Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2335 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

THE CHÂLET.

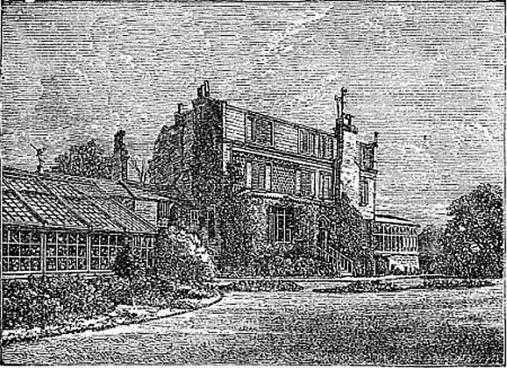

One or two more extracts from letters having reference to these changes may show something of the interest to him with which Gadshill thus grew under his hands. A sun-dial on his back-lawn had a bit of historic interest about it. “One of the balustrades of the destroyed old Rochester Bridge,” he wrote to his daughter in June 1859, “has been (very nicely) presented to me by the contractors for the works, and has been duly stone-masoned and set up on the lawn behind the house. I have ordered a sun-dial for the top of it, and it will be a very good object indeed.” “When you come down here next month,” he wrote to me, “we have an idea that we shall show you rather a neat house. What terrific adventures have been in action; how many overladen vans were knocked up at Gravesend, and had to be dragged out of Chalk-turnpike in the dead of the night by the whole equine power of this establishment; shall be revealed at another time.” That was in the autumn of 1860, when, on the sale of his London house, its contents were transferred to his country home. “I shall have an alteration or two to show you at Gadshill that greatly improve the little property; and when I get the workmen out this time, I think I’ll leave off.” October 1861 had now come, when the new bedrooms were built; but in the same month of 1863 he announced his transformation of the old coach-house. “I shall have a small new improvement to show you at Gads, which I think you will accept as the crowning ingenuity of the inimitable.” But of course it was not over yet. “My small work and planting,” he wrote in the spring of 1866, “really, truly, and positively the last, are nearly at an end in these regions, and the result will await summer inspection.” No, nor even yet. He afterwards obtained, by exchange of some land with the trustees of Watts’s Charity, the much coveted meadow at the back of the house of which heretofore he had the lease only; and he was then able to plant a number of young limes and chestnuts and other quick-growing trees. He had already planted a row of limes in front. He had no idea, he would say, of planting only for the benefit of posterity, but would put into the ground what he might himself enjoy the sight and shade of. He put them in two or three clumps in the meadow, and in a belt all round.

Still there were “more last words,” for the limit was only to be set by his last year of life. On abandoning his notion, after the American Readings, of exchanging Gadshill for London, a new staircase was put up from the hall; a parquet floor laid on the first landing; and a conservatory built, opening into both drawing-room and dining-room, “glass and iron,” as he described it, “brilliant but expensive, with foundations as of an ancient Roman work of horrible solidity.” This last addition had long been an object of desire with him; though he would hardly even now have given himself the indulgence but for the golden shower from America. He saw it first in a completed state on the Sunday before his death, when his younger daughter was on a visit to him. “Well, Katey,” he said to her, “now you see positively the last improvement at Gadshill;” and every one laughed at the joke against himself. The success of the new conservatory was unquestionable. It was the remark of all around him that he was certainly, from this last of his improvements, drawing more enjoyment than from any of its predecessors, when the scene for ever closed.

HOUSE AND CONSERVATORY: FROM THE MEADOW.

Of the course of his daily life in the country there is not much to be said. Perhaps there was never a man who changed places so much and habits so little. He was always methodical and regular; and passed his life from day to day, divided for the most part between working and walking, the same wherever he was. The only exception was when special or infrequent visitors were with him. When such friends as Longfellow and his daughters, or Charles Eliot Norton and his wife, came, or when Mr. Fields brought his wife and Professor Lowell’s daughter, or when he received other Americans to whom he owed special courtesy, he would compress into infinitely few days an enormous amount of sight seeing and country enjoyment, castles, cathedrals, and fortified lines, lunches and picnics among cherry orchards and hop-gardens, excursions to Canterbury or Maidstone and their beautiful neighbourhoods, Druid-stone and Blue Bell Hill. “All the neighbouring country that could be shown in so short a time,” he wrote of the Longfellow visit, “they saw. I turned out a couple of postilions in the old red jackets of the old red royal Dover road for our ride, and it was like a holiday ride in England fifty years ago.” For Lord Lytton he did the same, for the Emerson Tennents, for Mr. Layard and Mr. Helps, for Lady Molesworth and the Higginses (Jacob Omnium), and such other less frequent visitors.

Excepting on such particular occasions however, and not always even then, his mornings were reserved wholly to himself; and he would generally preface his morning work (such was his love of order in everything around him) by seeing that all was in its place in the several rooms, visiting also the dogs, stables, and kitchen garden, and closing, unless the weather was very bad indeed, with a turn or two round the meadow before settling to his desk. His dogs were a great enjoyment to him;

and, with his high road traversed as frequently as any in England by tramps and wayfarers of a singularly undesirable description, they were also a necessity. There were always two, of the mastiff kind, but latterly the number increased. His own favourite was Turk, a noble animal, full of affection and intelligence, whose death by a railway-accident, shortly after the Staplehurst catastrophe, caused him great grief. Turk’s sole companion up to that date was Linda, puppy of a great St. Bernard brought over by Mr. Albert Smith, and grown into a superbly beautiful creature. After Turk there was an interval of an Irish dog, Sultan, given by Mr. Percy Fitzgerald; a cross between a St. Bernard and a bloodhound, built and coloured like a lioness and of splendid proportions, but of such indomitably aggressive propensities, that, after breaking his kennel-chain and nearly devouring a luckless little sister of one of the servants, he had to be killed. Dickens always protested that Sultan was a Fenian, for that no dog, not a secretly sworn member of that body, would ever have made such a point, muzzled as he was, of rushing at and bearing down with fury anything in scarlet with the remotest resemblance to a British uniform. Sultan’s successor was Don, presented by Mr. Frederic Lehmann, a grand Newfoundland brought over very young, who with Linda became parent to a couple of Newfoundlands, that were still gambolling about their master, huge, though hardly out of puppydom, when they lost him. He had given to one of them the name of Bumble, from having observed, as he described it, “a peculiarly pompous and overbearing manner he had of appearing to mount guard over the yard when he was an absolute infant.” Bumble was often in scrapes. Describing to Mr. Fields a drought in the summer of 1868, when their poor supply of ponds and surface wells had become waterless, he wrote: “I do not let the great dogs swim in the canal, because the people have to drink of it. But when they get into the Medway, it is hard to get them out again. The other day Bumble (the son, Newfoundland dog) got into difficulties among some floating timber, and became frightened. Don (the father) was standing by me, shaking off the wet and looking on carelessly, when all of a sudden he perceived something amiss, and went in with a bound and brought Bumble out by the ear. The scientific way in which he towed him along was charming.” The description of his own reception, on his reappearance after America, by Bumble and his brother, by the big and beautiful Linda, and by his daughter Mary’s handsome little Pomeranian, may be added from his letters to the same correspondent. “The two Newfoundland dogs coming to meet me, with the usual carriage and the usual driver, and beholding me coming in my usual dress out at the usual door, it struck me that their recollection of my having been absent for any unusual time was at once cancelled. They behaved (they are both young dogs) exactly in their usual manner; coming behind the basket phaeton as we trotted along, and lifting their heads to have their ears pulled, a special attention which they receive from no one else. But when I drove into the stable-yard, Linda (the St. Bernard) was greatly excited; weeping profusely, and throwing herself on her back that she might caress my foot with her great fore-paws. Mary’s little dog too, Mrs. Bouncer, barked in the greatest agitation on being called down and asked by Mary, ‘Who is this?’ and tore round and round me like the dog in the Faust outlines.” The father and mother and their two sons, four formidable-looking companions, were with him generally in his later walks.

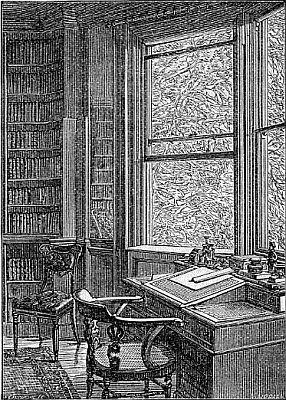

THE STUDY AT GADSHILL.

Round Cobham, skirting the park and village and passing the Leather Bottle famous in the page of

Pickwick

, was a favourite walk with Dickens. By Rochester and the Medway, to the Chatham Lines, was another. He would turn out of Rochester High-street through The Vines (where some old buildings, from one of which called Restoration-house he took Satis-house for

Great Expectations

, had a curious attraction for him), would pass round by Fort Pitt, and coming back by Frindsbury would bring himself by some cross fields again into the high road. Or, taking the other side, he would walk through the marshes to Gravesend, return by Chalk church, and stop always to have greeting with a comical old monk who for some incomprehensible reason sits carved in stone, cross-legged with a jovial pot, over the porch of that sacred edifice. To another drearier churchyard, itself forming part of the marshes beyond the Medway, he often took friends to show them the dozen small tombstones of various sizes adapted to the respective ages of a dozen small children of one family which he made part of his story of

Great Expectations

, though, with the reserves always necessary in copying nature not to overstep her modesty by copying too closely, he makes the number that appalled little Pip not more than half the reality. About the whole of this Cooling churchyard, indeed, and the neighbouring castle ruins, there was a weird strangeness that made it one of his attractive walks in the late year or winter, when from Higham he could get to it across country over the stubble fields; and, for a shorter summer walk, he was not less fond of going round the village of Shorne, and sitting on a hot afternoon in its pretty shaded churchyard. But on the whole, though Maidstone had also much that attracted him to its neighbourhood, the Cobham neighbourhood was certainly that which he had greatest pleasure in; and he would have taken oftener than he did the walk through Cobham park and woods, which was the last he enjoyed before life suddenly closed upon him, but that here he did not like his dogs to follow.

Don now has his home there with Lord Darnley, and Linda lies under one of the cedars at Gadshill.