Complete Works of Emile Zola (1873 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

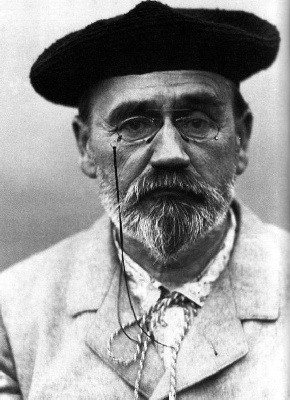

Authors: Émile Zola

While M. Zola thus expressed himself, we sat face to face, he in his favourite arm chair on one side of the fireplace, and I on the other, in the familiar room, with its three windows overlooking the lively road, while all around curvetted the scrolls and arabesques of the light fawn-tinted wall paper. And after chatting about Du Paty and Esterhazy we gradually lapsed into silence. It was a fateful hour. There were ninety-nine probabilities out of a hundred that the decision of the Cour de Cassation would be given that same afternoon; and whatever that decision might be we felt certain that before it was made public by any newspaper in London we should be apprised of it. We knew that five minutes after judgment should have been pronounced a telegram would be speeding through the wires to the Queen’s Hotel, Norwood.

M. Zola did not tell me his thoughts, yet I could guess them. We can generally guess the thoughts of those we love. But the hours went by and nothing came. How long they were, those judges! Whatever could be the cause of their delay? Surely — trained, practised men that they were, men who had spent their lives in seeking and proclaiming the truth — surely no element of doubt could have penetrated their minds at the final, the supreme moment.

Ah! the waiter entered, and there on his salver lay a buff envelope, within which must surely be the ardently awaited message that would tell us of victory or defeat. M. Zola could scarcely tear that envelope open; his hands trembled violently. And then came an anti-climax. The wire was from M. Fasquelle, who announced that he and his wife were inviting themselves to dinner at Norwood that evening.

It was welcome news, but not the news so impatiently expected. And, at last, suspense become intolerable, I resolved to go out and try to purchase some afternoon newspapers.

There had been rumours to the effect that as each individual judge might preface his decision by a declaration of the reasons which prompted it, the final judgment might after all be postponed until Monday. Both M. Zola and I had thought this improbable; still, there was a possibility of such delay, and perhaps it was on account of a postponement of the kind that the telegram we awaited had not arrived.

I scoured Upper Norwood for afternoon papers. There was, however, nothing to the point at that hour (about five P.M.) in ‘The Evening News,’ the ‘Globe,’ the ‘Echo,’ the ‘Star,’ the ‘Sun,’ the three ‘Gazettes.’ They, like we, were ‘waiting for the verdict.’ I went as far as the lower level station in the hope of finding some newspaper that might give an inkling of the position, and I found nothing at all. It was extremely warm, and I was somewhat excited. Thus I was perspiring terribly by the time I returned to the hotel, to learn that no telegram had come as yet, that things were still

in statu quo

.

Then all at once the waiter came up again with another buff envelope lying on his plated salver. And this time our anticipations were realised; here at last was the expected news. M. Zola read the telegram, then showed it to me.

It was brief, but sufficient. ‘Cheque postponed,’ it said; and Zola knew what those words meant. ‘Cheque paid’ would have signified that not only had revision been granted, but that all the proceedings against Dreyfus were quashed, and that he would not even have to be re-tried by another court-martial. And in a like way ‘cheque unpaid’ would have meant that revision had been refused by the Court. ‘Cheque postponed’ implied the granting of revision and a new court-martial.

The phraseology of this telegram, as of previous ones, had long since been arranged. For months many seemingly innocent ‘wires’ had been full of meaning. There had been no more enigmatical telegrams, as at the time of Henry’s arrest and death, but telegrams drafted in accordance with M. Zola’s instructions and each word of which was perfectly intelligible to him.

It often happened that the newspaper correspondents ‘were not in it.’ Things were known to M. Zola and at times to myself hours — and even days — before there was any mention of them in print. The blundering anti-Dreyfusites have often if not invariably overlooked the fact that their adversaries number men of acumen, skill, and energy. Far from it being true that money has played any role in the affair, everything has virtually been achieved by brains and courage. In fact, from first to last, the Revisionist agitation, whilst proving that the Truth must always ultimately conquer, has likewise shown the supremacy of true intellect over every other force in the world, whether wealth, or influence, or fanaticism.

But I must return to M. Zola. He now knew all he wished to know. As there had been no postponement of the Court’s decision there need be none of his return. A telegram to Paris announcing his departure from London was hastily drafted and I hurried with it to the post-office, meeting on my way M. and Mme. Fasquelle, who were walking towards the Queen’s Hotel.

We had a right merry little dinner that evening. We were all in the best of humours. M. Zola’s face was radiant. A great victory had been won; and then, too, he was going home!

He recalled the more amusing incidents of his exile; it seemed to him, said he, as if for months and months he had been living in a dream.

And M. Fasquelle broke in with a reminder that M. Zola must be very careful when he reached his house, and must in no wise damage the historic table for which he, Fasquelle, had given such a pile of money at the memorable auction in the Rue de Bruxelles.

Ah, that table! We were in a mood to laugh about anything, and we laughed at the thought of the table; at the thought, too, of all the simple-minded folk who had imagined that they would be able to purchase ‘souvenirs’ at the auction so abruptly brought to an end.

Then the Fasquelles, having been to the Oaks on the previous day, began to talk of Epsom, and the scene, unique in the whole world, which the famous racecourse presents during Derby week. M. Zola half regretted that he had missed going. ‘But I will go everywhere and see everything,’ he repeated, ‘the next time I come to England. I shall then be able to do so openly, without any playing at hide and seek. Oh, it won’t be till after the Paris Exhibition, that is certain, but I have written an oratorio for which Bruneau has composed the music, and if it is sung in London, as I hope, I shall come over and spend a month going about everywhere. But, of course,’ he added, with a twinkle in his eyes, ‘I have about two years’ imprisonment to do as things stand, so I must make no positive promises.’

The rest is soon told. Final arrangements were made, and we came away, M. and Mme. Fasquelle and myself, about ten o’clock. ‘It is your last night of exile,’ I said to M. Zola as I pressed his hand, ‘and it will soon be over. You must try to sleep well.’

‘Sleep!’ he replied. ‘Oh, there is no sleep for me to-night. From this moment I shall be counting the hours, the very minutes.’

‘It will make a change for you, Vizetelly,’ said M. Fasquelle, as he, Mme. Fasquelle, and myself walked towards the railway station. ‘You will be missing him now.’

This was true. All the routine, all the

alertes

, the meetings, the missions of those eleven months were about to cease abruptly. What had at first seemed to me novel had with time become confirmed habit, and for the first few days after M. Zola’s departure I felt my occupation gone.

That departure took place, as arranged, on Sunday evening, June 4. It was the day when President Loubet was cowardly assailed at a race-meeting by the friends and partisans of the foolish Duke of Orleans; but of all that we remained (

pro tem.

) in blissful ignorance. The Fasquelles went down to Norwood and brought M. Zola to Victoria. I was busy during the day preparing for the ‘Westminster Gazette’ an English epitome of the declaration which ‘L’Aurore’ was to publish on the morrow. That work accomplished, I met the others on their arrival in town. Wareham had been warned of the change in the programme on the previous night, and came up from Wimbledon with my wife. There was a hasty scramble of a dinner at a restaurant near Victoria. We were served, I remember, by a very amusing and familiar waiter, who, addressing M. Zola by preference (I wonder if he recognised him?), kept on repeating that he was a ‘citizen of the most noble Helvetian Confederation,’ and assured us that potatoes for two would be ample, and that chicken for three would be as much as we should care to eat. ‘Take this,’ said he, ‘it’s to-day’s. Don’t have that, it was cooked yesterday.’ And all this made us extremely merry. ‘It seems to me more than ever that I am living in a dream,’ said M. Zola after a final laugh. ‘That waiter has given the finishing touch to my illusion.’

The train started at nine P.M., and we had a full quarter of an hour at our disposal for our leave-takings in the dimly-lighted station. There were few passengers travelling that night, and few loiterers about. We made M. Zola take his seat in a compartment, and stood on guard before it talking to him. Only one gentleman, a short dapper individual with mutton-chop whiskers (Wareham suggested that he looked like a barrister), paid any attention to the master, and, it may be, recognised him. For the rest, all went well. There were

au revoirs

and handshakes all round, and messages, too, for one and another. And M. Zola would have his little joke. ‘If you should come across Esterhazy,’ he said to me, ‘tell him that I’ve gone back, and ask him when he’s coming.’

‘Well,’ I replied, ‘he will probably want another safe-conduct before answering that question.’

‘Do you think that a safe-conduct to take Dreyfus’s place would suit him?’ was M. Zola’s retort.

But the clock was now on the stroke of the hour, the carriage doors were hastily closed, and the signal for departure was given.

‘Au revoir, au revoir!’ A last handshake, and the train started. For another half-minute we could see our dear and illustrious friend at his carriage window waving his arm to us. And then he was gone. The responsibility which had so long rested on Wareham and myself was ended; Emile Zola’s exit was virtually over: shortly after five o’clock on the following morning he would once more be in Paris, ready to take his part in the final, crowning act of one of the greatest dramas that the world has ever witnessed. Truth was still marching on, and assuredly nothing would be able to stop it.

Resources

Zola, 1902 — one of the last photographs to be taken of the author

THE ROUGON-MACQUART FAMILY TREE

First Generation:

1. ADELAIDE FOUQUE, called AUNT DIDE, born in 1768, married in 1786 to Rougon, a placid, lubberly gardener; bears him a son in 1787; loses her husband in 1788; takes in 1789 a lover, Macquart, a smuggler, addicted to drink and half crazed; bears him a son in 1789, and a daughter in 1791; goes mad, and is sent to the Asylum of Les Tulettes in 1851; dies there of cerebral congestion in 1873 at 105 years of age. Supplies the original neurosis.

Second Generation:

2. PIERRE ROUGON, born in 1787, married in 1810 to Felicite Puech, an intelligent, active and healthy woman; has five children by her; dies in 1870, on the morrow of Sedan, from cerebral congestion due to overfeeding. An equilibrious blending of characteristics, the moral average of his father and mother, resembles them physically. An oil merchant, afterwards receiver of taxes.

3. ANTOINE MACQUART, born in 1789; a soldier in 1809; married in 1829 to a market dealer, Josephine Gavaudan, a vigorous, industrious, but intemperate woman; has three children by her; loses her in 1851; dies himself in 1873 from spontaneous combustion, brought about by alcoholism. A fusion of characteristics. Moral prepotency of and physical likeness to his father. A soldier, then a basket-maker, afterwards lives idle on his income.

4. URSULE MACQUART, born in 1791; married in 1810 to a journeyman-hatter, Mouret, a healthy man with a well-balanced mind. Bears him three children, dies of consumption in 1840. An adjunction of characteristics, her mother predominating morally and physically.

Third Generation:

5. EUGENE ROUGON, born in 1811, married in 1857 to Veronique Beulin d’Orcheres, by whom he has no children. A fusion of characteristics. Prepotency and ambition of his mother. Physical likeness to his father. A politician, at one time Cabinet Minister. Still alive in Paris, a deputy.