Corvus (18 page)

Authors: Esther Woolfson

The feathers of Spike’s tail, whilst always relatively short, became easily damaged. With difficulty and considerable danger to myself, I’d catch him and, clamping him under my arm, trim his tail feathers neatly with scissors, cutting off the bent and broken ends. When time and mince had dealt with his outrage, he’d celebrate his neat new tail with wild delight, chasing the tidy, shortened version in a whirling, prolonged and dizzying

kazatski

.

His vocabulary grew. His enunciation became more precise. Han would sit in the late afternoons at the table, studying for exams. Spike took a close interest, flying down onto her pages, trying to steal them or rip them up. Han would shout at him, bat him away but he was, as

ever, indefatigable, returning time and again, beginning to lose his temper, muttering increasingly loudly as Han lost hers.

‘Bugger off!’ Han would yell.

‘Bugger off!’ Spike would shriek back, glissading in direct and awesome confrontation down the long wooden surface towards her papers.

(I have a sheaf of cuttings sent by friends with reports of foulmouthed birds: the magpie who, after life with a north-east fisherman, had a wide and well-used vocabulary of vibrant oaths; the parrot who, in colourful, explicit terms, dealt neatly with the pillars of society by swearing in turn at mayor, policeman and vicar.)

The sounds Spike made, apart from obvious words, were both expressive and useful. ‘Eh!’ he’d say. ‘Eh!’

‘Eh!’ Han and I would say to each other, and still do in greeting or agreement, a sort of verbal high-five, an expression of frustration or dubious acceptance. ‘Eh!’

There was ‘oy’ too. ‘OY!’ he’d shout. His ‘Oy!’ covered a multiplicity of purposes, two letters containing a world of history, in both human and magpie terms, an accretion of aggrievedness, outrage, pathos.

One day, when he was a few months old, I came home to what I thought was an empty house to hear a conversation in progress in the kitchen. Standing outside the door, I listened. Although I have tried,

there is no method by which I can render what I heard in words or letters. They were words but not words, a cascade, a trill, a babble of sounds; all the terms of the phonetic dictionary, rolled and lateral and fricative, syllable, consonant and vowel, were there. The voice was enthusiastic, eager in intonation, the rising, falling cadences of speech, the perfect pauses, an amazing mimetic model of speech. The words, for they were words of a sort, were a magpie’s, but the voice was mine. It was the sound of me, conducting a phone call or conversation, every nuance of intonation, every laugh, every mannerism, me, revealed through the conduit of a magpie’s voice. Spike spoke in my voice and, more than that, he laughed with my laugh. I listen to the tape I have of him and hear myself, piped through the vocal cords of a bird.

‘Hello, Spikey!’ the voice yells, with the faintest suggestion of the interrogative in the second word. The sound is ethereal now, otherworldly, almost as if I no longer know whose voice it is. Recently I played it to friends.

‘My God,’ they said, awed, impressed. They looked at one another, wondering if they were about to say something I had never appreciated. I saw them stifle the urge to laugh. ‘He sounds like you,’ they said, as if I might not know.

Pliny suggests that for magpies speech is an obsession, that death results from their failure to enunciate a chosen word, or that they will cheer up after hearing the sound of a forgotten word. Having known Spike, I suspect it may be true.

Whilst most of Spike’s speech appeared to be mimetic, the one

word he consistently used correctly (possibly also in imitation) was ‘what’.

I would go into the kitchen and when I didn’t see Spike, call him, knowing he’d be in one of his hiding places on top of the kitchen cupboards. ‘Spike?’ I’d say.

‘What?’ a voice would shout from above. ‘WHAT?’

It’s reasonable that, were he going to speak like anyone, it would be me. We spent a lot of time together. I talk to all the birds and nothing escaped Spike’s attention, neither sound nor action. I noticed that Chicken too was affected as the impression of words became noticeable in her voice, the faint imprint of ‘hello’ amid her usual calls as I believe she tried to emulate him.

Certain domestic tasks intrigued Spike, the making of bread, the cleaning of any fish, brass- and silver-polishing, when he’d fly down from the top cupboard, shouting greetings and general enthusiasm, to stand beside me on the worktop to watch and contribute his inimitable help, my unhelpful helper. He’d knock over the smaller items I’d polished, then perch himself on the edge of my empty coffee mug to watch the progress of the matter, trying all the while to steal my cloth, hopping with annoyance when I resisted, snapping at me. If I was making bread, he’d make holes in the flour bag. He’d dance about trying to get his beak in to drink the egg I’d beaten to glaze the loaves. When flour, yeast and water had been kneaded into dough, he’d beg and squeak, bearing off his portion to secrete in a place where later, if I got to it before he did, I’d find it, risen and squashed behind my oven glove, in the folds of a tea-towel, behind a cushion on one of the Orkney chairs.

Spike had the advantage over Chicken in his caching activities, since Chicken has never had the opportunities afforded by flight. Spike was able to cache in a multiplicity of sites, whilst Chicken did as she has always done, hid her food under the carpet, whence it was routinely retrieved by Spike, or in her hole in the wall. Chicken regarded the theft with resignation, waiting until Spike was in bed before doing a round of his accessible caching sites to redeem her stolen items. Often, I saw her looking in unexpected places, behind the coal scuttle or under the corner of the fridge, places where I knew she didn’t cache. As all the research I’ve read subsequently suggests, where caching is concerned it takes a thief to recognise the malign intentions of another one. It seemed that, when it came to honesty, there was nothing to choose between rook and magpie.

For them, caching wasn’t a matter of necessity, since they had food available to them at most times (Chicken particularly, because she had her own quarters in my study where Spike was not allowed to go, for the sake of my computer, my papers, the furniture, the lamps, the curtains, as well as in respect for Chicken’s privacy). Spike appeared to cache from a spirit of general busyness, because it was, and is, what corvids do. Spike too, when the chance arose, appeared to do a routine survey of both his and Chicken’s cache sites, checking, removing, replacing. I’d watch his methodical progress. His memory was impressive.

Chicken was never in any doubt about Spike’s potential behaviour. During his infancy I kept them apart because, while we were enthusiastic about fledgling magpies, it might have been expecting too much to assume that Chicken would share our feelings. I could imagine all too well the damage an adult rook’s beak could do to an unfeathered infant. When Spike grew to the size where he was more than able to defend himself, I never left them alone together because by then it was Spike I didn’t trust. Apart from his possible intentions, he was too energetic, too lively for the increasingly sedate Chicken, whom he’d chase round the kitchen table with brisk determination, nipping at her tail. Chicken, a sociable sort of bird, showed only the mildest annoyance at his behaviour, snapping her beak towards him in token protest. They were mutually wary but would on occasion co-operate, sitting together on someone’s knee or the same chair, Chicken occupying the seat, Spike the back.

Konrad Lorenz describes a magpie of his acquaintance as ‘a feathered rascal, lacking any sense of propriety’. Where Spike was concerned this was indubitably the case, although occasional evidence showed at least uncharacteristic moments of an intermittent propriety.

Spike played prodigiously. We gave him toys, a small doll which he dragged about by its bright yellow hair (a good luck troll, donated by Han. I have it still, rendered bald by magpie attentions), a ball which he pushed with his beak and chased. He appropriated from somewhere

the empty spherical container from an air freshener, to which he became unfeasibly attached. He would fly the length of the kitchen carrying something demonstrably too heavy for him in his beak, a wooden spoon, a ruler. He loved to fly, carrying the paper butterfly I had bought for him. He found a tiny blue plastic shoe, a fairy doll with gauzy wings. He’d steal chopsticks, carefully measuring them with his eye before picking them up, perfectly centred, to fly with them across the room. He loved ball games and would play by himself or with whoever would play with him, on the kitchen floor. He and Han would run the length of kitchen to rat room and back again, exchanging the ball, Spike squeaking his enthusiasm, flapping his wings, shouting with what seemed remarkably like joy.

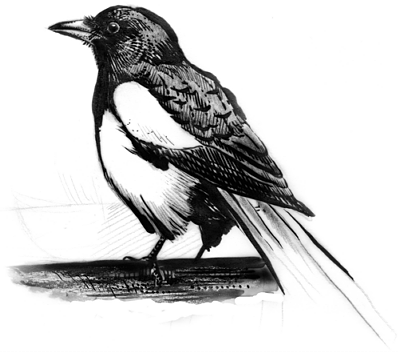

Han, at the time a fervent practitioner in the martial arts, spent time practising kung fu, travelling to competitions from which she returned with ever larger and more fantastical trophies. (The one which accompanied her from Florida when she was about fifteen, her seat companion on a long, cramped flight, was taller than she was. An elaborate, tottering structure of cheap gilt, pilastered and curlicued, topped by an ornament alarmingly like a golden funerary urn, stands still, slightly unsteadily, under a light coating of dust in her room.) It became her habit of an evening, before Spike’s bedtime, to engage with him in a bout of combat, an enterprise that delighted him since he was unfailingly up for a fight. She would initiate the bout by punching the air near his head, one side, then the other, just enough to enrage him, enough to cause him to fly to the top of the fridge, where he’d stand quivering, readying himself, waiting for the moment when he’d attack, his the advantage in proper flight, hurling himself towards her, eyes yellow and protected, squeaking with martial fury, wings a blur and rustle of crisp, bright feather. Wham! Wham! He’d squeak frenetically, shouting random words – ‘Smike! Oy! Oy! Spikey! Hello! Hello!’ – as he attacked her moving fists, diving for her head as she leapt and danced away from him. They spun and fought, Spike launching himself again and again towards her, at her, a marvellous, wild, balletic frenzy of black and white, all the more strange and thrilling perhaps because of the imbalance in size of the participants, their cultural diversity, or the fact that one of them at least had failed to master the important philosophical requirements of the martial arts.

it was intellect that glittered from his eyes