Complete Works of Emile Zola (631 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

“Rose! Rose!”

Gaga opened the door in astonishment and disappeared for a moment. When she returned:

“My dear,” she said, “it’s Fauchery. He’s out there at the end of the corridor. He won’t come any further, and he’s beside himself because you still stay near that body.”

Mignon had at last succeeded in urging the journalist upstairs. Lucy, who was still at the window, leaned out and caught sight of the gentlemen out on the pavement. They were looking up, making energetic signals to her. Mignon was shaking his fists in exasperation, and Steiner, Fontan, Bordenave and the rest were stretching out their arms with looks of anxious reproach, while Daguenet simply stood smoking a cigar with his hands behind his back, so as not to compromise himself.

“It’s true, dear,” said Lucy, leaving the window open; “I promised to make you come down. They’re all calling us now.”

Rose slowly and painfully left the chest.

“I’m coming down; I’m coming down,” she whispered. “It’s very certain she no longer needs me. They’re going to send in a Sister of Mercy.”

And she turned round, searching for her hat and shawl. Mechanically she filled a basin of water on the toilet table and while washing her hands and face continued:

“I don’t know! It’s been a great blow to me. We used scarcely to be nice to one another. Ah well! You see I’m quite silly over it now. Oh! I’ve got all sorts of strange ideas — I want to die myself — I feel the end of the world’s coming. Yes, I need air.”

The corpse was beginning to poison the atmosphere of the room. And after long heedlessness there ensued a panic.

“Let’s be off; let’s be off, my little pets!” Gaga kept saying. “It isn’t wholesome here.”

They went briskly out, casting a last glance at the bed as they passed it. But while Lucy, Blanche and Caroline still remained behind, Rose gave a final look round, for she wanted to leave the room in order. She drew a curtain across the window, and then it occurred to her that the lamp was not the proper thing and that a taper should take its place. So she lit one of the copper candelabra on the chimney piece and placed it on the night table beside the corpse. A brilliant light suddenly illumined the dead woman’s face. The women were horror-struck. They shuddered and escaped.

“Ah, she’s changed; she’s changed!” murmured Rose Mignon, who was the last to remain.

She went away; she shut the door. Nana was left alone with upturned face in the light cast by the candle. She was fruit of the charnel house, a heap of matter and blood, a shovelful of corrupted flesh thrown down on the pillow. The pustules had invaded the whole of the face, so that each touched its neighbor. Fading and sunken, they had assumed the grayish hue of mud; and on that formless pulp, where the features had ceased to be traceable, they already resembled some decaying damp from the grave. One eye, the left eye, had completely foundered among bubbling purulence, and the other, which remained half open, looked like a deep, black, ruinous hole. The nose was still suppurating. Quite a reddish crush was peeling from one of the cheeks and invading the mouth, which it distorted into a horrible grin. And over this loathsome and grotesque mask of death the hair, the beautiful hair, still blazed like sunlight and flowed downward in rippling gold. Venus was rotting. It seemed as though the poison she had assimilated in the gutters and on the carrion tolerated by the roadside, the leaven with which she had poisoned a whole people, had but now remounted to her face and turned it to corruption.

The room was empty. A great despairing breath came up from the boulevard and swelled the curtain.

“A BERLIN! A BERLIN! A BERLIN!”

PIPING HOT

Translated by Henry Vizetelly

Pot-Bouille

was serialised between January and April 1882 in the periodical

Le Gaulois,

before being published in book form by Charpentier the following year. The novel is an indictment of the manners and actions of the bourgeoisie of the Second French Empire. Set in a Parisian apartment building, the novel colourfully depicts the disparate and unpleasant lives of the inhabitants lurking behind the building’s new façade. Like

L’Assommoir

, the title is difficult to render in English, being a French slang term for a large cooking pot or cauldron used for preparing stews and casseroles. The title is intended to convey a sense of the contrasting ingredients, namely the various inhabitants of the building mixed together, forming a potent and heady mix like a strong stew. Zola’s aim was to illustrate the cupidity, ambition and depravity that lie beneath the dissimilating façade of a bourgeois apartment block.

The novel concerns the adventures of 22-year-old Octave Mouret, who moves into the building, taking a salesman’s job at a nearby shop. Though handsome and charming, Octave is rebuffed by Valérie Vabre and his employer’s wife Madame Hédouin, before commencing a passionless affair with Madame Pichon. His failure with Madame Hédouin prompts him to leave his employment, going instead to work for Auguste Vabre in the silk shop on the building’s ground floor. Octave Mouret will appear in Zola’s next novel as the grand department store owner in the celebrated study of commercial domination

Au Bonheur des Dames.

The first edition’s title page

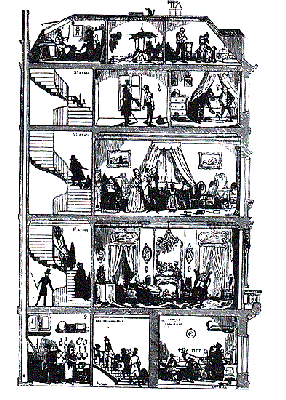

Illustration showing the layout of a building of this period

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XVIII

Poster of the film version of 1957

PREFACE

One day, in the middle of a long literary conversation, Théodore Duret said to me: “I have known in my life two men of supreme intelligence. I knew of both before the world knew of either. Never did I doubt, nor was it possible to doubt, but that they would one day or other gain the highest distinctions — those men were Léon Gambetta and Emile Zola.”

Of Zola I am able to speak, and I can thoroughly realise how interesting it must have been to have watched him, at that time, when he was poor and unknown, obtaining acceptance of his articles with difficulty, and surrounded by the feeble and trivial in spirit, who, out of inborn ignorance and acquired idiocy, look with ridicule on those who believe that there is still a new word to say, still a new cry to cry.

I did not know Emile Zola in those days, but he must have been then as he is now, and I should find it difficult to understand how any man of average discrimination could speak with him for half-an-hour without recognising that he was one of those mighty monumental intelligences, the statues of a century, that remain and are gazed upon through the long pages of the world’s history. This, at least, is the impression Emile Zola has always produced upon me. I have seen him in company, and company of no mean order, and when pitted against his compeers, the contrast has only made him appear grander, greater, nobler. The witty, the clever Alphonse Daudet, ever as ready for a supper party as a literary discussion, with all his splendid gifts, can do no more when Zola speaks than shelter himself behind an epigram; Edmond De Goncourt, aristocratic, dignified, seated amid his Japanese water-colours, bronzes, and Louis XV. furniture, bitterly admits, if not that there is a greater naturalistic god than he, at least that there is a colossus whose strength he is unable to oppose.

This is the position Emile Zola takes amid his contemporaries. By some strange power of assimilation, he appropriates and makes his own of all things; ideas that before were scattered, dislocated, are suddenly united, fitted into their places. In speaking, as in writing, he always appears greater than his subject, and, Titan-like, grasps it as a whole; in speaking, as in writing, the strength and beauty of his style is an unfailing use of the right word; each phrase is a solid piece of masonry, and as he talks an edifice of thought rises architecturally perfect and complete in design.

And it is of this side of Emile Zola’s genius that I wish particularly to speak — a side that has never been taken sufficiently into consideration, but which, nevertheless, is its ever-guiding and determinating quality. Emile Zola is to me a great epic poet, and he may be, I think, not inappropriately termed the Homer of modern life. For he, more than any other writer, it seems, possesses the power of seeing a subject as a whole, can divest it at will of all side issues, can seize with a firm, logical comprehension on the main lines of its construction, and that without losing sight of the remotest causes or the furthest consequences of its existence. It is here that his strength lies, and his is the strength which has conquered the world. Of his realism a great deal, of course, has been said, but only because it is the most obvious, not the most dominant quality of his work. The mistletoe invariably hides the oak from the eyes of the vulgar.

That Emile Zola has done well to characterise his creations with the vivid sentiment of modern life rather than the pale dream which reveals to us the past, that he was able to bend, to model, to make serviceable to his purpose the ephemeral habits and customs of our day, few will now deny. But this was only the off-shoot of his genius. That the colour of the nineteenth century with which he clothes the bodies of his heroes and heroines is not always exact, that none other has attempted to spin these garments before, I do not dispute. They will grow threadbare and fall to dust, even as the hide of the megatherium, of which only the colossal bones now remain to us wherewith to construct the fabric of the primeval world. ...

In the preceeding paragraph, I have said neither more nor less than my meaning, for I am convinced that the living history of no age has been as well written as the last half of the nineteenth century is in the Rougon-Macquart series. I pass over the question whether, in describing Renée’s dress, a mistake was made in the price of lace, also whether the author was wrong in permitting himself the anachronism of describing a fête in the opera-house a couple of years before the building was completed. Errors of this kind do not appear to me to be worth considering. What I maintain is, that what Emile Zola has done, and what he alone has done — and I do not make an exception even in the case of the mighty Balzac — is to have conceived and constructed the frame-work of a complex civilization like ours, in all its worse ramifications. Never, it seems to me, was the existence of the epic faculty more amply demonstrated than by the genealogical tree of this now celebrated family.