Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (1068 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

He paused, and looked again at his watch. Time proverbially works wonders. Time closed his lips.

Amelius replied with a heavy heart. The message from the Council had recalled him from the remembrance of Mellicent to the sense of his own position. “My experience of the world has been a very hard one,” he said. “I would gladly go back to Tadmor this very day, but for one consideration — ” He hesitated; the image of Sally was before him. The tears rose in his eyes; he said no more.

Brother Bawkwell, driven hard by time, got on his legs, and handed to Amelius the second of the two papers which he had taken out of his pocket-book.

“Here is a purely informal document,” he said; “being a few lines from Sister Mellicent, which I was charged to deliver to you. Be pleased to read it as quickly as you can, and tell me if there is any reply.”

There was not much to read: — ”The good people here, Amelius, have forgiven me and let me return to them. I am living happily now, dear, in my remembrances of you. I take the walks that we once took together — and sometimes I go out in the boat on the lake, and think of the time when I told you my sad story. Your poor little pet creatures are under my care; the dog, and the fawn, and the birds — all well, and waiting for you, with me. My belief that you will come back to me remains the same unshaken belief that it has been from the first. Once more I say it — you will find me the first to welcome you, when your spirits are sinking under the burden of life, and your heart turns again to the friends of your early days. Until that time comes, think of me now and then. Good-bye.”

“I am waiting,” said Brother Bawkwell, taking his hat in his hand.

Amelius answered with an effort. “Thank her kindly in my name,” he said: “that is all.” His head drooped while he spoke; he fell into thought as if he had been alone in the room.

But the emissary from Tadmor, warned by the minute-hand on the watch, recalled his attention to passing events. “You would do me a kindness,” said Brother Bawkwell, producing a list of names and addresses, “if you could put me in the way of finding the person named, eighth from the top. It’s getting on towards twenty minutes to three.”

The address thus pointed out was at no great distance, on the northern side of the Regent’s Park. Amelius, still silent and thoughtful, acted willingly as a guide. “Please thank the Council for their kindness to me,” he said, when they reached their destination. Brother Bawkwell looked at friend Amelius with a calm inquiring eye. “I think you’ll end in coming back to us,” he said. “I’ll take the opportunity, when I see you at Tadmor, of making a few needful remarks on the value of time.”

Amelius went back to the cottage, to see if Toff had returned, in his absence, before he paid his daily visit to Surgeon Pinfold. He called down the kitchen stairs, “Are you there, Toff?” And Toff answered briskly, “At your service, sir.”

The sky had become cloudy, and threatened rain. Not finding his umbrella in the hall, Amelius went into the library to look for it. As he closed the door behind him, Toff and his boy appeared on the kitchen stairs; both walking on tiptoe, and both evidently on the watch for something.

Amelius found his umbrella. But it was characteristic of the melancholy change in him that he dropped languidly into the nearest chair, instead of going out at once with the easy activity of happier days. Sally was in his mind again; he was rousing his resolution to set the doctor’s commands at defiance, and to insist on seeing her, come what might of it.

He suddenly looked up. A slight sound had startled him.

It was a faint rustling sound; and it came from the sadly silent room which had once been Sally’s.

He listened, and heard it again. He sprang to his feet — his heart beat wildly — he opened the door of the room.

She was there.

Her hands were clasped over her fast-heaving breast. She was powerless to look at him, powerless to speak to him — powerless to move towards him, until he opened his arms to her. Then, all the love and all the sorrow in the tender little heart flowed outward to him in a low murmuring cry. She hid her blushing face on his bosom. The rosy colour softly tinged her neck — the unspoken confession of all she feared, and all she hoped.

It was a time beyond words. They were silent in each other’s arms.

But under them, on the floor below, the stillness in the cottage was merrily broken by an outburst of dance-music — with a rhythmical thump-thump of feet, keeping time to the cheerful tune. Toff was playing his fiddle; and Toff’s boy was dancing to his father’s music.

After waiting a day or two for news from Amelius, and hearing nothing, Rufus went to make inquiries at the cottage.

“My master has gone out of town, sir,” said Toff, opening the door.

“Where?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Anybody with him?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Any news of Sally?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

Rufus stepped into the hall. “Look here, Mr. Frenchman, three times is enough. I have already apologized for treating you like a teetotum, on a former occasion. I’m afraid I shall do it again, sir, if I don’t get an answer to my next question — my hands are itching to be at you, they are! When is Amelius expected back?”

“Your question is positive, sir,” said Toff, with dignity. “I am happy to be able to meet it with a positive reply. My master is expected back in three weeks’ time.”

Having obtained some information at last, Rufus debated with himself what he should do next. He decided that “the boy was worth waiting for,” and that his wisest course (as a good American) would be to go back, and wait in Paris.

Passing through the Garden of the Tuileries, two or three days later, and crossing to the Rue de Rivoli, the name of one of the hotels in that quarter reminded him of Regina. He yielded to the prompting of curiosity, and inquired if Mr. Farnaby and his niece were still in Paris.

The manager of the hotel was in the porter’s lodge at the time. So far as he knew, he said, Mr. Farnaby and his niece, and an English gentleman with them, were now on their travels. They had left the hotel with an appearance of mystery. The courier had been discharged; and the coachman of the hired carriage which took them away had been told to drive straight forward until further orders. In short, as the manager put it, the departure resembled a flight. Remembering what his American agent had told him, Rufus received this information without surprise. Even the apparently incomprehensible devotion of Mr. Melton to the interests of such a man as Farnaby, failed to present itself to him as a perplexing circumstance. To his mind, Mr. Melton’s conduct was plainly attributable to a reward in prospect; and the name of that reward was — Miss Regina.

At the end of the three weeks, Rufus returned to London.

Once again, he and Toff confronted each other on the threshold of the door. This time, the genial old man presented an appearance that was little less than dazzling. From head to foot he was arrayed in new clothes; and he exhibited an immense rosette of white ribbon in his button-hole.

“Thunder!” cried Rufus. “Here’s Mr. Frenchman going to be married!”

Toff declined to humour the joke. He stood on his dignity as stiffly as ever. “Pardon me, sir, I possess a wife and family already.”

“Do you, now? Well — none of your know-nothing answers this time. Has Amelius come back?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And what’s the news of Sally?”

“Good news, sir. Miss Sally has come back too.”

“You call that good news, do you? I’ll say a word to Amelius. What are you standing there for? Let me by.”

“Pardon me once more, sir. My master and Miss Sally do not receive visitors today.”

“Your master and Miss Sally?” Rufus repeated. “Has this old creature been liquoring up a little too freely? What do you mean,” he burst out, with a sudden change of tone to stern surprise — ”what do you mean by putting your master and Sally together?”

Toff shot his bolt at last. “They will be together, sir, for the rest of their lives. They were married this morning.”

Rufus received the blow in dead silence. He turned about, and went back to his hotel.

Reaching his room, he opened the despatch box in which he kept his correspondence, and picked out the long letter containing the description by Amelius of his introduction to the ladies of the Farnaby family. He took up the pen, and wrote the indorsement which has been quoted as an integral part of the letter itself, in the Second Book of this narrative: —

“Ah, poor Amelius! He had better have gone back to Miss Mellicent, and put up with the little drawback of her age. What a bright lovable fellow he was! Goodbye to Goldenheart!”

Were the forebodings of Rufus destined to be fulfilled? This question will be answered, it is hoped, in a Second Series of The Fallen Leaves. The narrative of the married life of Amelius presents a subject too important to be treated within the limits of the present story — and the First Series necessarily finds its end in the culminating event of his life, thus far.

THE END

This sensation novel was published in 1880 and dedicated to Alberto Caccia, Collins’ Italian translator.

Based on the 1858 play,

The Red Vial

, Collins’ attempt to write for ‘the masses’ resulted in an unduly melodramatic tone.

The novel, however, is notable for the way it handles the treatment of lunatics and the mentally retarded; and for the creation of a female character who is effective both in business and as a philanthropist.

The plot revolves around the use of poisons and includes forensic details applicable to detective fiction.

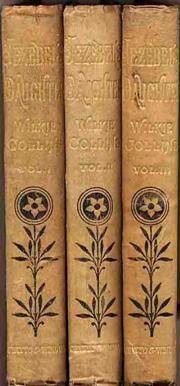

The first edition

JEZEBEL’S DAUGHTER