Command and Control (17 page)

Read Command and Control Online

Authors: Eric Schlosser

By the second year of the Clinton administration, most of the enthusiasm and idealism was gone. Personal differences, political disputes, and feelings of betrayal had led two of the Three Beards to quit. Industry groups worked hard to block or dilute many of Clinton's reforms, and the governor's willingness to compromise alienated many of his allies. Instead of subsidizing road construction with higher taxes on the use of heavy trucksâa move opposed by the state's trucking companies and poultry firmsâClinton agreed to raise the taxes paid by the owners of old pickup trucks and cars. The lofty rhetoric and grand ambitions of the young governor lost much of their appeal, once people realized they'd have to pay more to renew their license plates. During the spring of 1980, a series of tornadoes struck Arkansas. During the summer, the state was hit by a heat wave and the worst drought in half a century. Hundreds of forest fires burned. Cuban refugees, detained by the federal government at an Army base in the state, started a riot. They tried to escape from the base and fought a brief skirmish with the Arkansas National Guard, terrifying residents in the nearby town of Barling. Each new day seemed to bring another crisis or a natural disaster.

Having gained almost two thirds of the popular vote in 1978, Bill

Clinton now faced a tough campaign for reelection, confronting not only the anger and frustration in his own state but also the conservative tide rising across the United States. Frank White, the Republican candidate for governor, was strongly backed by the religious right and many of the industry groups that Clinton had antagonized. The White campaign embraced the candidacy of Ronald Reagan, attacked Clinton for having close ties to Jimmy Carter, ran ads that featured dark-skinned Cubans rioting on the road to Barling, raised questions about all the longhairs from out of state who seemed to be running Arkansas, and criticized the governor's wife, Hillary Rodham, for being a feminist who refused to take her husband's name.

While Lee Epperson, director of the Office of Emergency Services, tried to find out what was happening at the Titan II site in Damascus, Governor Clinton spent the evening in Hot Springs. The state's Democratic convention was about to open there, and Vice President Walter Mondale would be arriving in the morning to attend it. Hillary Rodham remained in Little Rock, where she planned to spend the weekend at the governor's mansion with their seven-month-old daughter, Chelsea.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

J

EFF

K

ENNEDY

WANTED

a closer look at the white cloud drifting about two hundred feet away, on the other side of the perimeter fence.

“

Captain Mazzaro, we have to get that propane tank off the complex,” Kennedy said. A fire in the silo could ignite it. The tank was sitting on the hardstand, near the exhaust vents, attached to a pickup truck. Kennedy suggested that they enter the complex and drive the tank out of there.

Mazzaro thought that sounded like a good idea. But he and Childers had no desire to do it. They hadn't brought their gas masks, and the idea of running through clouds of fuel vapor without the masks didn't sound appealing. Kennedy and Powell seemed eager to move the tank; Mazzaro told them to go ahead. He and Childers would wait by the fence.

The gate was still locked, and so Kennedy and Powell had to leave the access road, circle the complex, and enter through the breakaway section of the fence. Kennedy wore combat boots and fatigues. Powell was still in

long johns and the black vinyl boots from his RFHCO. They walked along the chain-link fence, looking for the gap.

Kennedy had no intention of moving the propane tank. He planned to enter the underground control center and get the latest pressure readings from the stage 1 tanks. That was crucial information. In order to save the missile, they had to know what was going on inside it. Mazzaro wouldn't have liked the plan, and that's why Kennedy didn't tell him about it. The point was to avert a disaster. “If Mazzaro hadn't abandoned the control center,” Kennedy thought, “I wouldn't need to be doing this.”

Fuel vapors swirled above the access portal, but the escape hatch looked clear. Kennedy ran for it, with Powell a few steps behind. During all the visits that Kennedy had made to Titan II complexes over the years, to fix one thing or another, he'd never been inside the escape hatch. The metal grate had been removed topside, and the two men climbed inside the air shaft, Kennedy going first.

“

Stay here,” Kennedy said.

“Hell no,” Powell replied.

It'll be safer if I go down there alone, Kennedy said. I can get out of there quicker.

“

I'll give you three minutesâand then I'm coming down.”

Kennedy climbed down the ladder wearing his gas mask, then crawled through the narrow steel tunnel. He felt confident that the blast doors were sealed tight and that the control center hadn't been contaminated. But he didn't want to stay down there too long. The air in level 3 seemed clear, and the lights were still on. He got out of the escape hatch and ran up the stairs. Everything looked good; there was no sign that blast door 8 had been breached. Kennedy sat at the launch commander's console and pushed the buttons on the PTPMU. As the tank pressures flashed, he recorded them on a piece of paper.

“We're in some serious shit,” Kennedy thought.

The pressure in the stage 1 oxidizer tank had risen to 29.6 psi. It was never supposed to exceed 17 psi. And the burst disk atop the tank was designed to pop at 50 psi. If the tank hadn't already ruptured by then, the

burst disk would act like a safety valve and release oxidizer into the silo, relieving some of the pressure. Normally, that would be a good thing, but at the moment there were thousands of gallons of fuel in the silo.

The pressure in the stage 1 fuel tank had dropped to â2 psi. Kennedy had been told that the tank would probably rupture once it reached between â2 and â3. He was surprised that the pressure had fallen so much in the past hour.

I'm not even wearing a watch, Powell realized, moments after Kennedy disappeared down the hatch. After counting the seconds for a while, Powell figured that three minutes had passed. He climbed down the ladder to find Kennedy, made it about halfway, and then heard Kennedy yell, “

There's not enough room for two people!” Kennedy was quickly climbing back up.

“Oh, God,” Powell said, after hearing the latest tank pressures. They got out of the escape hatch, left the complex through the breakaway fence, and made their way back to the gate.

Kennedy told Mazzaro that they couldn't move the propane tankâand nothing more. The four of them walked down the access road to Highway 65. Colonel Morris was sitting in a pickup truck beside the road. Kennedy called him over and took him aside.

“

Sir, this is what the tank readings are,” Kennedy said.

Morris asked, “

Where in hell did you get those?”

Kennedy told him about entering the control center. The situation was urgent. They needed to do something about the missile, immediately.

Morris was glad to have the new readings but upset about what Kennedy had just done.

Something has to be done, and right away, Kennedy said. Earlier in the evening, he'd thought that the tank pressures would stabilize, but they hadn't. He explained to Morris how precarious things had become. There was a major fuel leak, not a fireâand the stage 1 fuel tank wouldn't hold much longer. If something wasn't done soon, it would collapse like an accordion.

Colonel Morris asked Mazzaro if he knew what Kennedy had just done. After hearing about it, Mazzaro became furious.

Morris called the command post on the radio and provided the latest tank pressure readings, without revealing how he'd obtained them. Then Mazzaro got on the radio and told Little Rock that Kennedy had disobeyed orders and violated the two-man rule.

Kennedy didn't care about any of this bullshit. He wanted to save the missile. And he had a plan, a good plan that would work.

Morris agreed to hear it.

We need to open the silo door, Kennedy said. That would release a lot of the fuel vapor, lower the heat in the silo, and relieve the pressure on the stage 1 oxidizer tank. Then we need to drop the work platformsâall nine levels of themâto support the missile and keep it upright. The platforms could prevent the missile from collapsing or falling against the silo wall. And then we need to send a PTS team down there to stabilize the stage 1 fuel tank, to fill it with nitrogen and restore the positive pressure.

For Kennedy's plan to work, somebody would have to reenter the control center so that the platforms could be lowered and the silo door opened. Al Childers and Rodney Holder said they were willing to do it, if there was any chance of saving the missile.

Colonel Morris listened carefully and then spoke to the command post.

About fifteen minutes later, Morris told Kennedy the command post's response: nothing, absolutely nothing, was to be done without approval from SAC headquarters in Omaha. Lieutenant General Lloyd R. Leavitt, Jr., the vice commander in chief of the Strategic Air Command, was now in charge of the launch complex in Damascus. The problem with the missile and ideas about how to resolve it were being discussed. It was 9:30

P.M.,

almost three hours since the socket had been dropped. Until new orders came from Omaha, Morris said, everyone would have to sit tight.

F

red Charles Iklé began his research on bomb destruction as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Born and raised in an alpine village near Saint Moritz, he'd spent the Second World War amid the safety of neutral Switzerland. In 1949, Iklé left his studies in Chicago and traveled through bombed-out Germany. The war hadn't touched his family directly, and he wanted to know how people coped with devastation on such a massive scale. One of the cities he visited, Hamburg, had suffered roughly the same number of casualties as Nagasakiâand had lost an even greater proportion of housing. A series of Allied bombing raids had

killed about 3.3 percent of Hamburg's population and

destroyed about half of its homes. Nevertheless, Iklé found, the people of Hamburg were resilient. They had not fled the city in panic. They'd tried to preserve the familiar routines of daily life and now seemed determined to rebuild houses, businesses, and stores at their original locations. “

A city re-adjusts to destruction somewhat as a living organism responds to injury,” Iklé later noted.

After returning to the United States, Iklé wrote a doctoral thesis that looked at the relationship between the intensity of aerial bombing and the density of a city's surviving population. The proponents of airpower, he suggested, had overestimated its lethal effects. Before the Second World War,

British planners had assumed that for every metric ton of high-explosive bombs dropped on a city, about seventy-two people would be killed or injured. The actual rate turned out to be only fifteen to twenty

casualties per ton. And the Royal Air Force strategy of targeting residential areas and “de-housing” civilians proved disappointing. The supply of urban housing was much more elastic than expected, as people who still had homes invited their homeless friends, neighbors, and family members to come and stay.

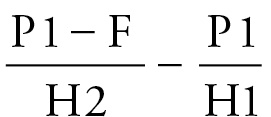

Iklé devised a simple formula to predict how crowded the houses of a bombed-out city might become. If P1 = the population of a city before destruction, P2 = the population of a city after destruction, H1 = the number of housing units before destruction, H2 = the number of housing units after destruction, and F = the number of fatalities, then “

the fully compensating increase in housing density,” could be expressed as a mathematical equation:

Iklé was impressed by the amount of urban hardship and overcrowding that people could endure. But there were limits. The tipping point seemed to be reached

when about 70 percent of a city's homes were destroyed. That's when people began to leave en masse and seek shelter in the countryside.

Iklé's dissertation attracted the attention of the RAND Corporation, and he was soon invited to join its social sciences division. Created in 1946 as a joint venture of the Army Air Forces and the Douglas Aircraft Company,

Project RAND became one of America's first think tanks, a university without students where scholars and Nobel laureates from a wide variety of disciplines could spend their days contemplating the future of airpower. The organization gained early support from General Curtis LeMay, whose training as a civil engineer had greatly influenced his military thinking. LeMay wanted the nation's best civilian minds to develop new weapons, tactics, and technologies for the Army Air Forces.

RAND's first study, “Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship,” outlined the military importance of satellites, more than a decade before one was launched. RAND subsequently conducted pioneering research on game theory, computer networking, artificial

intelligence, systems analysis, and nuclear strategy. Having severed its ties to Douglas Aircraft, RAND became a nonprofit corporation operating under an exclusive contract to the Air Force. At the RAND headquarters in Santa Monica, California, not far from the beach, amid a freewheeling intellectual atmosphere where no idea seemed too outlandish to explore, physicists, mathematicians, economists, sociologists, psychologists, computer scientists, and historians collaborated on top secret studies. Behind the whole enterprise lay a profound faith in the application of science and reason to warfare. The culture of the place was rigorously unsentimental. Analysts at RAND were encouraged to consider every possibility, calmly, rationally, and without emotionâto think about the unthinkable, in defense of the United States.

While immersed in a number of projects at RAND, Fred Iklé continued to study what happens when cities are bombed. His book on the subject,

The Social Impact of Bomb Destruction

,

appeared in 1958. It included his earlier work on the devastation of Hamburg and addressed the question of how urban populations would respond to nuclear attacks. Iklé warned that far more thought was being devoted to planning a nuclear war than to preparing for the aftermath of one. “

It is not a pleasant task to deal realistically with such potentially large-scale and gruesome destruction,” Iklé wrote in the preface. “But since we live in the shadow of nuclear warfare, we must face its consequences intelligently and prepare to cope with them.”

Relying largely on statistics, excluding any moral or humanitarian considerations, and writing with cool, Swiss precision, Iklé suggested that the Second World War strategy of targeting civilians had failed to achieve its aims.

The casualties were disproportionately women, children, and the elderlyânot workers essential to the war effort. Cities adapted to the bombing, and their morale wasn't easily broken.

Even in Hiroshima, the desire to fight back survived the blast: when rumors spread that San Francisco, San Diego, and Los Angeles had been destroyed by Japanese atomic bombs, people became lighthearted and cheerful, hoping the war could still be won.

A nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union, however, would present a new set of dilemmas. The first atomic bomb to strike a city might not be the only one. Fleeing to the countryside and

remaining there might be the logical thing to do. Iklé conjured a nightmarish vision of ongoing nuclear attacks, millions of casualties, firestorms, “

the sheer terror of the enormous destruction,” friction between rural townspeople and urban refugees, victims of radiation sickness anxiously waiting days or weeks to learn if they'd received a fatal dose. It was naive to think that the only choice Americans now faced was “one worldâor none.” Nuclear weapons might never be abolished, and their use might not mean the end of mankind. Iklé wanted people to confront the threat of nuclear war with a sense of realism, not utopianism or apocalyptic despair. A nation willing to prepare for the worst might surviveâin some form or another.

Iklé had spent years contemplating the grim details of how America's cities could be destroyed. His interest in the subject was more than academic; he had a wife and two young daughters. If the war plans of the United States or the Soviet Union were deliberately set in motion, Iklé understood, as well as anyone, the horrors that would be unleashed. A new and unsettling concern entered his mind: What if a nuclear weapon was detonated by accident? What if one was used without the president's approvalâset off by a technical glitch, a saboteur, a rogue officer, or just a mistake? Could that actually happen? And could it inadvertently start a nuclear war? With RAND's support, Iklé began to investigate the risk of an accidental or unauthorized detonation. And what he learned was not reassuring.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

T

HE

THREAT

OF

ACCIDENTS

had increased during the past decade, as nuclear weapons became more numerous, more widely dispersedâand vastly more powerful. In the fall of 1949, American scientists had engaged in a fierce debate over whether to develop a hydrogen bomb, nicknamed “the Superbomb” or “the Super.” It promised to unleash a destructive force thousands of times greater than that of the bombs used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While those weapons derived their explosive power solely from nuclear fission (the splitting apart of heavy elements into lighter ones), the hydrogen bomb would draw upon an additional source of energy, thermonuclear fusion (the combination of light elements into heavier ones). Fission and fusion both released the neutrons essential for a chain reactionâbut

fusion released a lot more. The potential yield of an atomic bomb was limited by the amount of its fissile material. But the potential yield of a thermonuclear weapon seemed limitless; it might only need more hydrogen as fuel. The same energy that powered the sun and the stars could be harnessed to make cities disappear.

The physicist Edward Teller had devoted most of his time during the Manhattan Project to theoretical work on the Super. But the problem of how to ignite and sustain fusion reactions had never been solved. After the Soviet Union detonated an atomic bomb in August 1949, Teller began to lobby for a crash program to build a hydrogen bomb. He was tireless, stubborn, brilliant, and determined to get his way. “

It is my conviction that a peaceful settlement with Russia is possible only if we possess overwhelming superiority,” Teller argued. “If the Russians demonstrate a Super before we possess one, our situation will be hopeless.”

The General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission discussed Teller's proposal and voted unanimously to oppose it. Headed by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the committee said that the hydrogen bomb had no real military value and would encourage “

the policy of exterminating civilian populations.” Six of the committee members signed a statement warning that the bomb could become “

a weapon of genocide.” Two others, the physicists Enrico Fermi and Isidor Rabi, hoped that the Super could be banned through an international agreement, arguing that such a bomb would be “

a danger to humanity . . . an evil thing considered in any light.”

David Lilienthal, the head of the AEC, opposed developing a hydrogen bomb, as did a majority of the AEC's commissioners. But one of them, Lewis L. Strauss, soon emerged as an influential champion of the weapon. Strauss wasn't a physicist or a former Manhattan Project scientist. He was a retired Wall Street financier with a high school education, a passion for science, and a deep mistrust of the Soviet Union. At the AEC, he'd been largely responsible for the monitoring system that detected the Soviet atomic bomb test. Now he wanted the United States to make

a “quantum leap” past the Soviets, and

“proceed with all possible expedition to develop the thermonuclear weapon.”

Senator Brien McMahon, head of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, agreed with Strauss. A few years earlier, McMahon had been a critic of the atomic bomb and a leading opponent of military efforts to control it. But the political climate had changed: Democrats were under attack for being too “soft on Communism.” The Soviet Union now loomed as a dangerous, implacable enemyâand McMahon was facing reelection. If the Soviets developed a hydrogen bomb and the United States didn't, McMahon predicted that “

total power in the hands of total evil will equal destruction.” The Air Force backed the effort to build the Superbomb, as did the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project and the Joint Chiefs of Staffâalthough its chairman, General Omar Bradley, acknowledged that the weapon's greatest benefit was

most likely “psychological.”

On January 31, 1950, President Truman met with David Lilienthal, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson to discuss the Superbomb. Acheson and Johnson had already expressed their support for developing one. The president asked whether the Soviets could do it. His advisers suggested that they could. “

In that case, we have no choice,” Truman said. “We'll go ahead.”

Two weeks after the president's decision was publicly announced,

Albert Einstein read a prepared statement about the hydrogen bomb on national television. He criticized the militarization of American society, the intimidation of anyone who opposed it, the demands for loyalty and secrecy,

the “hysterical character” of the nuclear arms race, and

the “disastrous illusion” that this new weapon would somehow make America safer. “Every step appears as the unavoidable consequence of the preceding one,” Einstein said. “

In the end, there beckons more and more clearly general annihilation.”

Truman's decision to develop a hydrogen bomb had great symbolic importance. It sent a message to the Soviet leadershipâand to the American people. In a cold war without bloodshed or battlefields, the perception of strength mattered as much as the reality. A classified Pentagon report later stressed the central role that “

psychological considerations” played in nuclear deterrence. “

Weapons systems in themselves tell only part of the necessary story,” the report argued. The success of America's defense plans relied on an effective “

information program” aimed at the public:

What deters is not the capabilities and intentions we have, but the capabilities and intentions the enemy thinks we have. The central objective of a deterrent weapons system is, thus, psychological. The mission is persuasion.