed by Anastasia Damianakos.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ISBN: 978-1-61498-169-5 Kindle

ISBN: 978-1-61498-170-1 Epub

ContentsIntroduction

The stories in this volume constitute, on the whole, a body of work that first appeared in pulp magazines without initial publication in amateur journals. As a result, Lovecraft did not have much of an opportunity to revise these texts, as he had done for many of the stories that had first appeared in amateur periodicals. Two exceptions to this rule are “Pickman’s Model” (which was slightly revised for its second appearance in

Weird Tales

) and “The Colour out of Space” (which was revised for a proposed book publication by F. Lee Baldwin that never eventuated).

Weird Tales

) and “The Colour out of Space” (which was revised for a proposed book publication by F. Lee Baldwin that never eventuated).

Lovecraft’s two short novels,

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath

and

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward,

lay unpublished at the time of his death. He made no effort to prepare these texts for publication, although R. H. Barlow prepared partial typescripts of them (both of which contain slight revisions and corrections by Lovecraft). It would, however, be inaccurate to say that these stories are mere first drafts; the extent to which Lovecraft revised them in the course of composition bespeaks considerable care in matters of structure and style.

Dream-Quest

is slightly less revised than

Ward,

true to its nature as a “practice” novel (

SL

2.95).

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath

and

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward,

lay unpublished at the time of his death. He made no effort to prepare these texts for publication, although R. H. Barlow prepared partial typescripts of them (both of which contain slight revisions and corrections by Lovecraft). It would, however, be inaccurate to say that these stories are mere first drafts; the extent to which Lovecraft revised them in the course of composition bespeaks considerable care in matters of structure and style.

Dream-Quest

is slightly less revised than

Ward,

true to its nature as a “practice” novel (

SL

2.95).

The two humorous squibs, “History of the ‘Necronomicon’” and “Ibid,” also remained unpublished until after Lovecraft’s death, as did the fragment “The Descendant.” “Ibid” is the only work in this volume for which a manuscript has not come to light. It was presumably sent to Maurice W. Moe, and its whereabouts among Moe’s effects are unknown. For “The Colour out of Space,” we do not have Lovecraft’s original A.Ms. or T.Ms., but a T.Ms. presumably prepared by Baldwin, revised by the author.

Of the texts in this volume, “The Call of Cthulhu” and the two short novels were very poorly printed by Arkham House, because it unwisely chose (in the case of “The Call of Cthulhu”) to follow the poor

Weird Tales

text, and (in the case of the novels) because whoever transcribed the texts exhibited a poor ability to read Lovecraft’s handwriting. Such major stories as “The Colour out of Space,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness” were well printed by Arkham House because it followed Lovecraft’s T.Ms.

Weird Tales

text, and (in the case of the novels) because whoever transcribed the texts exhibited a poor ability to read Lovecraft’s handwriting. Such major stories as “The Colour out of Space,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness” were well printed by Arkham House because it followed Lovecraft’s T.Ms.

The dream-account later titled “The Very Old Folk” was written in late 1927, embodied in a letter to Donald Wandrei. It appears in the Appendix to Volume 3.

Abbreviations used in the notes are as follows:

A.Ms. autograph manuscript

JHL John Hay Library, Brown University (Providence, RI)

om.

omitted

omitted

SL Selected Letters

(1965–76; 5 vols.)

(1965–76; 5 vols.)

T.Ms. typed manuscript

—S. T. JOSHI

Collected Fiction: 1926–1930Cool Air

You ask me to explain why I am afraid of a draught

[1]

of cool air; why I shiver more than others upon entering a cold room, and seem nauseated and repelled when the chill of evening creeps through the heat of a mild autumn day. There are those who say I respond to cold as others do to a bad odour,

[2]

and I am the last to deny the impression. What I will do is to relate the most horrible circumstance

[3]

I ever encountered, and leave it to you to judge whether or not this forms a suitable explanation of my peculiarity.

[1]

of cool air; why I shiver more than others upon entering a cold room, and seem nauseated and repelled when the chill of evening creeps through the heat of a mild autumn day. There are those who say I respond to cold as others do to a bad odour,

[2]

and I am the last to deny the impression. What I will do is to relate the most horrible circumstance

[3]

I ever encountered, and leave it to you to judge whether or not this forms a suitable explanation of my peculiarity.

It is a mistake to fancy that horror is associated inextricably with darkness, silence, and solitude. I found it in the glare of mid-afternoon,

[4]

in the clangour of a

[5]

metropolis, and in the teeming midst of a shabby and commonplace rooming-house with a prosaic landlady and two stalwart men by my side. In the spring of 1923 I had secured some dreary and unprofitable magazine work in the city of New York; and being unable to pay any substantial rent, began drifting from one cheap boarding establishment to another in search of a room which might combine the qualities of decent cleanliness, endurable furnishings, and very reasonable price. It soon developed that I had only a choice between different evils, but after a time I came upon a house in West Fourteenth Street which disgusted me much less than the others I had sampled.

[4]

in the clangour of a

[5]

metropolis, and in the teeming midst of a shabby and commonplace rooming-house with a prosaic landlady and two stalwart men by my side. In the spring of 1923 I had secured some dreary and unprofitable magazine work in the city of New York; and being unable to pay any substantial rent, began drifting from one cheap boarding establishment to another in search of a room which might combine the qualities of decent cleanliness, endurable furnishings, and very reasonable price. It soon developed that I had only a choice between different evils, but after a time I came upon a house in West Fourteenth Street which disgusted me much less than the others I had sampled.

The place was a four-story mansion of brownstone, dating apparently from the late ’forties,

[6]

and fitted with woodwork and marble whose stained and sullied splendor

[7]

argued a descent from high levels of tasteful opulence. In the rooms, large and lofty, and decorated with impossible paper and ridiculously ornate stucco cornices, there lingered a depressing mustiness and hint of obscure cookery; but the floors were clean, the linen tolerably regular,

[8]

and the hot water not too often cold or turned off, so that I came to regard it as at least a bearable place to hibernate till

[9]

one might really live again. The landlady, a slatternly, almost bearded Spanish woman named Herrero, did not annoy me with gossip or with criticisms

[10]

of the late-burning electric light in my third-floor

[11]

front hall room; and my fellow-lodgers were as quiet and uncommunicative as one might desire, being mostly Spaniards a little above the coarsest and crudest grade. Only the din of street cars in the thoroughfare below proved a serious annoyance.

[6]

and fitted with woodwork and marble whose stained and sullied splendor

[7]

argued a descent from high levels of tasteful opulence. In the rooms, large and lofty, and decorated with impossible paper and ridiculously ornate stucco cornices, there lingered a depressing mustiness and hint of obscure cookery; but the floors were clean, the linen tolerably regular,

[8]

and the hot water not too often cold or turned off, so that I came to regard it as at least a bearable place to hibernate till

[9]

one might really live again. The landlady, a slatternly, almost bearded Spanish woman named Herrero, did not annoy me with gossip or with criticisms

[10]

of the late-burning electric light in my third-floor

[11]

front hall room; and my fellow-lodgers were as quiet and uncommunicative as one might desire, being mostly Spaniards a little above the coarsest and crudest grade. Only the din of street cars in the thoroughfare below proved a serious annoyance.

I had been there about three weeks when the first odd incident occurred. One evening at about eight I heard a spattering on the floor and became suddenly aware that I had been smelling the pungent odour

[12]

of ammonia for some time. Looking about, I saw that the ceiling was wet and dripping; the soaking apparently proceeding from a corner on the side toward the street. Anxious to stop the matter at its source, I hastened to the basement to tell the landlady; and was assured by her that the trouble would quickly be set right.

[12]

of ammonia for some time. Looking about, I saw that the ceiling was wet and dripping; the soaking apparently proceeding from a corner on the side toward the street. Anxious to stop the matter at its source, I hastened to the basement to tell the landlady; and was assured by her that the trouble would quickly be set right.

“Doctair Muñoz,” she cried as she rushed upstairs ahead of me, “he have speel hees chemicals. He ees too seeck for doctair heemself—seecker and seecker all the time—but he weel not have no othair for help. He ees vairy queer in hees seeckness—all day he take funnee-smelling baths, and he cannot get excite or warm. All hees own housework he do—hees leetle room are full of bottles and machines, and he do not work as doctair. But

[13]

he was great once—my fathair in Barcelona have hear of heem—and only joost now he feex a

[14]

arm of the plumber that get hurt of sudden. He nevair go out, only on roof, and my boy Esteban

[15]

he breeng heem hees food and laundry and mediceens and chemicals. My Gawd,

[16]

the sal-ammoniac

[17]

that man use for

[18]

keep heem cool!”

[13]

he was great once—my fathair in Barcelona have hear of heem—and only joost now he feex a

[14]

arm of the plumber that get hurt of sudden. He nevair go out, only on roof, and my boy Esteban

[15]

he breeng heem hees food and laundry and mediceens and chemicals. My Gawd,

[16]

the sal-ammoniac

[17]

that man use for

[18]

keep heem cool!”

Mrs. Herrero disappeared up the staircase to the fourth floor, and I returned to my room. The ammonia ceased to drip, and as I cleaned up what had spilled and opened the window for air, I heard the landlady’s heavy footsteps above me. Dr. Muñoz I had never heard, save for certain sounds as of some gasoline-driven mechanism; since his step was soft and gentle. I wondered for a moment what the strange affliction of this man might be, and whether his obstinate refusal of outside aid were not the result of a rather baseless eccentricity. There is, I reflected tritely, an infinite deal of pathos in the state of an eminent person who has come down in the world.

I might never have known Dr. Muñoz had it not been for the heart attack that suddenly seized me one forenoon as I sat writing in my room. Physicians had told me of the danger of those spells, and I knew there was no time to be lost; so

[19]

remembering what the landlady had said about the invalid’s help of the injured workman, I dragged myself upstairs and knocked feebly at the door above mine. My knock was answered in good English by a curious voice some distance to the right, asking my name and business; and these things being stated, there came an opening of the door next to the one I had sought.

[19]

remembering what the landlady had said about the invalid’s help of the injured workman, I dragged myself upstairs and knocked feebly at the door above mine. My knock was answered in good English by a curious voice some distance to the right, asking my name and business; and these things being stated, there came an opening of the door next to the one I had sought.

A rush of cool air greeted me; and though the day was one of the hottest of late June, I shivered as I crossed the threshold into a large apartment whose rich and tasteful decoration surprised me in this nest of squalor and seediness. A folding couch now filled its diurnal role of sofa, and the mahogany furniture, sumptuous hangings, old paintings, and mellow bookshelves all bespoke a gentleman’s study rather than a boarding-house bedroom. I now saw that the hall room above mine—the “leetle room” of bottles and machines which Mrs. Herrero had mentioned—was merely the laboratory of the doctor; and that his main living quarters lay in the spacious adjoining room whose convenient alcoves and large contiguous bathroom permitted him to hide all dressers and obtrusive utilitarian devices. Dr. Muñoz, most certainly, was a man of birth, cultivation, and discrimination.

Other books

A New Resolution by Ceri Grenelle

Sight of Proteus by Charles Sheffield

Bobcat and Other Stories by Rebecca Lee

Galdoni by Cheree Alsop

She's Not There by Jennifer Finney Boylan

The Vampire Hunters (Book 2): Vampyrnomicon by Baker, Scott M.

Amy Phipps - Amanda Blakemore 01 - A Bazaar Murder by Amy Phipps

Snowy Christmas by Helen Scott Taylor

Mistake: A Bad Boy Stepbrother Romance by Lauren Landish

Japanese Portraits: Pictures of Different People by Donald Richie