Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (433 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

“I am sorry to hear it, sir. I felt hurt by Mr. Bygrave’s rude reception of me, but I was not aware that my judgment was prejudiced by it. Perhaps he received

you

, sir, with a warmer welcome?”

“He received me like a gentleman — that is all I think it necessary to say, Lecount — he received me like a gentleman.”

This answer satisfied Mrs. Lecount on the one doubtful point that had perplexed her. Whatever Mr. Bygrave’s sudden coolness toward herself might mean, his polite reception of her master implied that the risk of detection had not daunted him, and that the plot was still in full progress. The housekeeper’s eyes brightened; she had expressly calculated on this result. After a moment’s thinking, she addressed her master with another question: “You will probably visit Mr. Bygrave again, sir?”

“Of course I shall visit him — if I please.”

“And perhaps see Miss Bygrave, if she gets better?”

“Why not? I should be glad to know why not? Is it necessary to ask your leave first, Lecount?”

“By no means, sir. As you have often said (and as I have often agreed with you), you are master. It may surprise you to hear it, Mr. Noel, but I have a private reason for wishing that you should see Miss Bygrave again.”

Mr. Noel started a little, and looked at his housekeeper with some curiosity.

“I have a strange fancy of my own, sir, about that young lady,” proceeded Mrs. Lecount. “If you will excuse my fancy, and indulge it, you will do me a favor for which I shall be very grateful.”

“A fancy?” repeated her master, in growing surprise. “What fancy?”

“Only this, sir,” said Mrs. Lecount.

She took from one of the neat little pockets of her apron a morsel of note-paper, carefully folded into the smallest possible compass, and respectfully placed it in Noel Vanstone’s hands.

“If you are willing to oblige an old and faithful servant, Mr. Noel,” she said, in a very quiet and very impressive manner, “you will kindly put that morsel of paper into your waistcoat pocket; you will open and read it, for the first time,

when you are next in Miss Bygrave’s company

, and you will say nothing of what has now passed between us to any living creature, from this time to that. I promise to explain my strange request, sir, when you have done what I ask, and when your next interview with Miss Bygrave has come to an end.”

She courtesied with her best grace, and quietly left the room.

Noel Vanstone looked from the folded paper to the door, and from the door back to the folded paper, in unutterable astonishment. A mystery in his own house! under his own nose! What did it mean?

It meant that Mrs. Lecount had not wasted her time that morning. While the captain was casting the net over his visitor at North Shingles, the housekeeper was steadily mining the ground under his feet. The folded paper contained nothing less than a carefully written extract from the personal description of Magdalen in Miss Garth’s letter. With a daring ingenuity which even Captain Wragge might have envied, Mrs. Lecount had found her instrument for exposing the conspiracy in the unsuspecting person of the victim himself!

LATE that evening, when Magdalen and Mrs. Wragge came back from their walk in the dark, the captain stopped Magdalen on her way upstairs to inform her of the proceedings of the day. He added the expression of his opinion that the time had come for bringing Noel Vanstone, with the least possible delay, to the point of making a proposal. She merely answered that she understood him, and that she would do what was required of her. Captain Wragge requested her in that case to oblige him by joining a walking excursion in Mr. Noel Vanstone’s company at seven o’clock the next morning. “I will be ready,” she replied. “Is there anything more?” There was nothing more. Magdalen bade him good-night and returned to her own room.

She had shown the same disinclination to remain any longer than was necessary in the captain’s company throughout the three days of her seclusion in the house.

During all that time, instead of appearing to weary of Mrs. Wragge’s society, she had patiently, almost eagerly, associated herself with her companion’s one absorbing pursuit. She who had often chafed and fretted in past days under the monotony of her life in the freedom of Combe-Raven, now accepted without a murmur the monotony of her life at Mrs. Wragge’s work-table. She who had hated the sight of her needle and thread in old times — who had never yet worn an article of dress of her own making — now toiled as anxiously over the making of Mrs. Wragge’s gown, and bore as patiently with Mrs. Wragge’s blunders, as if the sole object of her existence had been the successful completion of that one dress. Anything was welcome to her — the trivial difficulties of fitting a gown: the small, ceaseless chatter of the poor half-witted creature who was so proud of her assistance, and so happy in her company — anything was welcome that shut her out from the coming future, from the destiny to which she stood self-condemned. That sorely-wounded nature was soothed by such a trifle now as the grasp of her companion’s rough and friendly hand — that desolate heart was cheered, when night parted them, by Mrs. Wragge’s kiss.

The captain’s isolated position in the house produced no depressing effect on the captain’s easy and equal spirits. Instead of resenting Magdalen’s systematic avoidance of his society, he looked to results, and highly approved of it. The more she neglected him for his wife the more directly useful she became in the character of Mrs. Wragge’s self-appointed guardian. He had more than once seriously contemplated revoking the concession which had been extorted from him, and removing his wife, at his own sole responsibility, out of harm’s way; and he had only abandoned the idea on discovering that Magdalen’s resolution to keep Mrs. Wragge in her own company was really serious. While the two were together, his main anxiety was set at rest. They kept their door locked by his own desire while he was out of the house, and, whatever Mrs. Wragge might do, Magdalen was to be trusted not to open it until he came back. That night Captain Wragge enjoyed his cigar with a mind at ease, and sipped his brandy-and-water in happy ignorance of the pitfall which Mrs. Lecount had prepared for him in the morning.

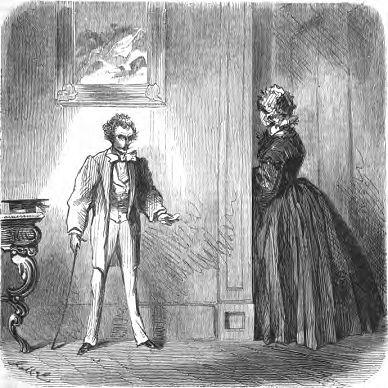

Punctually at seven o’clock Noel Vanstone made his appearance. The moment he entered the room Captain Wragge detected a change in his visitor’s look and manner. “Something wrong!” thought the captain. “We have not done with Mrs. Lecount yet.”

“How is Miss Bygrave this morning?” asked Noel Vanstone. “Well enough, I hope, for our early walk?” His half-closed eyes, weak and watery with the morning light and the morning air, looked about the room furtively, and he shifted his place in a restless manner from one chair to another, as he made those polite inquiries.

“My niece is better — she is dressing for the walk,” replied the captain, steadily observing his restless little friend while he spoke. “Mr. Vanstone!” he added, on a sudden, “I am a plain Englishman — excuse my blunt way of speaking my mind. You don’t meet me this morning as cordially as you met me yesterday. There is something unsettled in your face. I distrust that housekeeper of yours, sir! Has she been presuming on your forbearance? Has she been trying to poison your mind against me or my niece?”

If Noel Vanstone had obeyed Mrs. Lecount’s injunctions, and had kept her little morsel of note-paper folded in his pocket until the time came to use it, Captain Wragge’s designedly blunt appeal might not have found him unprepared with an answer. But curiosity had got the better of him; he had opened the note at night, and again in the morning; it had seriously perplexed and startled him; and it had left his mind far too disturbed to allow him the possession of his ordinary resources. He hesitated; and his answer, when he succeeded in making it, began with a prevarication.

Captain Wragge stopped him before he had got beyond his first sentence.

“Pardon me, sir,” said the captain, in his loftiest manner. “If you have secrets to keep, you have only to say so, and I have done. I intrude on no man’s secrets. At the same time, Mr. Vanstone, you must allow me to recall to your memory that I met you yesterday without any reserves on my side. I admitted you to my frankest and fullest confidence, sir — and, highly as I prize the advantages of your society, I can’t consent to cultivate your friendship on any other than equal terms.” He threw open his respectable frock-coat and surveyed his visitor with a manly and virtuous severity.

“I mean no offense!” cried Noel Vanstone, piteously. “Why do you interrupt me, Mr. Bygrave? Why don’t you let me explain? I mean no offense.”

“No offense is taken, sir,” said the captain. “You have a perfect right to the exercise of your own discretion. I am not offended — I only claim for myself the same privilege which I accord to you.” He rose with great dignity and rang the bell. “Tell Miss Bygrave,” he said to the servant, “that our walk this morning is put off until another opportunity, and that I won’t trouble her to come downstairs.”

This strong proceeding had the desired effect. Noel Vanstone vehemently pleaded for a moment’s private conversation before the message was delivered. Captain Wragge’s severity partially relaxed. He sent the servant downstairs again, and, resuming his chair, waited confidently for results. In calculating the facilities for practicing on his visitor’s weakness, he had one great superiority over Mrs. Lecount. His judgment was not warped by latent female jealousies, and he avoided the error into which the housekeeper had fallen, self-deluded — the error of underrating the impression on Noel Vanstone that Magdalen had produced. One of the forces in this world which no middle-aged woman is capable of estimating at its full value, when it acts against her, is the force of beauty in a woman younger than herself.

“You are so hasty, Mr. Bygrave — you won’t give me time — you won’t wait and hear what I have to say!” cried Noel Vanstone, piteously, when the servant had closed the parlor door.

“My family failing, sir — the blood of the Bygraves. Accept my excuses. We are alone, as you wished; pray proceed.”

Placed between the alternatives of losing Magdalen’s society or betraying Mrs. Lecount, unenlightened by any suspicion of the housekeeper’s ultimate object, cowed by the immovable scrutiny of Captain Wragge’s inquiring eye, Noel Vanstone was not long in making his choice. He confusedly described his singular interview of the previous evening with Mrs. Lecount, and, taking the folded paper from his pocket, placed it in the captain’s hand.

A suspicion of the truth dawned on Captain Wragge’s mind the moment he saw the mysterious note. He withdrew to the window before he opened it. The first lines that attracted his attention were these: “Oblige me, Mr. Noel, by comparing the young lady who is now in your company with the personal description which follows these lines, and which has been communicated to me by a friend. You shall know the name of the person described — which I have left a blank — as soon as the evidence of your own eyes has forced you to believe what you would refuse to credit on the unsupported testimony of Virginie Lecount.”

That was enough for the captain. Before he had read a word of the description itself, he knew what Mrs. Lecount had done, and felt, with a profound sense of humiliation, that his female enemy had taken him by surprise.

There was no time to think; the whole enterprise was threatened with irrevocable overthrow. The one resource in Captain Wragge’s present situation was to act instantly on the first impulse of his own audacity. Line by line he read on, and still the ready inventiveness which had never deserted him yet failed to answer the call made on it now. He came to the closing sentence — to the last words which mentioned the two little moles on Magdalen’s neck. At that crowning point of the description, an idea crossed his mind; his party-coloured eyes twinkled; his curly lips twisted up at the corners; Wragge was himself again. He wheeled round suddenly from the window, and looked Noel Vanstone straight in the face with a grimly-quiet suggestiveness of something serious to come.