Come and Take Them-eARC (17 page)

Read Come and Take Them-eARC Online

Authors: Tom Kratman

Tags: #Military, #Science Fiction, #General, #Action & Adventure, #Fiction

“We’re…waiting,” Minden gasped, “…for…”—gasp—“…the…”—gasp—“…explosion,” he finally managed to get out.

“Explosion? What explosion?!”

Without warning, Campbell and Top were rocked back over a meter, barely keeping their feet as a fifteen-pound satchel charge detonated about seventy-five meters to their right front.

Top was the first to recover his equilibrium. He made sure to tuck his stick back under his arm before speaking, “I see.

That

explosion. Carry on, Centurion.”

By the time Minden returned to his headquarters team, his junior centurion was already directing the assault.

Campbell’s ears were still ringing. Seventy-five meters away was just way too close to set off that large a blast without people being behind cover.

Or warned to cover their fucking ears at a minimum.

“An unusual case, Centurion Minden,” said Top.

“Unusual?” prodded Campbell.

“Oh, yes. He is one of only seven men in the legion that have served in three different armies; in his case the Castilian, the Sachsen, and ours. Two armies? No, that’s not unusual. We have Volgans, Southern Columbians, a few Secordians, Jagelonians…all kinds of Latins, Cochinese… Shitloads of refugees from other armies, other cultures. But three is quite rare. I expect him to go far.”

“Because he’s been in three armies?” asked Jan.

“No, ma’am,” Top replied. “Because he went looking for the right army and finally found it. Why, had it not been for us, he might have ended up with the Gauls. What a waste that would have been!”

* * *

The maniple called a halt about the time the sun went down. They were behind on sleep, and had some serious action planned for the following day. Better still, the mess folks had turned their normal rations into something more fully resembling a real meal.

Campbell and Hendryksen had been doing pretty well on their own side’s rations. After all, with about nine different cuisines, and about thirty-five different menus, to choose from, at least they weren’t bored. This was an artifact of having so many different detachments in the Tauran Union Security Force. Normally, a Tauran army had anywhere from two to eight different menus. Which was sheer hell if one had to live off them for any period of time.

That night Top and Campbell spoke further. Rather, she continued grilling him as she had been, which grilling he put up with and with good humor. He’d also invited her to share a meal of legionary rations. Since that, too, was a part of combat effectiveness, she’d agreed…as long as she was invited. She wasn’t about to overstay her welcome by asking.

Once she’d assented, Top made a signal to a private, two fingers held up. The private scurried off to the mess line, grabbed two metal trays, a fork and knife, and a couple of cups, then got in the line.

That’s the first thing I’ve seen that says they’re putting on any show for my benefit at all,

Jan thought.

And, under the circumstances—not knowing if I was willing to eat with them—it strikes as less a show than an effort at politeness and economy.

The private brought the two trays over, then passed them over carefully to avoid spilling the drinks. Jan sniffed and had to admit, “Smells…pretty good, Top.”

“Damned well better,” said the first centurion, “or I’ll have the cooks

cojones

to decorate my stick… Oh, sorry, ma’am.”

“I’ve heard the word, and in more than one language,” she answered. “Don’t sweat it.

“Something has been bugging me, though.”

“Yes?”

“I’ve been with your cohort now for a while. Why haven’t I seen any man have to eat the same thing twice?”

Legion rations were canned, as most armies’ had been until quite recently, but came in squad packs, something like Anglian rations did.

“I’ve eaten a lot of other folks’ rations,” Top said. “And I know something about this since it’s a half day’s training at the Centurion Candidate School.

“We just have a lot more menus than you do. Over seven hundred daily menus, to be exact…in theory. The real number is somewhat less because some things just don’t go well together. At any time there are something like forty-eight individual meal menus, with variables…starch, desert, vegetables. I say something like because they change them out, so there might be more than forty-eight in the system. Usually are, in fact.

“I think this is one area where

we

outdo everybody else. Still, you needn’t be ashamed.

Our

people are simpler, not so sophisticated…”

“You mean ‘spoiled.’” she said.

“I didn’t say that. But, since you did…Anyway, our legionaries just expect less. They’ll eat what is put in front of them. So the people who designed the ration system—I understand General Carrera took a personal hand in that, too; oh…and he taste tests every one—don’t have to worry so much about making meals that everyone will eat. Everyone will eat pretty much everything. It allows us more…latitude?…in planning meals. And we don’t try to worry about each individual meal being balanced; as long as the average is balanced. On the other side…it’s also kind of demoralizing, you know…when a soldier can tell what day it is by what he’s eating? That’s almost impossible with our rations.”

Illustrating the point somewhat, Top picked up his fork and dug in.

Jan dug in herself.

Well,

she thought,

at least Balboan cuisine didn’t start on a dare. Not bad, really.

She heard a series of harshly barked commands interspersed with thumps and pained grunts coming out of the jungle behind her. Setting her fork down she turned to look. Walking upright, stick under one arm, a tall and slender junior centurion, as black as the end caps to his stick, gave an order.

“Centurion, J.G., León,” Top volunteered. “A hard ass even by our standards.”

León gave another command. Four unfortunates arose from the ground, rushed forward, and flopped down.

“Tsk,” said Top. “How sad?”

León’s loudly voiced opinion was that it wasn’t sad and they were not unfortunate. “You lazy shits will do this to my utter satisfaction or your own death, whichever comes first. Again!”

“Who are they?” Jan asked in a hush.

“B team, Third Squad, Second Platoon,” Top said. “They’re short a man so it’s one reservist corporal and three militia privates. They got sloppy…yes, lazy, too, while the platoon had run through the range. Were too slow in their rushes. Maniple commander had assessed them as casualties, which—with other casualties—had caused the platoon to fail the mission even though they had taken the objective. So León’s going to fix it so they don’t get lazy again. Cause

his

platoon to exceed the standard for casualties, and fail? Make it so everybody had to do the problem again? Only right they suffer for it.”

At another of the junior centurion’s orders the four flung themselves to the rock-strewn ground. León gave them only a scant second’s breather before sending them off again.

The four boys had been doing short—three to five second—rushes, without a serious break and certainly without dinner, since well before sunset. They were cut and bruised from the many rocks that littered the ground. Jan turned away, embarrassed, as León smacked the corporal across the shoulder with his “stick.” “Maggot! This is how you lead my boys?”

A cook brought over two large mugs of coffee, handing one each to Jan and Top. Jan sniffed at hers as the first centurion offered simple, “Thanks.” One sip and Jan started to choke, much to Top’s amusement.

“What the hell is

in

this?” she demanded.

Top sipped and answered “My guess would be about two ounces of straight grain alcohol. But you’re a guest and we have some extra so yours may be a little stronger than that.

“It comes, canned, with the ration packs. Roughly two ounces per man per day. Sometimes we withhold it, for punishment…or to save for a special occasion. Although ordinarily the squad leader has the power to dispense or withhold the daily alcohol ration, in this case, because they all failed, the platoon won’t get any.”

“You aren’t afraid of one of them going wild; what with all this ammunition?”

Top quoted something he had heard the late Sergeant Major McNamara say at Centurion Candidate School. “‘You can

never

teach men not to drink. You

can

teach them to drink responsibly.’ We try to. Mostly, it works.”

As Campbell again sipped, more carefully, at her coffee, León’s voice, and slashing “stick,” cut the night. “

Gusanos! Maricones! Otra Vez!”

Worms! Fags! Again… And again. And yet again. The thuds of bruised and bleeding bodies, self-tortured, sounded faintly in the distance.

Chapter Sixteen

’Tis pleasant purchasing our fellow-creatures; And all are to be sold, if you consider Their passions, and are dext’rous; some by features Are brought up, others by a warlike leader; Some by a place—as tend their years or natures; The most by ready cash—but all have prices, From crowns to kicks, according to their vices.

—

Lord Byron

,

Don Juan (canto V, st. 27)

Teixeira Island, Lusitania, Tauran Union, Terra Nova.

The promise of limited rejuvenation hung in the air. Still, Marguerite couldn’t mention it openly; there were politicos and diplomats present who really were principled, who really thought they were working for mankind, not for themselves. This, of course, didn’t stop them from living pretty well as they worked for the betterment of mankind, but that made them only human.

Fortunately,

she thought,

there are also plenty of people here who are unprincipled, who know exactly what’s on offer and would gladly kill their mothers for the reward. Oh, we are so obviously of the same species…and I see my own government in proto form right here.

Marguerite had looked to ensure that her predecessor’s former occasional lover, Unni Wiglan, was not present.

I wonder if she figured out where one of the nukes she arranged to provide to Martin ended up. In any case, I’m glad she’s not very prominent anymore; the idea of increasing

her

lifespan is just too wrong on so many levels.

On the other hand, now that I think about it, it might be worth finding out, if possible, if she has guessed where the nuke for Hajar came from. If so, she’s got a very dangerous piece of information.

That’s for the future, though. For now I have other problems.

In one corner, over a table, Janier and the small staff cell he’d brought with him were arguing with half a dozen representatives of both Tauran Union and national ministries of defense over just how big the slice for Santa Josefina must be.

At least,

thought Marguerite,

they’re not still arguing over the

principle

of sending troops to guard Santa Josefina, just the numbers.

For the tenth or twentieth time, she once again looked over the force list Janier had given her.

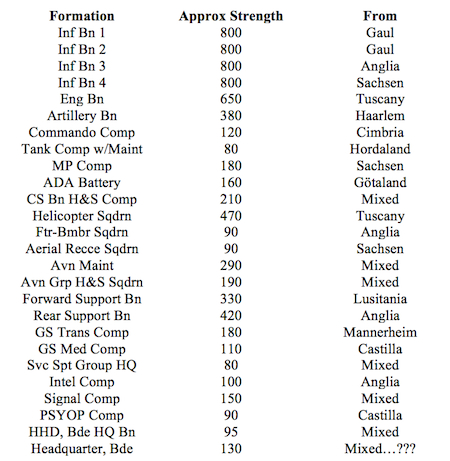

I think Janier’s got a defensible force package. Combat forces: Four light infantry battalions, one commando company or equivalent, one tank company. Combat support: One artillery battalion, one engineer battalion—clever bastard sold them on that one already with his “they will be invaluable for civic action and public works” routine—one MP company for route security and prisoner guard, and an air defense artillery battery. Aviation: A helicopter squadron, a fighter bomber squadron, and a recon squadron, with a maintenance squadron and a headquarters and support squadron. Headquarters and service support: One forward support battalion, one rear support battalion, plus medical and transportation companies extra. And a headquarters battalion with signal, PSYOP, and intelligence companies.

One of Janier’s underlings, a short and stocky type, running to fat, named Malcoeur, walked briskly over from where he’d been scribbling on an easel with butcher paper. “Madame Admiral,” he said, “the general could use a little moral support.”

Something in Malcoeur’s tone suggested that he’d be perfectly happy if Marguerite just let the general stew. She let that pass for the nonce. Folding the force list packet up and putting it away, she stood and walked to the corner table where Janier argued with the ministerial representatives.

“What seems to be the problem, General?” she asked of Janier.

The latter theatrically held clenched fist to forehead. “The world prepares to burn,” he said, full of self-righteous fury, “and these…these

people

argue over who is going to pay for the water.”

Thinking,

He’s a little too melodramatic to make it in the theater, but not bad for a military or naval officer,

Wallenstein raised a scornful eyebrow and glared at the assembled bureaucrats. “In all of my roughly

two hundred

years”—she emphasized the number, then paused to let that emphasized number sink in—“I have never seen such a shortsighted, narrow minded, group of… Oh,

words fail!

”

Maybe I should have petulantly stamped my foot. Or is the Gaul’s overacting affecting my judgment?

“Madame High Admiral,” said the middle aged representative of Tuscany, “our problem is that we have to go back to our masters in our own capitals and justify why we offered X, while Anglia or Gaul or Sachsen offered only Y. Ask them and they’ll tell you exactly the same things, only substituting their country for Tuscany.”

“And the perfidious Castilian,” said the Gallic representative, “offers nothing but some medicos and propagandists.”

“I told you before, gentlemen,” said the Castilian, “the defection of Colonel Muñoz-Infantes and his entire battalion to the Balboans has tied our hands. We cannot give a penny, we cannot offer so much as a round of ammunition, to anything that endangers our men there directly, even if they are defectors.” The Castilian glared at Janier and then at the other Gauls, in turn. “They should perhaps have realized that when they tried to have Muñoz-Infantes killed…and

failed

.”

“No more than arrested,” countered Janier. We would never have killed an allied officer.

“

Nobody

believes

that,

” said the Castilian.

Replied Janier, “I cannot be held responsible for the paranoid delusions of others.”

Of course, General,

thought Marguerite, looking directly at Janier,

you absolutely

did

intend that Muñoz-Infantes would be killed.

Well of course,

said Janier’s return glance.

I only look stupid and even then only when I drink. To excess.

“Who is offering what?” asked Wallenstein.

“The republic of Gaul,” said Janier, most self-righteously, “has offered two infantry battalions, a service support battalion, and a headquarters company with a brigadier general to command the force.”

“Funny,” said the Anglian representative, Mr. Crewe, short, plump, and clever-looking. “Funny how the bloody Gauls are always willing to provide a commander.”

“And Anglia has offered?” asked Marguerite.

“Ummm…one infantry battalion and…ummm…a brigadier to command.”

Janier laughed aloud, calling to the entire room, “Hypocrites. Oh, perfidious Anglia.”

Marguerite scanned over the assembling Taurans. “Will you accept,” she asked, “my judgment of who should command?”

“Somebody has to decide,” said Cimbria. “And we’ll never agree on our own. Madame High Admiral, will you

please

be the one to decide?”

This was greeted with murmurs of approval, generally, with only the Gauls and Anglians remaining silent. “Oh, all bloody right,” said Crewe, relenting.

Janier didn’t wait for the civilian from Gaul to say a word. “Gaul agrees,” he said, earning himself a glare from the civilian. “Malcoeur, show the high admiral what’s on offer.”

The aide went back to the butcher paper and flipped several sheets back. “Here, High Admiral.”

Wallenstein read:

“That,” pointed out Malcoeur, “is merely tentative, High Admiral. No one has yet definitively agreed to anything.”

“It’s heavy on multilingual people in a number of places,” added Janier; “some of the headquarters, the signal company, the intelligence company, and aviation maintenance and air operations support, especially. It’s unavoidable, really, with this many languages involved.”

“This isn’t entirely based on population or wealth or size of military, is it?” asked Marguerite.

“No, High Admiral,” Janier admitted. “Those were factors, of course, but one of the big drivers, as especially with Castile, is willingness.”

“High Admiral,” said the representative from Hordaland, “we can’t offer anything in good faith that our governments won’t, in good faith, honor.

“Will they honor that?” she asked, pointing at Malcoeur’s easel and butcher paper. “And the sticking point is who’s to be in charge?”

“Yes, High Admiral,” said all the representatives of the big four—Gaul, Anglia, Sachsen, and Tuscany—together.

“Will Anglia accept a Gallic commander?” she asked.

“Under no circumstances,” answered Crewe. “Been there. Done that. Didn’t like it the first time.”

She looked past Janier for the representative of the Republic of Gaul. “No Anglian commander,” he said, without being asked.

She looked for the Sachsen rep. Even before she found him both Gaul and Anglian said, “No, no Sachsen commander.”

“We’ve both been there before,” said the Gaul, “and we liked that even less.”

“Is there a brigadier or major general in the Tuscan army everyone could approve of?” she asked the Sachsen, who was surprisingly not very put out that the Gauls and Anglians had nixed a Sachsen general.

“Claudio Marciano,” the Sachsen said. “I think he’s retired now…”

“Semi,” said the Tuscan rep. “He’s working for the World League.”

“Available then?” Marguerite asked.

“The World League would be happy to send him to command this force,” said Mr. Villechaize, from the World League, “but for him to have command authority the Tuscans, or someone in the Tauran Union, would have to recommission him.”

“We could recall him to duty,” said the Tuscan.

“Objections, Anglia? Gaul?”

“Not really,” answered Crewe. After all,

Anybody but the bloody Frogs.

“None,” said Janier. After all,

At least Italian is a related tongue…and not English.

“Let’s call that settled then,” said Wallenstein. “That force list. The Tuscan in command, certainly for the first iteration. Now how do we transport them? And remember, there’s not a lot of time to waste here.”

* * *

In a private dining room she shared with the general, Marguerite rubbed at her temples.

There are some kinds of headaches even Old Earth medicine can’t do a thing about.

Janier clucked sympathetically.

“It comes with dealing with a certain kind of bureaucrat,” he said. “On the other hand, without your moral authority as the representative of Old Earth and commander of the Peace Fleet, we’d still be arguing, we’d have gotten nowhere, and my headache would be even worse than yours, I assure you.”

He didn’t mention the implicit major bribe. By common understanding that was an unmentionable.

He managed to raise a reluctant chuckle out of the high admiral. Sadly, the chuckle raised her pain level.

“Will the rest uphold their part of the bargain?” she asked through the curtain of her pain.

He nodded sagely. “I think so. After all, it’s not as if we’re trying to get them to, say, actually agree to and follow through on substantially larger defense budgets. The forces they’ve agreed to are already in existence and won’t cost more—rather less, actually—to maintain in Santa Josefina than in their home countries.”

“Does it leave you enough to reinforce the Transitway Area as we’ve discussed?”

“Yes, though if you think they whined and moaned about the less than eight thousand troops going to Santa Josefina, under Tuscan command, wait until they have to produce fifty thousand, plus another twenty in follow-on forces, under my command.” He hesitated, then reaching into a pocket said, “Oh, that reminds me.” He pulled a fax from the pocket and handed it over, but said what it was anyway. “The Republic of Gaul is promoting me to a rank commensurate with command of the corps I intend to raise in the Transitway Area.”

“Good,” she said, “because I can already hear the rest whining that you are too junior and using that as an excuse to withhold troops.”

“My thought, precisely, which is why I expended a few tokens to arrange the promotion.”

Again she laughed and again she winced. “Oh, we are so

obviously

the same species and culture.”

“Indeed?”

“Oh, I think so.”

“Old Earth must be a very fucked up place then.”

“In some ways, sure,” she admitted. “Where is that not true?”

“What—” The waiter’s knock on the door interrupted Janier in whatever he’d been about to ask.

“How do you think the other side is going to react to this?” she asked.

“Shock,” said Janier. “They’ve had the initiative for a while now, long enough to have gotten used to it. Even when they started to back off from their provocations, that was them exercising initiative they were sure was theirs, probably forever.

“This will be the first time in that same while that we’ve taken the initiative. That we’re taking it in a place they consider mostly theirs—a friend, a cultural ally, and a recruiting ground—is going to shock them silly.”

“What will they

do

though?” Wallenstein asked.

“Mobilize one of the two regiments they have near their eastern border with

Valle de las Lunas,

” Janier said, definitively. “I doubt they can keep both mobilized without wrecking the local economy. We can probably anticipate a border incident or two, but even if not those defensive preparations of theirs can easily be presented as offensive.

Then

I can start the provocations around the borders of the Transitway Area that, to date, my political masters have not permitted.”