Come Twilight (27 page)

In January, one traveler arrived from the east, a weaver looking for work. He has put himself to work here, making cloth in exchange for a place to sleep and meals to eat. He has shown no inclination to leave this place, and has spoken of neither father nor son. His name is Sunna, and he claims to have come from Corduba in his youth. Whatever the truth may be, he has made excellent cloth for us, and so we are inclined to keep him here with us if he is willing to remain.

In February, the first travelers came from the south-west—pilgrims bound for Roma. They were twelve in number, to honor the Apostles. They told of floods at Caesaraugusta and Osca.

In February, a severe storm struck on the 13

th

day, lasting for the next three, and once again, this place and the pass it guards were cut off

from the world. When the storm was over, the road was once again impassable for many days.

In February, the one-eyed ewe delivered a still-born lamb, much too early. The ewe was butchered and her flesh roasted. Her fleece has been made into saddle-pads and caps.

In March, a mountain cat attacked our flock of goats, killing a nanny and her twin kids. Men were dispatched to kill the cat, but were unable to locate the animal in the crags and the snow. Guards have been posted around the flocks to prevent any more slaughter.

In March, two men came from the south-west, with two horses and a mule, which bore three chests on its saddle. They were bound for Tolosa, and were coming from the mountains above Osca. They were not Greeks, nor Arabs, although one man claimed to be from Gades. As they carried only such weapons as a prudent traveler has with him, they were allowed to continue on.

In March, three widows from Aqua Sulla arrived from the east, bearing holy relics for the Episcus of Caesaraugusta, which they had vowed on their husbands’ graves to see placed in the hands of the holy Episcus.

In March, a company of peasants brought two cartloads of cheese and bacon to us, as is their duty of old. Rations were changed and the garrison is once again eating like fighting men.

This concludes our account of activities at Sancta Gratia, the which we submit with our earnest prayers that you may be honored and praised for your excellence, and that you will always be deserving of such distinction. May your sons thrive and bring glory to your House. May you be spared misfortune. May you never flag in your strength or your purpose. May you please men and God in all things.

Sartrium Braulio

by the scribe Ildefonsus

at Sancta Gratia, monastery and fortress

C

HIMENAE

T

ext of a dispatch presented to Numair ibn Isffah ibn Musa from Timuz ibn Musa ibn Maliq.

In the name of Allah the All-Merciful, I, Timuz ibn Musa ibn Maliq, send this account and petition to you, my illustrious nephew, and inform you that a similar account will be provided to your august father, may Allah show him many years of fortunate life.

The slave San-Ragoz, who was a gift to you from the Emir, your most honored father, has truly escaped, although I have been unable to determine who helped him in this; as it stands now, this misfortune has brought much consternation to your soldiers, particularly those guarding your household, for it has been determined that San-Ragoz departed from his cell, apparently through the window, as one of the bars is missing. It is as yet unknown if anyone assisted him in his escape, although it is unlikely that anyone would be so reckless as to assist your slave in such an enterprise. The window is more than two full stories above the courtyard, so any fall from such a height should have injured—if not broken—his legs, making flight impossible, but there is no indication this has happened. The gate to the courtyard remains closed, so I must conclude that either he scaled the wall, or he found another means to leave the courtyard without alerting any of the guards, which leads me to suppose he was aided in his endeavor. I believe he must have disguised himself and passed out with others departing from this holding around midnight, but I have no proof of it. To determine the truth of this, I have put a dozen of your personal guard to the work of examining all those who were recorded to have left through the gates after sundown.

I must tell you, my nephew, that I disapprove of your intention to make San-Ragoz your personal physician and to blind him so that he might tend to your women without shame. Most particularly, I tell you again that a man who works only at night is a dangerous man to your women; had he not his remarkable gift, I would advise you to kill him and save yourself from danger. But San-Ragoz has saved men others could not. It is not for you to send such a one as San-Ragoz to tend your wives and concubines. Your father, my brother, had no such intention when he sent this slave to you, as you are well-aware. San-Ragoz is known to be an accomplished physician, and such skills as he possesses are too valuable to waste on women, and so you will realize if you submit your will to Allah. You have many soldiers who require treatment for injuries and ills, and who have much greater call upon such a man as this slave than any of your women; it is fitting that you assign any man of such ability to your soldiers, who advance our faith and protect your family as no woman could. If it is Allah’s Will that this San-Ragoz remain uncaptured, you may take it as an indication your intentions were contrary to the Will of Allah, which does not become a true follower of the Prophet.

In these days since we have come to this city of Karmona, we have had to maintain our authority with the might of our soldiers and the favor of Allah. To deprive your men of San-Ragoz as a physician in order to have a slave for your women you show that you are not as devoted to the glory of our cause as you have claimed to be. You have sworn an oath to advance the green banner until it is seen throughout the world, and all follow the One True Faith. Any act of yours that impedes this is an abjuration of your oath, and unworthy of you, or your father, my brother, to whom you owe all your allegiance and your dedication, in the name of Allah.

Your soldiers have been told to hunt down San-Ragoz and to return him to you, and insofar as they act as Allah Wills, it shall be done, and the slave shall bow to you again. Your soldiers are sworn to you, and they will not fail you, so long as it is the Will of Allah that they succeed. I have no doubt that they are capable of the task you set them. But if you then continue with your plan and have him blinded, I will no longer stand with your troops on your behalf, nor will I do anything to protect you in any regard, for you will have shown yourself to be beneath my respect, and therefore of no consequence to me. If your father, the Emir—may Allah give him laudable years and many praise-worthy sons—should chastise me for this, I am willing to pay whatever price he demands of me, as is my duty and his right. Yet I warn you again: I will not and cannot support your wanton disregard for the good of your soldiers for nothing more than your women.

I have offered money for any information about this San-Ragoz and I will act upon anything I learn that will lead to his recapture. He has only been gone for two days and a night, and there is no report that he has been able to leave the city. I do not anticipate that this slave can go far, for his branded shoulder will surely be noticed, as is the brand on all slaves. It will not be many days before I bring San-Ragoz to you, and when I do, I ask that you reconsider your decision, and turn the slave to the tasks for which your father sent him to you: the care of your soldiers. Should you fail to do this, you know from this what I pledge to do. You must not doubt my purpose, for it is as firm as my adherence to the cause of the Prophet, and as the two are closely tied together, I will see that your father’s intentions are served before your whim. You may defy me—you have surely done so in the past—but I beg you to reflect before you do so in this instance that it is not only your uncle and your father you betray if you do not release the slave San-Ragoz to me for the care of your soldiers, it is the battle for the souls of Islam that you forsake by depriving your men of the medicinal knowledge of this San-Ragoz. What can such treason bring you but disgrace in this life and perpetual darkness after death?

To this I set my hand in Radjab of the year 103 of the Hegira.

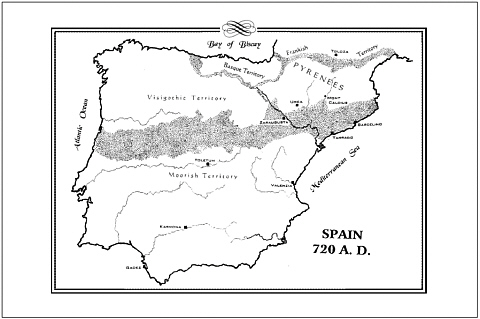

Now that it was dusk, he could move again; he had hidden all day, lying in the stupor that sunlight imposed upon him when he had no access to his native earth. San-Ragoz emerged from his hiding-place in the corner of the abandoned Roman cemetery where even the new spring flowers had an air of decay and neglect to them; he made his way past the ancient tombs with care, to emerge in the Old Merchants’ Quarter. He was relieved that he still wore his black Byzantine dalmatica and black Persian kandys with black embroidery accents at neck and hem, for although they marked him as a foreigner, they also concealed him. The fading light had driven many of the residents indoors, away from the patrols of Umayyad soldiers with their lances and scimitars and whips. Concentrating intently, San-Ragoz kept alert to the approach of anyone still on the streets. Keeping to the narrowest of alleys and the darkest of paths, he took a circuitous route to the Byzantine Monastery of the Assumption, a squat, ancient building near the Eastern Gate of the city he still thought of as Corduba.

From the inside the stone walls came the drone of Greek chanting; San-Ragoz sank into the shadows of the short transept and waited for the evening prayers to end and the monks to retire to their dormitory. He reckoned these monks would leave one of their fellows in the chapel to guard the altar-flame, and all the rest would go off to pray and sleep, as Greek monks did. Their repetitive text and monotonous droning proved calming and he began to relax for the first time since he escaped the palace of the Emir’s son. A pang of memory filled his thoughts with Charis and Cyprus, and his abduction to Tunis, followed by his sale into slavery; the enormity of his loss might have thrown him into melancholy but he forced such thoughts away: time enough for such recollection when he was out of Corduba—and to be out of Corduba he would have to achieve his goal here at the monastery. His opportunity would be brief, but he was determined to make the most of it, for if he could secure one of the habits, he could leave the city as a penitent before morning—not even the guards of the Emir’s son stopped devout Christians in the practice of their faith.

The moon had risen by the time San-Ragoz slipped into the monastery and made his way toward the dormitory. He moved with unusual swiftness and so silently that no one heard him pass, or if they did, attributed it to the whispers of dreams. At the entrance to the dormitory corridor he paused, taking stock of his surroundings; there were only three oil lamps burning from one end of the hall to another, a reminder of the Trinity. What little illumination each shed was only enough to magnify the darkness beyond it. For San-Ragoz, this presented little trouble: he could see almost as well in the dark as he did in daylight, and just now night was his ally. Recalling other monasteries he had seen, he assessed the few, spartan furnishings, hoping to choose the one most likely to contain what he sought. Finally he made his way to the large chest in the alcove at the head of the corridor. He opened this with care and was rewarded with a stack of rough-woven, darkcolored dalmaticas that served as habits for the monks. Very carefully he took one from the middle of the stack and arranged the remaining garments so that no sign of any disturbance was noticeable. He worked as rapidly as he could, knowing that he risked discovery if he brought attention to himself.

As he was about to step back into the night, he heard a cough behind him; he froze.

One of the monks was making his way along the corridor, one hand extended to touch the rough stones of the wall.