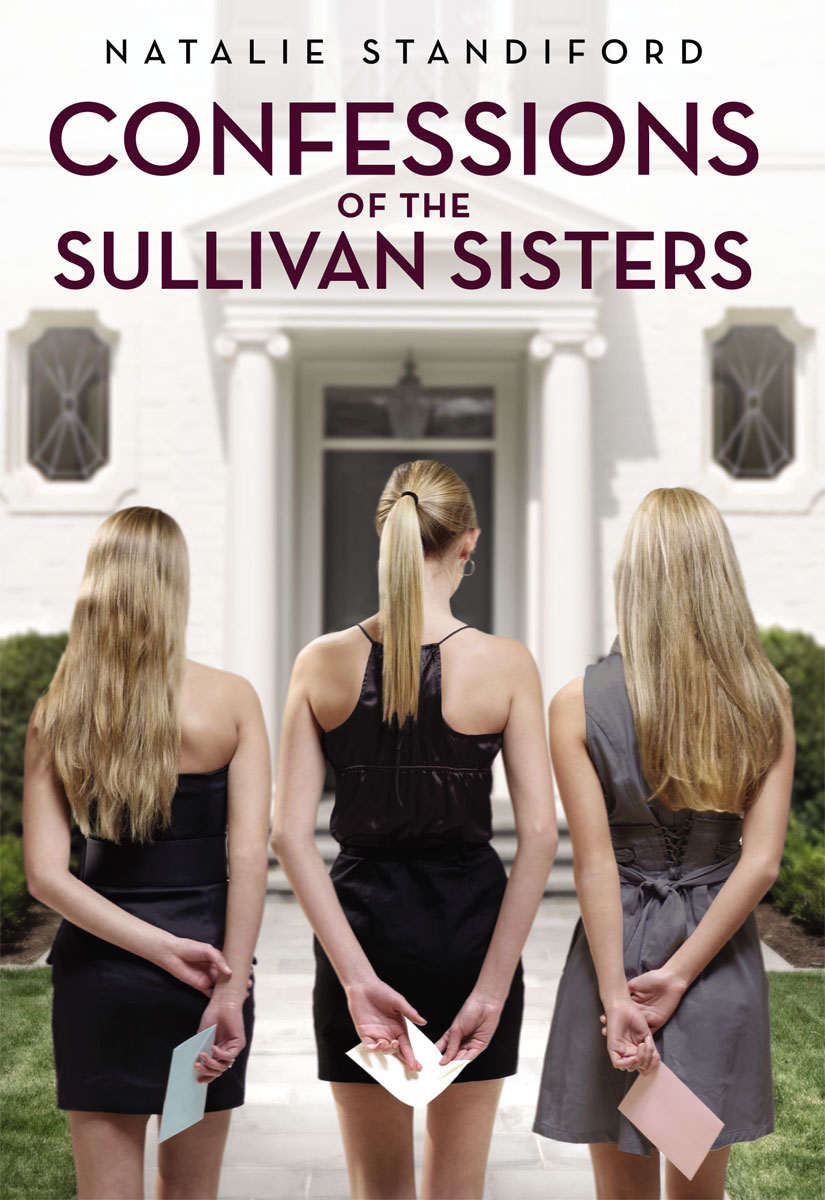

Confessions of the Sullivan Sisters

Read Confessions of the Sullivan Sisters Online

Authors: Natalie Standiford

NATALIE STANDIFORD

SCHOLASTIC PRESS •

NEW YORK

FOR

MY FAMILY:

MOM, DAD, KAKIE,

JOHN, JIM, AND

GREG

THE SULLIVAN FAMILY’S CHRISTMAS BEGAN IN THE

traditional way that year. All six children gathered at the top of the stairs in order, from youngest to oldest, and waited for the signal from Daddy-o that it was safe to come downstairs and inspect the work of Santa. Never mind that the oldest Sullivan child, St. John, was twenty-one. The youngest, Takey, was only six, and Daddy-o insisted on keeping up the annual rituals so Takey wouldn’t feel as if he’d missed everything.

The signal—“Joy to the World” sung by Nat King Cole—burst through the stereo speakers, and the six children—Takey, Sassy, Jane, Norrie, Sully, and St. John—trooped downstairs to the family room and rummaged under the tall Christmas tree for presents. Afterward they waded through the sea of discarded wrapping paper to the kitchen for a pancake breakfast cooked by Daddy-o. (Miss Maura had the day off, though she always stopped by with her husband, Dennis—known to the Sullivan children as Mr. Maura—to say hello and drop off presents around noon.) Ginger contributed her signature dish, sliced grapefruit halves sprinkled with Splenda. Slicing the grapefruit

was the most work she did in the kitchen all year, unless you counted transferring caviar from the tin to the silver serving dish on New Year’s Eve.

After breakfast, everyone retreated to their bedrooms to try on their new Christmas clothes and get ready for the big family dinner at Almighty’s. The Sullivans lived in a very big house, but Almighty—their grandmother Arden Louisa Norris Sullivan Weems Maguire Hightower Beckendorf, known to everyone in Baltimore as “Almighty Lou”—had a house that was a bona fide mansion, with a fancy name to match: Gilded Elms.

Christmas Eve at Gilded Elms was a party for family and friends. But Christmas Day dinner was a quieter occasion, usually just for Almighty and the Sullivans. That year, an unexpected guest joined the family at Almighty’s Christmas table: her lawyer, Mr. Calvin Murdoch. Mr. Murdoch had the silent, nodding, overly polite demeanor of an undertaker. Each of the Sullivans wondered what he was doing there while they quietly chewed on their turkey breast and passed around the homemade raisin bread.

In time, they got their answer.

After dinner, Almighty gathered her nearest and dearest in the library for a special announcement. She wore a simple black dress, which set off the bold white stripe in her iron-gray hair.

“I have recently learned that I may not have long to live,” she declared to gasps of surprise. “There is a tumor in my brain. If it doesn’t grow, I might live out my natural life as I was intended to, active and sentient. If, however, it grows—and the doctors say it has a distinct possibility of doing so—then I will quickly

decline. Therefore, I have revisited the affairs of my estate, financial and otherwise. In other words, I have changed my will.”

The family members gathered around her sat perfectly still, with a studied lack of emotion. No one wanted to appear upset at the possibility of a change in Almighty’s will. Such a change, however, would affect the fate of everyone in the room to a great degree. Almighty was very rich, and her son, his wife, and all of their children were completely dependent on the money she controlled.

“Alphonse,” Almighty continued, looking to Daddy-o, who’d been named after his late father, “I fear your entire family has been cut out of the will.”

The Sullivans gasped in horror. They couldn’t help themselves. This was just too awful.

“Now now, there is no need for alarm,” Almighty said, even if no other reaction seemed sensible.

“Mother, why?” Daddy-o asked.

“One of you has offended me deeply,” Almighty explained. “I’m not going to name names. But unless that person comes forward with a confession of his or her crime, submitted in writing to me by New Year’s Day, I will donate your share of my fortune to my favorite charity upon my death.”

“Which charity is that?” Ginger asked.

“Puppy Ponchos,” Almighty replied.

The Sullivans collectively restrained themselves from groaning. Puppy Ponchos provided rain ponchos for the dogs of people too poor to buy dog raincoats for themselves. In a city full of needy people and animals, it was the most useless charity

imaginable. No one in the Sullivan family understood why Puppy Ponchos was more deserving of Almighty’s money than they were. After all, hadn’t they put up with her for all these years? Didn’t that count for something?

“If the offending party submits the proper confession in time,” Almighty continued, “I will reinstate the family in my will. Or at least consider it.”

Almighty had spoken. And if Almighty wanted a confession, a confession she would get.

When the torturous dinner was finally over and the Sullivans had returned to their house, they gathered in the kitchen for a family meeting.

“Who could have offended Almighty so much?” St. John asked. “Which one of us could it be?”

“One of the girls,” Sully said.

“One of the girls,” Daddy-o repeated.

“Definitely one of the girls,” Ginger concurred.

Almighty had always been tough on the girls. And each of them had recently done something to upset their grandmother, no question about that.

And so it was agreed that the three girls—Norrie, Jane, and Sassy—would spend their Christmas break writing out a full confession of their crimes, to be handed to Almighty by midnight on New Year’s Eve.

After that, they would have to hope for the best.

Dear Almighty,

I confess.

You know what I did, and you know why—I did it for true love. Have you ever been in love, Almighty? You’ve been married five times—but have you been in love? You can’t resist it. You’re in its power. Helpless.

I tried to be good and dutiful and do what the family needed me to do. But I fell in love. Being in love made me crazy. That’s all I can say in my defense. I will tell you the whole story, from the beginning, and hope that will help you to understand, and to forgive me. (I hope I remember to take out all the curses. I’m trying to train myself not to curse anymore. But some people, like Sully and Jane, just don’t sound like themselves if they’re not cursing. So a few might have slipped in. If so, I’m sorry.)

I will return to my old dutiful self if it will save my family from poverty. I can do it. Dear Almighty, if you lift this curse from our heads I promise to be good for the rest of my life.

TO YOU, HE MUST HAVE SEEMED TO COME FROM NOWHERE.

But everybody comes from somewhere. And it’s not always Baltimore.

We met in September in a night class at Hopkins: Speed Reading. I wanted to learn how to read faster. That night I sat in the second-to-last row. I still had on my uniform from school—the navy blue cotton jumper with

SMPS

stitched over the breast in white thread.

I did my calculus homework while I waited for the class to start. The room filled up and the teacher came in and started talking about speed reading, but I wasn’t finished with my calculus homework, so I kept doing it while she talked. Not much of what she said was getting through to me—I’d been having concentration problems lately; that was partly why I wanted to learn how to speed read. But that wasn’t the only reason I was distracted. I also felt this heat coming from behind me, as if someone were watching me. I half turned to the left and saw an old man with a mustache, who wasn’t paying any attention to me at all. I half turned to the right and saw a tuft of frizzy black hair. That

was all I could see without turning all the way around, which seemed rude.

Through the whole class, the heat distracted me. Finally the teacher told us to take a ten-minute break. I stood up and turned around casually, very cool. This guy was sitting there, the guy with the frizzy black halo of hair, and he beamed up at me in such a warm way that it was no wonder I felt heat. He had a pale brown, creamy-skinned face with alert brown eyes and a short, wide nose that for some reason reminded me of a frog. A very cute little frog, topped with that hair.

“Hi,” he said. “I noticed you’re doing calculus homework.”

“Yes,” I said. “I guess I shouldn’t do that if I want to learn to speed read.”

“I think it’s really cute,” he said. “That you’re doing calculus homework.”

“It isn’t cute at all,” I told him. “There’s nothing cute about calculus.”

I wondered how old he was, then I wondered briefly if he realized I was still in high school. I say briefly because it only took me a second to realize that, duh, I was still wearing my uniform. Also, the homework was a dead giveaway. Sometimes I’m such an idiot.

“I think I’ll get some water,” I said. I wandered out into the hall and found a water fountain. I stared at it for a few seconds, as if I couldn’t remember how a water fountain worked. Something was fogging up my brain circuits. I was really beginning to worry about myself.

I finally remembered how to use the fountain and drank some water. Then I went back into the classroom and sat down. The guy in the seat behind mine nodded at me. I really liked his hair. It looked like what licorice cotton candy would look like, if they made licorice cotton candy.

The teacher started talking again, passing out an article for us to test our current reading speeds. My current speed turned out to be a hundred and fifty words a minute, which is pretty slow for a supposedly smart person.

I felt a tap on my shoulder. “What score did you get?” the cute guy behind me whispered.

I didn’t want to tell him, because my score was so low I was afraid he’d think I was mentally challenged. But I told him anyway. My first instinct is usually to be honest, which is a terrible weakness if you think about it.

“What’s your score?” I asked him.

“Four hundred words a minute,” he said.

I cursed—to myself—because Licorice Halo’s score was so much higher than mine, plus he had to be older, at least in college, and I hated to start out at a disadvantage that way.

And then I realized what I was thinking, and wondered,

Start out what?

Why did I care what this total stranger thought of my intelligence?

But I did, and that’s when I knew I was doomed.

When class was over, he looked at me as if he wanted to say something but was thinking the better of it, so instead of saying something, he just nodded and left. I figured it was the

uniform that turned him off. Some people find Catholic school uniforms scary. I cursed myself again for being too lazy to change before class—an adult night school class, what was I thinking?—and vowed to wear civvies the next week. I also vowed to find out his name so I wouldn’t have to think of him only in terms of his hair.

When I got home that night, Jane was in my room, smoking out the window. That drives me crazy. Next year when I go away to college it’ll be her turn to have the Tower Room and she can smoke her lungs out if she wants. But no matter how many times I yell at her she won’t stop, so I’ve kind of given up.

A police helicopter was circling the neighborhood, and Jane was watching its searchlight. “Can you see anything?” I asked. Sometimes, when the police copters come, you can catch sight of someone running down the street in the glare of the searchlight. But it’s hard to see much from up in the Tower Room in summer, when the leaves are so full it feels like a tree house. In winter, when the trees are bare, you can see the neighbors’ houses and the lights downtown.

Jane turned away from the window and blew a stream of smoke at me. “You look different.”

“Different how?” I asked.

She shrugged and took another puff. “I don’t know. Just different.”

“I am different,” I said. “I don’t think I’ll ever be the old Norrie again.”

She didn’t react much to that, since we Sullivans are all very dramatic, as you well know, Almighty. You’re the Drama Queen.

It’s hard to top the striptease Jane did in the middle of the school musical last year, or that time St. John announced that he was leaving for Paris in the morning to live there forever. Did you know about that? Daddy-o was afraid to tell you his twelve-year-old son had run off to Paris alone, because you’re always criticizing him for being too lax with us. It all blew over in a week. A friend of Daddy-o’s met St. John at the airport, and after a week of cafés and museums he flew home and declared that Paris was lovely but overrated.

So my announcement that I suddenly felt “different” didn’t have much impact. Jane said, “I didn’t know speed reading could change a person so much. And so speedily! Will the new Norrie trade rooms with me so I can smoke whenever I want?”

“No,” I said. “There will never be an incarnation of Norrie who will give up the Tower Room before she leaves for college. And you shouldn’t smoke anyway.”

“I know I shouldn’t.” She blew a stream of smoke out the window.

I didn’t tell Jane anything about the guy I’d met in Speed Reading class that night, because it was too early. I wanted to give the thing, whatever it turned out to be, a chance to happen first. Besides, if I told anyone, that would make it real, and I wasn’t ready for it to be real yet. I knew that

real

meant trouble.