Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (1879 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

“Very likely; but I didn’t attend to it. When the day’s work is done, I take my walk. Then I have my supper, my drop of grog, and my pipe. Then I go to bed. A dull existence you think, I daresay! I had a miserable life, sir, when I was young. A bare subsistence, and a little rest, before the last perfect rest in the grave — that is all I want. The world has gone by me long ago. So much the better.”

The poor man spoke honestly. I was ashamed of having doubted him. I returned to the subject of the knife.

“Do you know where it was purchased, and by whom?” I asked.

“My memory is not so good as it was,” he said; “but I have got something by me that helps it.”

He took from a cupboard a dirty old scrapbook. Strips of paper, with writing on them, were pasted on the pages, as well as I could see. He turned to an index, or table of contents, and opened a page. Something like a flash of life showed itself on his dismal face.

“Ha! now I remember,” he said. “The knife was bought of my late brother-in-law, in the shop downstairs. It all comes back to me, sir. A person in a state of frenzy burst into this very room, and snatched the knife away from me, when I was only half way through the inscription!”

I felt that I was now close on discovery. “May I see what it is that has assisted your memory?” I asked.

“Oh yes. You must know, sir, I live by engraving inscriptions and addresses, and I paste in this book the manuscript instructions which I receive, with marks of my own on the margin. For one thing, they serve as a reference to new customers. And for another thing, they do certainly help my memory.”

He turned the book toward me, and pointed to a slip of paper which occupied the lower half of a page.

I read the complete inscription, intended for the knife that killed Zebedee, and written as follows:

“To John Zebedee. From Priscilla Thurlby.”

VII.

I DECLARE that it is impossible for me to describe what I felt when Priscilla’s name confronted me like a written confession of guilt. How long it was before I recovered myself in some degree, I cannot say. The only thing I can clearly call to mind is, that I frightened the poor engraver.

My first desire was to get possession of the manuscript inscription. I told him I was a policeman, and summoned him to assist me in the discovery of a crime. I even offered him money. He drew back from my hand. “You shall have it for nothing,” he said, “if you will only go away and never come here again.” He tried to cut it out of the page — but his trembling hands were helpless. I cut it out myself, and attempted to thank him. He wouldn’t hear me. “Go away!” he said, “I don’t like the look of you.”

It may be here objected that I ought not to have felt so sure as I did of the woman’s guilt, until I had got more evidence against her. The knife might have been stolen from her, supposing she was the person who had snatched it out of the engraver’s hands, and might have been afterward used by the thief to commit the murder. All very true. But I never had a moment’s doubt in my own mind, from the time when I read the damnable line in the engraver’s book.

I went back to the railway without any plan in my head. The train by which I had proposed to follow her had left Waterbank. The next train that arrived was for London. I took my place in it — still without any plan in my head.

At Charing Cross a friend met me. He said, “You’re looking miserably ill. Come and have a drink.”

I went with him. The liquor was what I really wanted; it strung me up, and cleared my head. He went his way, and I went mine. In a little while more, I determined what I would do.

In the first place, I decided to resign my situation in the police, from a motive which will presently appear. In the second place, I took a bed at a public-house. She would no doubt return to London, and she would go to my lodgings to find out why I had broken my appointment. To bring to justice the one woman whom I had dearly loved was too cruel a duty for a poor creature like me. I preferred leaving the police force. On the other hand, if she and I met before time had helped me to control myself, I had a horrid fear that I might turn murderer next, and kill her then and there. The wretch had not only all but misled me into marrying her, but also into charging the innocent housemaid with being concerned in the murder.

The same night I hit on a way of clearing up such doubts as still harassed my mind. I wrote to the rector of Roth, informing him that I was engaged to marry her, and asking if he would tell me (in consideration of my position) what her former relations might have been with the person named John Zebedee.

By return of post I got this reply:

SIR — Under the circumstances, I think I am bound to tell you confidentially what the friends and well-wishers of Priscilla have kept secret, for her sake.

“Zebedee was in service in this neighbourhood. I am sorry to say it, of a man who has come to such a miserable end — but his behavior to Priscilla proves him to have been a vicious and heartless wretch. They were engaged — and, I add with indignation, he tried to seduce her under a promise of marriage. Her virtue resisted him, and he pretended to be ashamed of himself. The banns were published in my church. On the next day Zebedee disappeared, and cruelly deserted her. He was a capable servant; and I believe he got another place. I leave you to imagine what the poor girl suffered under the outrage inflicted on her. Going to London, with my recommendation, she answered the first advertisement that she saw, and was unfortunate enough to begin her career in domestic service in the very lodging-house to which (as I gather from the newspaper report of the murder) the man Zebedee took the person whom he married, after deserting Priscilla. Be assured that you are about to unite yourself to an excellent girl, and accept my best wishes for your happiness.”

It was plain from this that neither the rector nor the parents and friends knew anything of the purchase of the knife. The one miserable man who knew the truth was the man who had asked her to be his wife.

I owed it to myself — at least so it seemed to me — not to let it be supposed that I, too, had meanly deserted her. Dreadful as the prospect was, I felt that I must see her once more, and for the last time.

She was at work when I went into her room. As I opened the door she started to her feet. Her cheeks reddened, and her eyes flashed with anger. I stepped forward — and she saw my face. My face silenced her.

I spoke in the fewest words I could find.

“I have been to the cutler’s shop at Waterbank,” I said. “There is the unfinished inscription on the knife, complete in your handwriting. I could hang you by a word. God forgive me — I can’t say the word.”

Her bright complexion turned to a dreadful clay-colour. Her eyes were fixed and staring, like the eyes of a person in a fit. She stood before me, still and silent. Without saying more, I dropped the inscription into the fire. Without saying more, I left her.

I never saw her again.

VIII.

BUT I heard from her a few days later. The letter has long since been burned. I wish I could have forgotten it as well. It sticks to my memory. If I die with my senses about me, Priscilla’s letter will be my last recollection on earth.

In substance it repeated what the rector had already told me. Further, it informed me that she had bought the knife as a keepsake for Zebedee, in place of a similar knife which he had lost. On the Saturday, she made the purchase, and left it to be engraved. On the Sunday, the banns were put up. On the Monday, she was deserted; and she snatched the knife from the table while the engraver was at work.

She only knew that Zebedee had added a new sting to the insult inflicted on her when he arrived at the lodgings with his wife. Her duties as cook kept her in the kitchen — and Zebedee never discovered that she was in the house. I still remember the last lines of her confession:

“The devil entered into me when I tried their door, on my way up to bed, and found it unlocked, and listened a while, and peeped in. I saw them by the dying light of the candle — one asleep on the bed, the other asleep by the fireside. I had the knife in my hand, and the thought came to me to do it, so that they might hang

her

for the murder. I couldn’t take the knife out again, when I had done it. Mind this! I did really like you — I didn’t say Yes, because you could hardly hang your own wife, if you found out who killed Zebedee.”

Since the past time I have never heard again of Priscilla Thurlby; I don’t know whether she is living or dead. Many people may think I deserve to be hanged myself for not having given her up to the gallows. They may, perhaps, be disappointed when they see this confession, and hear that I have died decently in my bed. I don’t blame them. I am a penitent sinner. I wish all merciful Christians good-by forever.

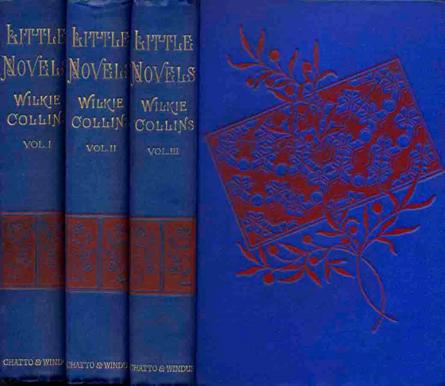

This collection of fourteen short stories was published in 1887.

All the stories had previously been issued with different titles in various American or English periodicals.

Unlike Collins’ earlier collections, there is no connecting narrative but most of the stories revolve around the theme of love and marriage, frequently across the social barriers of class and money.

Some also include supernatural or detective elements.

The first edition

LITTLE NOVELS

CONTENTS