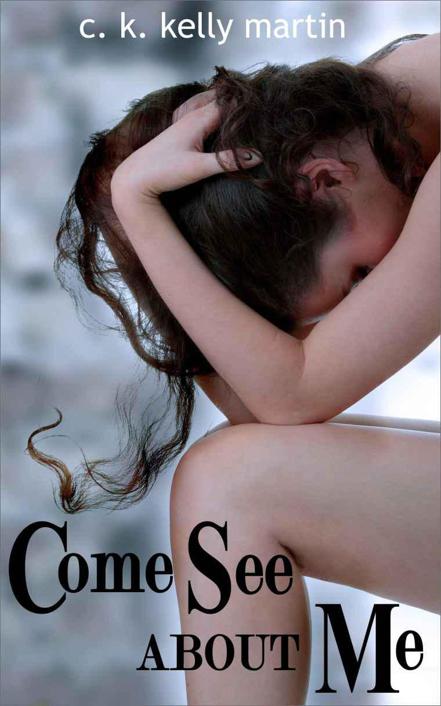

Come See About Me

Authors: C. K. Kelly Martin

also by C. K. Kelly Martin

I Know It’s Over

One Lonely Degree

The Lighter Side of Life and Death

My Beating Teenage Heart

Yesterday

This is a work of fiction. Names,

characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblances to actual persons,

living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright 2012 by Carolyn

Martin (C. K. Kelly Martin)

Jacket photograph: Stock footage

provided by BDS/Pond5.com

All rights reserved. This book

contains material protected under international copyright laws. Any

unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this

book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without express permission

from the author.

I can’t listen to music with

lyrics anymore. I can’t read more than a couple of sentences from a newspaper

or novel without losing focus. I’ve lost fifteen pounds since last January

because I forget to eat, and even when I remember, I don’t have much of an

appetite. The first thing I do when I get up these days is shuffle out of the

spare bedroom and into the bath because otherwise I’m liable to forget that

too. I drop my skinny white body into the empty tub and let the warm water fill

up around me so that Abigail, during the couple of weeks she spends here every

few months, won’t think she made a mistake in letting me stay and change her

mind.

I can’t have

that. I don’t want to go.

It was bad

enough having to leave the apartment Bastien and I shared in Toronto. I

should’ve figured out a way to stay and hang on to that little piece of the

life we had together, but I didn’t. I couldn’t focus enough to solve that

problem either.

So I’ve been

living in Oakville, at Abigail’s house, a fifteen-minute walk from the lake,

for just over two months now. She swooped in and saved me when I didn’t know

what to do—only that I didn’t want to fly home to B.C. and move back in with my

parents like they were convinced was best, and that I couldn’t humor any of my

Toronto friends who’d offered to squeeze me into their shared apartments/houses

either. People expect you to talk to them, even the ones who tell you they

understand. They want energy you don’t have. They want you to care about

something and I don’t.

Alone is what’s

easier. Everyone else would prefer that I pretend my life hasn’t been hollowed

out. They believe their expectations should carry some weight with me. Only

Bastien truly carries any weight and people try to use that fact against me too

and tell me what he would want for me. Some of the things they say about that

might be right, but since he’s not here he doesn’t get to decide how I should

handle his absence.

I dip my head

back into the bath water to rinse the conditioner from my hair. It’s always the

last thing I do before I pull the plug. I was never the kind of girl to devote

a lot of energy to my appearance, but I used to at least take the time to

properly rinse the conditioner out of my hair. I’m clean, though; presentable.

Abigail’s house is too—mainly because I’ve been living light. I never have

people over and have barely turned on the oven. My daily menu consists of

cereal, fruit, bread, and microwavable items like noodle bowls.

That considered,

my grocery bill shouldn’t be much more than a small domestic pet’s, but too

often I stop into the nearest corner store and stock up there. They don’t carry

bread or fruit but they have the other things, at inflated prices. When I do

make it all the way over to the grocery store or fruit market it’s actually

because of Armstrong. Hamsters need a small amount of fruit and vegetables

every day and no matter how I feel I can’t let anything happen to Armstrong. I

guess that means I care about something after all.

Taking care of

Armstrong is my biggest daily priority, and because hamsters are nocturnal, the

first time I look in on him he’s usually asleep, burrowed in his bedding or

occasionally, if I’ve forgotten to take it out, his wheel. If I leave it in

overnight he tends to run on it until he makes himself sick. Bastien was the

first one to notice that. One night he was camped out on the couch composing a

Chaucer essay for English class while I was fast asleep in the bedroom. The

noise from the spinning hamster wheel kept breaking his concentration, so

Bastien tugged on earphones and cranked up the tunes—classical music, which he

always used to say was the only kind of music he could listen to while working.

When he took off the earphones hours later the wheel was still squeaking away,

propelled by a worn-out-looking but obviously compulsive Armstrong.

It’s as though

he can’t help himself. He craves the wheel like some humans crave heroin or

sex. So we started rationing Armstrong’s wheel time for his own good, taking it

out before we went to sleep ourselves. Sometimes now I forget to take the wheel

out at night and wake up to the sound of Armstrong engaged in an endless

marathon. His cage is in the spare room with me because I don’t want Abigail to

feel like I’m taking over her house, but I don’t mind having him there anyway

because he reminds me of Bastien. Our landlord said no cats or dogs, but he

never said no hamsters and Bastien wanted a pet.

In the evening,

after Armstrong’s woken up and gorged himself on whatever’s in his food bowl,

I’ll replace his wheel for him and he’ll race around inside it like a junkie.

In the meantime I drag my comb through my hair and head for the kitchen. Just

coffee for now because I’m not hungry. I drink it with one sugar but no milk

because there isn’t any. I should go to the store today. Walk into town and hit

the fruit market.

First, I curl up

on the couch in front of the television and click on the remote. Abigail has a

really crappy cable package, which makes sense since she’s never here to watch

it. I didn’t used to watch much TV either, but now I need the background hum

and keep it on for the majority of the day. They say TV induces a trance state

and that the longer you watch the deeper the trance gets. I know it’s true

because I live that most days. Faces morph into other faces. Two women in

bridesmaid’s dresses screech at each other. Another woman is found dead in bed with

her bathrobe on backwards. Gordon Ramsey acts outraged and then makes crab

cakes. A taxi careens into the side of a van in the pouring rain. Doctor Phil

makes a tepid joke and waits for his studio audience to laugh.

Sometimes, when

I’ve had enough of that, I watch the news all day instead. Or sports. It could

be anything really. As long as it’s noise and moving pictures. Something to

park my skinny, white, freshly-rinsed body in front of.

Other days I

can’t stand the pixels and talking heads anymore and walk down to the lake to

watch geese and sailboats bob along the waves. An outdoor trance rather than an

indoor one.

About ten days

ago, two boys who appeared to be ten or eleven years old were throwing rocks at

the crowd of geese and ducks gathered in the water, and I envisioned lifting a

boulder effortlessly above my head, like Wonder Woman, hurling it in the boys’

direction and flattening them dead. Why not? Weren’t they demonstrating that

they’re destined to be serial killers or the future CEOs of soulless oil

companies? No respect, no conscience.

The trouble is

there are so many psychopathic kids (and parents) around that snuffing them out

could be Wonder Woman’s full-time job. In the old days I would have given the

boys the evil eye and told them to stop—or if Bastien was with me he’d have lit

into them before I’d even had a chance to open my mouth. He couldn’t stand to

see anything or anyone being hurt.

It’s hard to

rouse myself to say or do anything now that Bastien’s gone. It’s like fighting

my way through a fog or trying to scream in one of those dreams where it’s

struggle enough to whisper. So I didn’t say a word to them, just hated the boys

silently from within my impermeable fog.

As it turned

out, I wasn’t the only one who disapproved. A woman clutching hands with a

little girl in a sailor hat crossed towards the boys and said, “Hey there, stop

bothering the birds, guys.”

Her tone was

dismay mingled with impatience and the boys’ stunned glares made it clear she

was a stranger to them. “You can’t tell us what to do,” the shorter one with

the pinched face complained.

The woman was

even more taken aback than the boys had been seconds earlier, and in the silent

pause between them I broke through my murk with an unexpected flash of energy,

shouting, from my place on the boulder fifteen feet behind them, “Do your

parents let you throw rocks at birds?”

The taller boy’s

head sagged on his shoulders. He glanced guardedly at his friend as if to say,

let’s

go

. They dropped the rocks clenched in their fists and headed away from the

water and up to the grass. The little girl with the sailor hat turned to stare

at the geese and ducks while her mother and I swapped looks of solidarity.

Who needs Wonder

Woman? My lips stuck to my front teeth as I began to smile, but the woman’s

gaze had already shifted towards the lake.

Today I don’t

want to deal with kids throwing rocks at geese, but since I have to venture

further than the corner store I know I’ll end up at the lake. Once I’m far

enough from Abigail’s house the water has a habit of pulling me towards it,

like it wants me in its orbit.

When you don’t

have a car and don’t live in Toronto anymore, the distance between places

proves much longer than you’d ever realized, but Abigail’s Oakville

neighborhood is a pleasant place to walk: well-landscaped yards attached to

equally picturesque houses. There’s little traffic and little noise but lots of

money and political influence. In an alternate life I might want to settle down

here with Bastien in our late twenties, have the kids I’d never really stopped

to think about before Bastien died because the future felt both distant and so

certain that it didn’t seem to require any consideration.

I force myself

to turn off the TV, blow dry my hair and pull on a rumpled pair of jeans and

pink T-shirt. As soon as I get outdoors I’m reminded, by the strength of an

early September sun which feels more like August, that I should buy sunscreen.

My nose is still peeling from my last burn. It doesn’t matter except that when

Abigail gets here next week I want her to believe I’m keeping my head above

water enough for this arrangement to be a good idea. For that, I should look

the part. In control of basic health and hygiene.