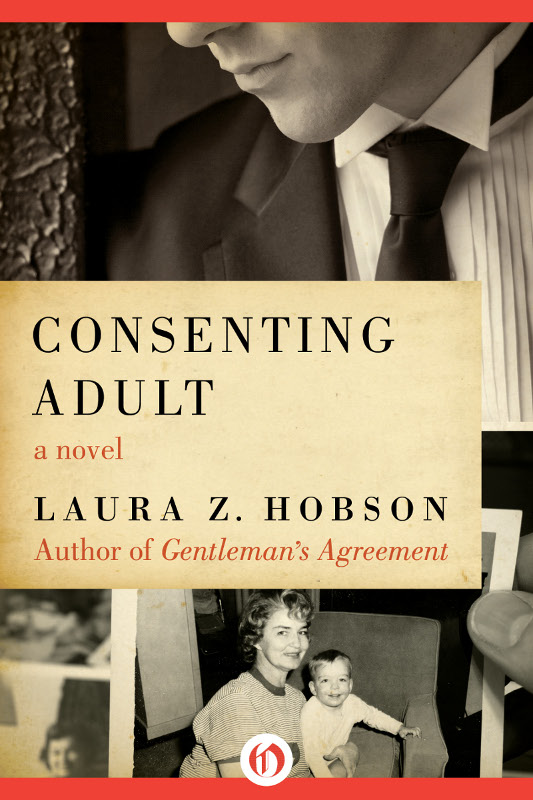

Consenting Adult

Authors: Laura Z. Hobson

Laura Z. Hobson

Contents

ContentsPart One

1960-1961

CHAPTER ONE

DEAR MAMA,

I’m sorry about all the rows during vacation, and I have something to tell you that I guess I better not put off any longer. You said that if I needed real psychoanalytic help, not just the visits with Mrs. Culkin, I could have it. Well now, I think I’m going to ask if you can manage it for me.

You see, I am a homosexual. I have fought it off for months and maybe years, but it just grows truer. I have never yet had an actual affair with anybody, I give you my word on that, not even Pete, whom I suppose you’ll think of right away because we room together and go places together. It’s just that I know it, more and more clearly all the time, and I finally thought I really ought to ask for help.

I know how much pain this will cause you, and shock too. But I can’t keep it a secret from you any longer if I could get any help, and maybe if you could arrange some sort of visits on a regular basis with the right psychoanalyst, the whole thing would change around. Again, I’m terribly sorry to give you this shock and pain, but that’s the way it is, and I finally got to the point, after all the rows over the summer, where I felt I really ought to ask you to help me.

Love,

Jeff

P.S. Show this to Dad if you want to, or not if you think it might be too much until he’s really better again. J.

She came to the end and stood as if tranced, without tears, nothing so easy as tears, stood motionless in the sensation of being smashed through every organ, through every nerve, every reasoning cell. Love for him, pity for his suffering, pride for his courage in telling her, horror at

it,

at the monstrous unendurable it—a savagery of feelings crushed her, feelings mutually exclusive yet gripping each other in some hot ferocity or amalgam. She read the letter again. Then only did she begin to cry, but not the ordinary crying, nor she the ordinary weeping woman; it was, rather, a roaring sobbing, of an animal gored. She heard her own sounds, and went to her bedroom door to close it, though there was no one in the apartment

For the first time she thought of her husband, Ken, seemingly well after last year’s stroke, well enough at last to be back at work, but still warned to avoid undue stress, to avoid “overdoing it.” Was he now to hear this? Even Jeff in his own crisis had seen the danger of telling his father now.

Or was Jeff taking this way to ask her not to tell him, as if he were afraid of him, Jeff who seemed afraid of nothing? It was impossible to think of Jeff in fear of anything, he a boy of seventeen, tall, strong, beautiful as all young people are beautiful and beautiful to her in his own personal way because he was her youngest child, because, of the three, he was the only one still at home, still at school, still with all the world ahead of him.

Flashing across her mind came a vision of him with some faceless youth, the two close, the two entwined in some intimacy, and she cried aloud, cried out against it, cried in a devastation she had never known before.

She read the letter once more and pride for his courage overcame her. Had he sat there faltering for words? Had he thought twenty times that he ought to tell them, and fled twenty times from the idea? Her body ached as if she were watching him endure physical torment, and again admiration for his young courage filled her.

She reached for the telephone and then paused. Who knew how private were outside calls to students at Placquette School? Not purposeful snooping by anybody in authority, not at a good progressive school like Placquette, but if there was some student earning extra money at the switchboard, listening in whenever he grew bored? She left the phone, went to the living room and began to write. “Dear Jeff, Your letter just came—” She stared at the bland words. Even if they were different words, instantly conveying what he had to know, he would not receive her letter until tomorrow, more likely not until the day after tomorrow. Suppose he were off there wondering what her reaction would be, fearing it, afraid to count on it, afraid that she would turn away in revulsion?

Across the empty space on the second page of his letter, she wrote a telegram, printing each word as if she herself were spinning out the Western Union tape of capital letters:

PROUD OF YOU FOR LETTER WILL ARRANGE SOONEST POSSIBLE WITH BEST SPECIALIST STOP PHONE COLLECT WHEN YOU CAN STOP LOVE YOU AS ALWAYS MAMA.

She reread her phrases slowly, testing each one for possible revelation to some hostile eye, and then, reassured of the innocence upon the face of each careful word, telephoned it in, specifying that the address be followed by the command

DO NOT PHONE,

and then asking the operator to read all of it back to her. She sat back at last, exhausted.

“You see, I am a homosexual.” She could not contain the violence of rejection within her, not of him, not of her son, but of this that he had told her. Apart from his hot temper, he had always been the most lovable and loving of the children, funny as a little boy, irresistible as a little boy, clever in his wisecracks, good at school, the kind of child whose entire future seemed destined to be great, unlimited, happy.

Now in this one moment of opening and reading a letter—the vision leaped back, of Jeff physically close to another boy, and though she sat, spent and motionless, it was as if she were running in some gasping unbearable need to escape. Not Jeff, she thought, never Jeff.

She looked around the room, as if seeking help, an adviser. It was oddly blank, guarded, though it was a room she had enjoyed for years. She returned to her bedroom; there was something private and comforting here. Near her bed, on a chair pulled close to it like an extra end table, were three cardboard boxes, the top one opened to reveal typed manuscript, the first hundred pages removed from the box and turned face down on the chair seat. These she had read the night before in what she called “flash editing,” the first overall impression before detailed labor might begin on the novel. Her hand went out to the box and stopped. She could not.

The office. She could not go in today, not possibly. She could not talk to Gail even, the secretary she shared with Tom Smiley, could not talk to anybody in a bright offhand office way. She had not gone back to work until Jeff was seven and Don and Margie independent teen-agers, and in the ten years since then, she had scarcely any absences except during the first days when Ken was in the hospital. She loved her job, loved publishing in general, and in particular loved being the only one of the three women editors at Quales and Park not assigned to mystery stories, children’s books or “help” books, cookbooks, gardening books, decorating books. She liked novels that tried to be serious novels, though it was all too rare to work on a manuscript that announced itself almost from page one as a good book, a book she would eagerly read even if another house published it, a book she felt fortunate to work on, doing that amorphous thing called “editing,” which was, she supposed, designed to help the author make his or her book even better.

She reached toward the boxes again but once more her hand halted. Not now, not in this brilliance of pain and shock. She called the office and said, “Something’s come up, Gail, I can’t make it in at all today, I’ll work at home. Do I have a lunch date?”

Her voice was calm, steady; she was surprised to hear it so. “Helena Ludwig? I forgot—please say something’s come up and set it up for any free day next week, would you? … No, not sick, just I can’t make the office until I attend to something that’s important about a letter—oh, skip it. And thanks.”

She actually laughed at the involuted explanation, but the laughing and the calm steadiness were gone when she called her doctor, insisting to his appointment nurse that it was “an emergency of a sort,” insisting, “No, I can’t give you some idea, I’m sorry. I really do have to talk to Dr. Waldo myself.”

A moment later she said, “Mark, it’s Tessa Lynn. Please fit me in today. The most horrible thing has happened, and I have to know whether I can tell Ken or whether it would be too dangerous still. … Three-fifteen. Oh, thanks.”

Five hours, nearly. Should she call Will, her only brother, always so ready to help in a bad time? Not about this, not yet. Perhaps her daughter or her older son? Not yet, not even them. Jeff hadn’t even thought of Margie or Don as he wrote his letter, and it would have to be his decision, whether they were to be told, and when. He was on good enough terms with them, but he was six years younger than his sister and eight younger than his brother, and apart from the age differential between them, there was that wider chasm, that Don and Margie were married and out of the immediate family, Don with two children and Margie expecting her first baby before Christmas. To Jeff they were that other world, grown-ups, as his parents were that other world too.

They were both so normal always, she suddenly thought, and both so normal now, so happily married, and they had been brought up in the same way as Jeff, the same father, same mother, same influences and environment. Then how was it possible that Jeff was not equally normal? He must be, he would prove to be, this was an aberration of some sort that he was going through, terrifying to him, terrifying to her, but no more enduring than a nightmare.

You see, I am a homosexual.

Oh, why had he put it that way, why that simple declarative sentence? If he had written, “I think I am” or “I may be” or “I’m afraid I am”—how much easier it would be. Again she put her hand to the telephone. Whatever Mark Waldo said this afternoon, she still would have to tell Ken. You could not keep an enormity like this from your husband; it would be a kind of betrayal, a denying him his right to know about his son. After all, it was a year since his stroke and it had been a mild stroke, with a nearly full recovery. There was no longer that faint drag when he moved his left arm or left leg, there was scarcely any hesitation in his speech, except when he was agitated. Yet he grew depressed so easily and so deeply; how could she think of telling him?

She understood the depression; he was ten years older than she, in his mid-fifties, and even the mild stroke had told him clearly enough that life was drawing down, had told him of death off there, not so far now as it had always been, not so unbelievable now as it had always been, possible for others of course, but never intertwined with one’s own existence. Poor Ken, with that semaphore forever raised.

Yet Mark Waldo, who had taken care of them all for over twenty years, had made it specific only a short time ago when Kenneth had returned to a full-time schedule. He was no longer to be treated as an invalid, not to be spared the normal stress and worry of living, he was to be treated like a whole person and not like the remainder of a whole person. To treat him in any other way would be demoralizing.

Demoralizing. Moralizing. Words could suddenly take on teeth and claws. Was she not moralizing now? This horror over Jeff and his letter, what was that? This fear of telling Ken, what was that? Was this not all part of moralizing, and hateful because it was? She had always been sure she was free of prudery, of the vicarious prurience that saw sin and wickedness in anything beyond the primer ABC’s of sexual conduct. Particularly when it came to the changing mores of the young, she was not given to moral judgment and disapproval, not even now with the enlarging dreads in this permissive year of 1960. The widening use of marijuana, the widening promiscuity, the reckless speed in cars and on motorcycles, all these new dreads of parenthood she had faced with equanimity. Was it only an assumed equanimity? She had never asked herself that before.