Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (386 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

In those terms the letter ended. Miss Garth read it twice over. At the second reading the request which the lawyer now addressed to her, and the farewell words which had escaped Mr. Clare’s lips the day before, connected themselves vaguely in her mind. There was some other serious interest in suspense, known to Mr. Pendril and known to Mr. Clare, besides the first and foremost interest of Mrs. Vanstone’s recovery. Whom did it affect? The children? Were they threatened by some new calamity which their mother’s signature might avert? What did it mean? Did it mean that Mr. Vanstone had died without leaving a will?

In her distress and confusion of mind Miss Garth was incapable of reasoning with herself, as she might have reasoned at a happier time. She hastened to the antechamber of Mrs. Vanstone’s room; and, after explaining Mr. Pendril’s position toward the family, placed his letter in the hands of the medical men. They both answered, without hesitation, to the same purpose. Mrs. Vanstone’s condition rendered any such interview as the lawyer desired a total impossibility. If she rallied from her present prostration, Miss Garth should be at once informed of the improvement. In the meantime, the answer to Mr. Pendril might be conveyed in one word — Impossible.

“You see what importance Mr. Pendril attaches to the interview?” said Miss Garth.

Yes: both the doctors saw it.

“My mind is lost and confused, gentlemen, in this dreadful suspense. Can you either of you guess why the signature is wanted? or what the object of the interview may be? I have only seen Mr. Pendril when he has come here on former visits: I have no claim to justify me in questioning him. Will you look at the letter again? Do you think it implies that Mr. Vanstone has never made a will?”

“I think it can hardly imply that,” said one of the doctors. “But, even supposing Mr. Vanstone to have died intestate, the law takes due care of the interests of his widow and his children — ”

“Would it do so,” interposed the other medical man, “if the property happened to be in land?”

“I am not sure in that case. Do you happen to know, Miss Garth, whether Mr. Vanstone’s property was in money or in land?”

“In money,” replied Miss Garth. “I have heard him say so on more than one occasion.”

“Then I can relieve your mind by speaking from my own experience. The law, if he has died intestate, gives a third of his property to his widow, and divides the rest equally among his children.”

“But if Mrs. Vanstone — ”

“If Mrs. Vanstone should die,” pursued the doctor, completing the question which Miss Garth had not the heart to conclude for herself, “I believe I am right in telling you that the property would, as a matter of legal course, go to the children. Whatever necessity there may be for the interview which Mr. Pendril requests, I can see no reason for connecting it with the question of Mr. Vanstone’s presumed intestacy. But, by all means, put the question, for the satisfaction of your own mind, to Mr. Pendril himself.”

Miss Garth withdrew to take the course which the doctor advised. After communicating to Mr. Pendril the medical decision which, thus far, refused him the interview that he sought, she added a brief statement of the legal question she had put to the doctors; and hinted delicately at her natural anxiety to be informed of the motives which had led the lawyer to make his request. The answer she received was guarded in the extreme: it did not impress her with a favorable opinion of Mr. Pendril. He confirmed the doctors’ interpretation of the law in general terms only; expressed his intention of waiting at the cottage in the hope that a change for the better might yet enable Mrs. Vanstone to see him; and closed his letter without the slightest explanation of his motives, and without a word of reference to the question of the existence, or the non-existence, of Mr. Vanstone’s will.

The marked caution of the lawyer’s reply dwelt uneasily on Miss Garth’s mind, until the long-expected event of the day recalled all her thoughts to her one absorbing anxiety on Mrs. Vanstone’s account.

Early in the evening the physician from London arrived. He watched long by the bedside of the suffering woman; he remained longer still in consultation with his medical brethren; he went back again to the sick-room, before Miss Garth could prevail on him to communicate to her the opinion at which he had arrived.

When he called out into the antechamber for the second time, he silently took a chair by her side. She looked in his face; and the last faint hope died in her before he opened his lips.

“I must speak the hard truth,” he said, gently. “All that

can

be done

has

been done. The next four-and-twenty hours, at most, will end your suspense. If Nature makes no effort in that time — I grieve to say it — you must prepare yourself for the worst.”

Those words said all: they were prophetic of the end.

The night passed; and she lived through it. The next day came; and she lingered on till the clock pointed to five. At that hour the tidings of her husband’s death had dealt the mortal blow. When the hour came round again, the mercy of God let her go to him in the better world. Her daughters were kneeling at the bedside as her spirit passed away. She left them unconscious of their presence; mercifully and happily insensible to the pang of the last farewell.

Her child survived her till the evening was on the wane and the sunset was dim in the quiet western heaven. As the darkness came, the light of the frail little life — faint and feeble from the first — flickered and went out. All that was earthly of mother and child lay, that night, on the same bed. The Angel of Death had done his awful bidding; and the two Sisters were left alone in the world.

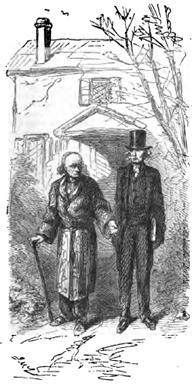

EARLIER than usual on the morning of Thursday, the twenty-third of July, Mr. Clare appeared at the door of his cottage, and stepped out into the little strip of garden attached to his residence.

After he had taken a few turns backward and forward, alone, he was joined by a spare, quiet, gray-haired man, whose personal appearance was totally devoid of marked character of any kind; whose inexpressive face and conventionally-quiet manner presented nothing that attracted approval and nothing that inspired dislike. This was Mr. Pendril — this was the man on whose lips hung the future of the orphans at Combe-Raven.

“The time is getting on,” he said, looking toward the shrubbery, as he joined Mr. Clare.

“My appointment with Miss Garth is for eleven o’clock: it only wants ten minutes of the hour.”

“Are you to see her alone?” asked Mr. Clare.

“I left Miss Garth to decide — after warning her, first of all, that the circumstances I am compelled to disclose are of a very serious nature.”

“And

has

she decided?”

“She writes me word that she mentioned my appointment, and repeated the warning I had given her to both the daughters. The elder of the two shrinks — and who can wonder at it? — from any discussion connected with the future which requires her presence so soon as the day after the funeral. The younger one appears to have expressed no opinion on the subject. As I understand it, she suffers herself to be passively guided by her sister’s example. My interview, therefore, will take place with Miss Garth alone — and it is a very great relief to me to know it.”

He spoke the last words with more emphasis and energy than seemed habitual to him. Mr. Clare stopped, and looked at his guest attentively.

“You are almost as old as I am, sir,” he said. “Has all your long experience as a lawyer not hardened you yet?”

“I never knew how little it had hardened me,” replied Mr. Pendril, quietly, “until I returned from London yesterday to attend the funeral. I was not warned that the daughters had resolved on following their parents to the grave. I think their presence made the closing scene of this dreadful calamity doubly painful, and doubly touching. You saw how the great concourse of people were moved by it — and

they

were in ignorance of the truth;

they

knew nothing of the cruel necessity which takes me to the house this morning. The sense of that necessity — and the sight of those poor girls at the time when I felt my hard duty toward them most painfully — shook me, as a man of my years and my way of life is not often shaken by any distress in the present or any suspense in the future. I have not recovered it this morning: I hardly feel sure of myself yet.”

“A man’s composure — when he is a man like you — comes with the necessity for it,” said Mr. Clare. “You must have had duties to perform as trying in their way as the duty that lies before you this morning.”

Mr. Pendril shook his head. “Many duties as serious; many stories more romantic. No duty so trying, no story so hopeless, as this.”

With those words they parted. Mr. Pendril left the garden for the shrubbery path which led to Combe-Raven. Mr. Clare returned to the cottage.

On reaching the passage, he looked through the open door of his little parlor and saw Frank sitting there in idle wretchedness, with his head resting wearily on his hand.

“I have had an answer from your employers in London,” said Mr. Clare. “In consideration of what has happened, they will allow the offer they made you to stand over for another month.”

Frank changed colour, and rose nervously from his chair.

“Are my prospects altered?” he asked. “Are Mr. Vanstone’s plans for me not to be carried out? He told Magdalen his will had provided for her. She repeated his words to me; she said I ought to know all that his goodness and generosity had done for both of us. How can his death make a change? Has anything happened?”

“Wait till Mr. Pendril comes back from Combe-Raven,” said his father. “Question him — don’t question me.”

The ready tears rose in Frank’s eyes.

“You won’t be hard on me?” he pleaded, faintly. “You won’t expect me to go back to London without seeing Magdalen first?”

Mr. Clare looked thoughtfully at his son, and considered a little before he replied.

“You may dry your eyes,” he said. “You shall see Magdalen before you go back.”

He left the room, after making that reply, and withdrew to his study. The books lay ready to his hand as usual. He opened one of them and set himself to read in the customary manner. But his attention wandered; and his eyes strayed away, from time to time, to the empty chair opposite — the chair in which his old friend and gossip had sat and wrangled with him good-humoredly for many and many a year past. After a struggle with himself he closed the book. “D — n the chair!” he said: “it

will

talk of him; and I must listen.” He reached down his pipe from the wall and mechanically filled it with tobacco. His hand shook, his eyes wandered back to the old place; and a heavy sigh came from him unwillingly. That empty chair was the only earthly argument for which he had no answer: his heart owned its defeat and moistened his eyes in spite of him. “He has got the better of me at last,” said the rugged old man. “There is one weak place left in me still — and

he

has found it.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Pendril entered the shrubbery, and followed the path which led to the lonely garden and the desolate house. He was met at the door by the man-servant, who was apparently waiting in expectation of his arrival.

“I have an appointment with Miss Garth. Is she ready to see me?”

“Quite ready, sir.”