Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2318 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

It is a tribute to the generally healthful and manly tone of the story of

Copperfield

that such should be the outcome of the eccentricities of this leading personage in it; and the superiority in this respect of Micawber over Skimpole is one of many indications of the inferiority of

Bleak House

to its predecessor. With leading resemblances that make it difficult to say which character best represents the principle or no principle of impecuniosity, there cannot be any doubt which has the advantage in moral and intellectual development. It is genuine humour against personal satire. Between the worldly circumstances of the two, there is nothing to choose; but as to everything else it is the difference between shabbiness and greatness. Skimpole’s sunny talk might be expected to please as much as Micawber’s gorgeous speech, the design of both being to take the edge off poverty. But in the one we have no relief from attendant meanness or distress, and we drop down from the airiest fancies into sordidness and pain; whereas in the other nothing pitiful or merely selfish ever touches us. At its lowest depth of what is worst, we never doubt that something better must turn up; and of a man who sells his bedstead that he may entertain his friend, we altogether refuse to think nothing but badly. This is throughout the free and cheery style of

Copperfield

. The masterpieces of Dickens’s humour are not in it; but he has nowhere given such variety of play to his invention, and the book is unapproached among his writings for its completeness of effect and uniform pleasantness of tone.

What has to be said hereafter of those writings generally, will properly restrict what is said here, as in previous instances, mainly to personal illustration. The

Copperfield

disclosures formerly made will for ever connect the book with the author’s individual story; but too much has been assumed, from those revelations, of a full identity of Dickens with his hero, and of a supposed intention that his own character as well as parts of his career should be expressed in the narrative. It is right to warn the reader as to this. He can judge for himself how far the childish experiences are likely to have given the turn to Dickens’s genius; whether their bitterness had so burnt into his nature, as, in the hatred of oppression, the revolt against abuse of power, and the war with injustice under every form displayed in his earliest books, to have reproduced itself only; and to what extent mere compassion for his own childhood may account for the strange fascination always exerted over him by child-suffering and sorrow. But, many as are the resemblances in Copperfield’s adventures to portions of those of Dickens, and often as reflections occur to David which no one intimate with Dickens could fail to recognise as but the reproduction of his, it would be the greatest mistake to imagine anything like a complete identity of the fictitious novelist with the real one, beyond the Hungerford scenes; or to suppose that the youth, who then received his first harsh schooling in life, came out of it as little harmed or hardened as David did. The language of the fiction reflects only faintly the narrative of the actual fact; and the man whose character it helped to form was expressed not less faintly in the impulsive impressionable youth, incapable of resisting the leading of others, and only disciplined into self-control by the later griefs of his entrance into manhood. Here was but another proof how thoroughly Dickens understood his calling, and that to weave fact with fiction unskilfully would be only to make truth less true.

The character of the hero of the novel finds indeed his right place in the story he is supposed to tell, rather by unlikeness than by likeness to Dickens, even where intentional resemblance might seem to be prominent. Take autobiography as a design to show that any man’s life may be as a mirror of existence to all men, and the individual career becomes altogether secondary to the variety of experiences received and rendered back in it. This particular form in imaginative literature has too often led to the indulgence of mental analysis, metaphysics, and sentiment, all in excess: but Dickens was carried safely over these allurements by a healthy judgment and sleepless creative fancy; and even the method of his narrative is more simple here than it generally is in his books. His imaginative growths have less luxuriance of underwood, and the crowds of external images always rising so vividly before him are more within control.

Consider Copperfield thus in his proper place in the story, and sequence as well as connection will be given to the varieties of its childish adventure. The first warm nest of love in which his vain fond mother, and her quaint kind servant, cherish him; the quick-following contrast of hard dependence and servile treatment; the escape from that premature and dwarfed maturity by natural relapse into a more perfect childhood; the then leisurely growth of emotions and faculties into manhood; these are component parts of a character consistently drawn. The sum of its achievement is to be a successful cultivation of letters; and often as such imaginary discipline has been the theme of fiction, there are not many happier conceptions of it. The ideal and real parts of the boy’s nature receive development in the proportions which contribute best to the end desired; the readiness for impulsive attachments that had put him into the leading of others, has underneath it a base of truthfulness on which at last he rests in safety; the practical man is the outcome of the fanciful youth; and a more than equivalent for the graces of his visionary days, is found in the active sympathies that life has opened to him. Many experiences have come within its range, and his heart has had room for all. Our interest in him cannot but be increased by knowing how much he expresses of what the author had himself gone through; but David includes far less than this, and infinitely more.

That the incidents arise easily, and to the very end connect themselves naturally and unobtrusively with the characters of which they are a part, is to be said perhaps more truly of this than of any other of Dickens’s novels. There is a profusion of distinct and distinguishable people, and a prodigal wealth of detail; but unity of drift or purpose is apparent always, and the tone is uniformly right. By the course of the events we learn the value of self-denial and patience, quiet endurance of unavoidable ills, strenuous effort against ills remediable; and everything in the fortunes of the actors warns us, to strengthen our generous emotions and to guard the purities of home. It is easy thus to account for the supreme popularity of

Copperfield

, without the addition that it can hardly have had a reader, man or lad, who did not discover that he was something of a Copperfield himself. Childhood and youth live again for all of us in its marvellous boy-experiences. Mr. Micawber’s presence must not prevent my saying that it does not take the lead of the other novels in humorous creation; but in the use of humour to bring out prominently the ludicrous in any object or incident without excluding or weakening its most enchanting sentiment, it stands decidedly first. It is the perfection of English mirth. We are apt to resent the exhibition of too much goodness, but it is here so qualified by oddity as to become not merely palatable but attractive; and even pathos is heightened by what in other hands would only make it comical. That there are also faults in the book is certain, but none that are incompatible with the most masterly qualities; and a book becomes everlasting by the fact, not that faults are not in it, but that genius nevertheless is there.

Of its method, and its author’s generally, in the delineation of character, something will have to be said on a later page. The author’s own favourite people in it, I think, were the Peggotty group; and perhaps he was not far wrong. It has been their fate, as with all the leading figures of his invention, to pass their names into the language, and become types; and he has nowhere given happier embodiment to that purity of homely goodness, which, by the kindly and all-reconciling influences of humour, may exalt into comeliness and even grandeur the clumsiest forms of humanity. What has been indicated in the style of the book as its greatest charm is here felt most strongly. The ludicrous so helps the pathos, and the humour so uplifts and refines the sentiment, that mere rude affection and simple manliness in these Yarmouth boatmen, passed through the fires of unmerited suffering and heroic endurance, take forms half-chivalrous half-sublime. It is one of the cants of critical superiority to make supercilious mention of the serious passages in this great writer; but the storm and shipwreck at the close of

Copperfield

, when the body of the seducer is flung dead upon the shore amid the ruins of the home he has wasted and by the side of the man whose heart he has broken, the one as unconscious of what he had failed to reach as the other of what he has perished to save, is a description that may compare with the most impressive in the language. There are other people drawn into this catastrophe who are among the failures of natural delineation in the book. But though Miss Dartle is curiously unpleasant, there are some natural traits in her (which Dickens’s least life-like people are never without); and it was from one of his lady friends, very familiar to him indeed, he copied her peculiarity of never saying anything outright, but hinting it merely, and making more of it that way. Of Mrs. Steerforth it may also be worth remembering that Thackeray had something of a fondness for her. “I knew how it would be when I began,” says a pleasant letter all about himself written immediately after she appeared in the story. “My letters to my mother are like this, but then she likes ‘em — like Mrs. Steerforth: don’t you like Mrs. Steerforth?”

Turning to another group there is another elderly lady to be liked without a shadow of misgiving; abrupt, angular, extravagant, but the very soul of magnanimity and rectitude; a character thoroughly made out in all its parts; a gnarled and knotted piece of female timber, sound to the core; a woman Captain Shandy would have loved for her startling oddities, and who is linked to the gentlest of her sex by perfect womanhood. Dickens has done nothing better, for solidness and truth all round, than Betsey Trotwood. It is one of her oddities to have a fool for a companion; but this is one of them that has also most pertinence and wisdom. By a line thrown out in

Wilhelm Meister

, that the true way of treating the insane was, in all respects possible, to act to them as if they were sane, Goethe anticipated what it took a century to apply to the most terrible disorder of humanity; and what Mrs. Trotwood does for Mr. Dick goes a step farther, by showing how often asylums might be dispensed with, and how large might be the number of deficient intellects manageable with patience in their own homes. Characters hardly less distinguishable for truth as well as oddity are the kind old nurse and her husband the carrier, whose vicissitudes alike of love and of mortality are condensed into the three words since become part of universal speech,

Barkis is willin’

. There is wholesome satire of much utility in the conversion of the brutal schoolmaster of the earlier scenes into the tender Middlesex magistrate at the close. Nor is the humour anywhere more subtle than in the country undertaker, who makes up in fullness of heart for scantness of breath, and has so little of the vampire propensity of the town undertaker in

Chuzzlewit

, that he dares not even inquire after friends who are ill for fear of unkindly misconstruction. The test of a master in creative fiction, according to Hazlitt, is less in contrasting characters that are unlike than in distinguishing those that are like; and to many examples of the art in Dickens, such as the Shepherd and Chadband, Creakle and Squeers, Charley Bates and the Dodger, the Guppys and the Wemmicks, Mr. Jaggers and Mr. Vholes, Sampson Brass and Conversation Kenge, Jack Bunsby, Captain Cuttle, and Bill Barley, the Perkers and Pells, the Dodsons and Fogs, Sarah Gamp and Betsy Prig, and a host of others, is to be added the nicety of distinction between those eminent furnishers of funerals, Mr. Mould and Messrs. Omer and Joram. All the mixed mirth and sadness of the story are skilfully drawn into the handling of this portion of it; and, amid wooings and preparations for weddings and church-ringing bells for baptisms, the steadily-going rat-tat of the hammer on the coffin is heard.

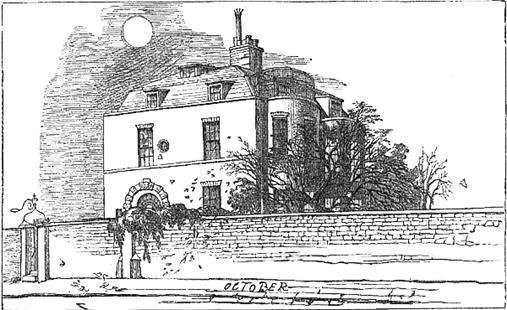

Of the heroines who divide so equally between them the impulsive, easily swayed, not disloyal but sorely distracted affections of the hero, the spoilt foolishness and tenderness of the loving little child-wife, Dora, is more attractive than the too unfailing wisdom and self-sacrificing goodness of the angel-wife, Agnes. The scenes of the courtship and housekeeping are matchless; and the glimpses of Doctors’ Commons, opening those views, by Mr. Spenlow, of man’s vanity of expectation and inconsistency of conduct in neglecting the sacred duty of making a will, on which he largely moralizes the day before he dies intestate, form a background highly appropriate to David’s domesticities. This was among the reproductions of personal experience in the book; but it was a sadder knowledge that came with the conviction some years later, that David’s contrasts in his earliest married life between his happiness enjoyed and his happiness once anticipated, the “vague unhappy loss or want of something” of which he so frequently complains, reflected also a personal experience which had not been supplied in fact so successfully as in fiction. (A closing word may perhaps be allowed, to connect with Devonshire-terrace the last book written there. On the page opposite is engraved a drawing by Maclise of the house where so many of Dickens’s masterpieces were composed, done on the first anniversary of the day when his daughter Kate was born.)

DEVONSHIRE TERRACE.

DEVONSHIRE TERRACE.