Come to the Edge: A Memoir (5 page)

Read Come to the Edge: A Memoir Online

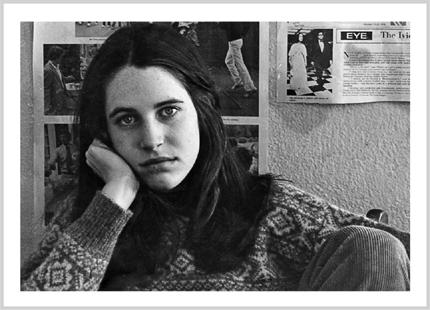

Authors: Christina Haag

Tags: #Social Science, #Popular Culture, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #United States, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography, #Television actors and actresses, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

Waiting

The meeting of two personalities is like the

contact of two chemical substances: if there is

any reaction, both are transformed.

—

CARL JUNG

I

n high school, we run in packs. It was no different in New York City in the mid-1970s at elite private schools such as Collegiate, Brearley, Dalton, Trinity, and Spence. We roamed the streets of Park and Fifth and ventured deep into the crevices of Central Park. We piled into Checker cabs, six or seven of us, or took the subway to Astor Place to wander the gridless Greenwich Village streets, untouched by designer outposts. SoHo was deserted; Little Italy was Italian; thrift shops were thrift, not “vintage.” We passed the Bottom Line and Free Being Records on the way to Caffè Dante or Washington Square Park. The subway, green and tattooed with the tags of graffiti masters, rattled and rolled. We stood at the front of the first car, window down, the rush of speed on bright faces.

Stone chess tables at Carl Schurz Park, the Burger Joint on Broadway, coffee shops near our schools, wisteria arbors behind the Bandshell, Alice in Wonderland, the winged angel of Bethesda Fountain, the boat pond, Belvedere Castle, and the long even steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—these we made ours.

“Later at Alice.”

“Catch you at the Met.”

It was all about meeting. That’s when the magic happened.

It’s the weekend, and in that narrow Upper East Side hub, we’re looking for apartments devoid of parents. Some are done up like Versailles, with gold accents, mirrored hallways, paintings glowing under their very own lamps, and Nat Shermans, like pastel candies, artfully fanned in small china cups. Others are more restrained—pale sofas, family pictures framed in silver, and everywhere the smell of soap. On the West Side, ornate gothic caverns rise, the stone dark with soot. And the buildings have names: the Kenilworth, the Beresford, the El Dorado. The real estate boom of the late eighties hasn’t happened yet, and the West Side lacks the spit and polish of the East Side. It’s dirtier, more dangerous, exotic. Often we head farther east or north, to smaller apartments without doormen—or with doormen whose uniforms fit more loosely—apartments of friends whose parents are not titans of industry or scions of inherited wealth, but schoolteachers, designers, artists, editors, or scientists.

We do our homework and we hang out. We smoke Marlboro Lights and we smoke pot. We lie about where we are going. We have crushes on boys we do not know but talk about incessantly. We are juvenile and we are jaded. We are insecure and we are worldly. With our friends as mirrors, we slip on identities like wispy summer dresses and just as easily toss them aside. Like teenagers everywhere, we are trying to find out who we are. Only we are doing it in a city that in 1975 has been almost felled by a fiscal crisis, where police and social services have been cut drastically, and homicide and muggings are rampant. Despite this, it is a city that knows itself to be the center of the world, the matrix where art and commerce thrive and power and excellence are de rigueur. This city. Ours. We can feel its promise; it’s there beneath our feet. A shallow beat in dark asphalt.

In 1974, I left the Convent of the Sacred Heart and its gray wool uniforms for Brearley. Although Sacred Heart went through twelfth grade, I wanted a change. Many girls in my class left that year. Some ventured as far as Spence across the street or Nightingale-Bamford around the corner. Some left the city entirely for boarding school. But I wanted to stay in New York, and my heart was set on the girls’ school in a ten-story building by the East River. One of the most competitive schools in the city, Brearley at that time resembled a prison and bristled with excitement. Caroline Kennedy had transferred there as well, but by the time I arrived, she had already left for boarding school. I didn’t know it then, but my world was edging closer to John’s.

“The Brearley,” as it is known, may have lacked the poetry of the Otto Kahn mansion, but it had a major plus: no uniforms. The younger girls ran around in navy jumpers, with bloomers for gym, but there was no dress code in high school. The feel was more bluestocking than deb, and although there were pockets of Brooks Brothers and smatterings of Fiorucci and Cacharel, the standard fare was tattered jeans. It was something I looked forward to.

The summer before ninth grade, a letter in the school’s signature shrunken envelope arrived. Inside, I was both welcomed to New Girl Orientation and asked to choose an elective. Music, dance, drama, and art were stacked one under the other. Next to each, a miniature red box. Mark one, the letter instructed. I was stunned. To my mind, they were inextricable from one another, part of one whole—what I loved best and far from optional. I stared at the word “elective” for a long time. Then I picked up my pencil and, with something akin to pain, checked drama.

Whereas Sacred Heart classmates were cruel behind your back, Brearley girls were more direct. They said what they meant. Opinion and curiosity thrived, and our class took it to the extreme. In an empty locker on the fifth floor, we kept a stash of racy books, calling it our pornographic library and even issuing library cards. Being Brearley, the smut was classic—along the lines of

Fanny Hill, The Story of O

, and Anaïs Nin’s

A Spy in the House of Love—

and we devoured each behind folders during chorus, until a zealous math teacher ratted us out.

Drama was taught by Beryl Durham. Small, muscular, and Welsh, she had silver hair that ran the length of her back and a face in constant rapture. She told us tales of Julian Beck and the Living Theatre, and of her friends “Larry” Olivier and Vivien Leigh. When goaded, she divulged that sex was just like strawberry ice cream—an improvement, at least, over the Sacred Heart nurse’s “like scratching an itch.” We worked on Elmer Rice’s

Street Scene

that year and a bad play by Giraudoux in which the tall girls played men and I was the heroine. For most, drama class was time to goof off, gossip, get Beryl to tell her stories and then make fun of her—anything but the embarrassing prospect of pretending to be someone else. But I was a fourteen-year-old who could not wait to lose herself in make-believe. In me, Beryl saw one of her own. Before classes ended for the term, she took me aside behind the heavy curtain in the auditorium. She was retiring at the end of the year. “You won’t get what you need here,” she said, her voice raspy and certain, her witch eyes wavering from blue to white. I nodded gravely, but before I turned to go, she pressed a small piece of paper into my hand. On it were the words

HB Studio

and an address on Bank Street.

My best friend in ninth grade was more experienced than I was. She took me under her wing, told me whose parents were famous and why, which girls were Legacy, and what the Social Register was. Most important, she made sure I never walked up Eighty-fourth Street to the two-block no-man’s-land ruled by neighborhood toughs. Chapin and Brearley had addresses on East End Avenue’s thin strip of privilege, but the half block west into old Yorkville was iffy. The toughs were just kids, really—kids who sat on stoops, who had knives, and whose favorite pastime was scaring nubile private school girls. “Why can’t the police stop them?” I asked her. We were huddled at the corner of Eighty-fifth Street. I was blocking the wind that tore down East End from the river so that she could light her cigarette. She shrugged. “It’s their turf. Besides, the fathers are all cops.”

My friend went everywhere on her bike, dodging traffic in a faded jean jacket, her stick-straight pale hair flying behind. She lived in a town house off Madison Avenue, and her parents were divorced. We’d sit on her bed after school and talk about boys. I’d never been kissed, and she promised to tell me the secret of kissing, but only if I was her slave for the year. She knew John. He went to Collegiate, the boys’ school across the park and brother school to ours. He’d been to a party at her house the year before and had left a black leather ski glove, which she kept hostage on her dresser. Part of learning the secret meant listening to her go on about how cute he was and how she would become Mrs. JFK Jr. Sometimes when she passed notes to me during Spanish class, she signed them that way as a joke.

At the end of ninth grade, the secret was revealed.

“Imitate what the boy does.”

“That’s it?” I said, my eyes widening.

“That’s it,” she said, tilting her chin and blowing a flawless smoke ring in my face.

By the next fall, I had been kissed, and that November one of the cool guys from Collegiate asked me out, although we never called it that. He and his friends were known as “the Boys” and they had nicknames that rang like handles: Sito, Wilstone, Johnson, Doc, Duke, Mayor, Hollywood, Clurm, Ace. He came with three of them to pick me up. All had long hair and puffy down jackets, and he whirled a red Frisbee upside down on his finger, mesmerizing my seven-year-old brother, who showed an excitement I tried to hide. “We’re going to Kennedy’s,” the whirler told my parents. “His mother’s home.” I kissed my father and promised to be home by eleven. I had never been to Kennedy’s before.

We walked up Park to 1040 Fifth Avenue, and when Lenox Hill dipped and flattened, they spread out—one across the street, another behind me, the one they called Sito short-stopping the divider—and they tossed the Frisbee across the wide avenue as we went. The boy I liked took my hand. It was cold that night, and soon the holiday trees would go up on the center islands that stretched north from the Pan Am Building all the way to Ninety-sixth Street. The sidewalk sparkled, the streetlamps catching bits of silver mica buried in the cement.

The elevator at 1040 opened onto a private foyer. There was a huge gilt mirror and the smell of paperwhites. The front door was unlocked, the rooms dark, and Kennedy’s mother wasn’t home. I followed them to the dining room, where girls from other schools—Spence and Nightingale and one in baggy corduroy from Lenox—lounged by a table near an Oriental screen. Some smoked. The boys stayed close to the open window, stepping on the drapes and making noise, and we watched as they lobbed water balloons and paper towels stuffed with Noxzema fifteen stories down to splat on the sidewalk below. They howled when they nicked someone. “Score!” they’d shout.

One boy was especially keen. He darted back and forth, cracking himself up. Skinny, his hair in his face, he seemed younger than the rest. And he was

really

into throwing those Noxzema bombs. “Nice one, Kennedy!” they’d yell. And if he seemed younger, it was because his birthday was at the end of November and he was still fourteen. But I wasn’t looking at him that night. I was watching the one I had come with. I had forgotten about the boy from the barbershop.

A group of us hung out that winter and spring. There were rumors that John liked a girl at Spence, but when he was with us, he was alone—a follower, under the tutelage of the older boys. We went to parties en masse, to sweet sixteens at Doubles, and to Trader Vic’s on someone’s father’s charge. We tumbled out of the Plaza with gardenias from the Scorpion Bowls tucked in our hair and continued on to Malkan’s, the East Side kiddie bar before Dorrian’s caught on. We trolled Central Park at all hours, slipping through the Ramble, a wooded section where muggings and beatings were frequent. In 1978, the year we graduated, members of the 84th Street Gang also ventured there and, armed with baseball bats and a couch leg, savagely attacked six men they believed to be gay. This time their fathers could not protect them, and they were arrested and jailed.

We felt safe those nights in the park, the Secret Service trailing behind us at a respectable distance. John’s mother insisted that they be invisible, and they almost were. But we always knew they were there. They had our backs. Or, rather, John’s. And we’d wander off trails on moonless nights, clogs and sneakers stomping dead leaves, the glow of a joint drifting backward like a firefly in the darkness. Invincible, fifteen, and jazzed by the spark of danger.

Years later, after his plane went down, I thought of the sense of safety I’d always felt with him. Where had it come from? It was instinctual, I knew that. Like the clarity of faith the nuns possessed and tried to drum into me. Was it something in him, I wondered, his fearlessness rubbing off, the strength of his life force so strong that I believed nothing would happen to me if I was with him? Or was it the memory of those nights when we were young, sticks snapping underfoot, watching our breath go white, and knowing that unseen men with badges and guns kept us safe in the center of harm.

One night toward spring, John met us in the lobby at 1040, and we ambled down to the Met for Frisbee golf. The fountains were drained, and there was no one around, just the smooth stretch of cement lit by streetlamps. But that night, the 84th Street Gang had come west of their territory. They cornered us and we scattered. Some slipped across to the awning of the Stanhope. Others ran up the museum steps and hid in the alcoves behind the columns. I ducked behind the nearest car next to the handsome boy we called Doc. He was scared and kept smiling at me.

“Eighty-fourth Street,” he mouthed, his eyes huge. “They

have

the Frisbee.”

I peered around the bumper. Two of our own were there, demanding the Frisbee back. John was one of them.

“What are they doing, they’re crazy,” I hissed.

“It’s not even their disc!” Doc agreed.

We heard voices rise, then—a flash of silver as the biggest one started forward and began to swing a large metal bar dressed in chains. Just as swiftly, from the other side of Fifth, two Secret Service men jumped from the shadows, flipped their badges, and the Frisbee was ours. As they trudged back to York Avenue, the 84th Street boys must have scratched their heads.

“Do you think they know?” I asked.

“Know what?” Doc said.

“That it was John. Do you think they’re talking about it now? The night we were busted by the Secret Service for stealing John Kennedy’s Frisbee. I mean, how often does

that

happen?”

Doc stood up by the car and dusted himself off. “Nah.” He thought for a second and began to chuckle. “But I sure hope Mrs. O doesn’t find out about this!”

I found the piece of paper Beryl Durham had given me in my ballerina music box under loose change and hair ties, and that spring I enrolled in Basic Technique for Acting at HB Studio. On Saturday mornings, I trekked to the Village, and as soon as I reached the top of the subway steps on West Twelfth Street, I took a deep breath. Unlike the tidy, canyoned avenues uptown, buildings here were low-slung, and I could see the sky. It felt like home.