Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (5 page)

Read Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #England, #History, #Royalty

In fact, she had big grey eyes, lustrous skin and an elegant, waiflike figure; she was the darling of the celebrity-obsessed London crowds.

Molly’s father had bequeathed her the curse of breeding without the money to flaunt it. He’d fraudulently entered his baby girl upon the payroll of his army regiment, so that she got a salary unearned.

20

But the scam could not last, and Molly was sent out to earn her living as a palace good-time girl at a very young age. She certainly had all the easy graces of the courtier, having been ‘bred all her life at courts’. She also understood Latin perfectly well, though wisely she concealed her skill.

21

(A lady’s ‘being learned’ was ‘commonly looked upon as a great fault’.

22

)

Uniquely among her frivolous friends, her fellow Maids of Honour, Molly was a good keeper of secrets. She was astonishingly composed and inscrutable for someone so young. Some people inevitably found her polished professional social manner insincere: she seemed to be ‘of the same mind with every person she talked to’.

23

Others found her playful wit cutting rather than amusing, and her jokes ‘extreme forward and pert’.

24

But this smooth surface disguised a young woman who was ‘very passionate’ underneath. ‘I find it beneath me not to be able to disguise it,’ Molly explained, and she hid the essence of herself behind her endless jokes.

25

‘I look upon felicity in this world not to be a natural state, and consequently what cannot subsist,’ she wrote in a rare unguarded moment.

26

Depression was her great secret enemy.

Tonight, for once, pleasure and excitement held it at bay. Unlike the other occupants of Leicester House, Molly could not wait for the evening to begin. The other Maids of Honour had no inkling that she’d recently thrown herself headlong into a mad, bad affair of the heart. The night would bring her once more into the company of her beloved.

*

At about 7 o’clock, going to court began their swaying journeys across London. It would be foolish to walk: the jeers of hostile passers-by, rain and mud were all to be avoided, and the streets of the St James’s district ought certainly ‘to be better paved’.

27

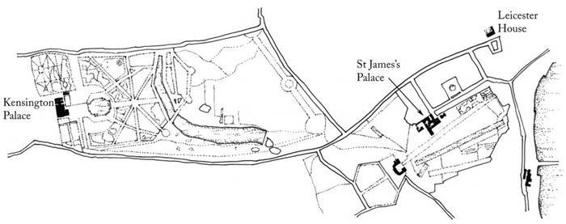

London’s royal residences in the 1720s

A bristling bevy of red-clad Yeomen of the Guard preceded the sedan chairs of the Prince and Princess of Wales as they led the procession of their servants and supporters out of Leicester Fields. Ladies in court dress had to be literally crushed into sedan chairs, ‘their immense hoops’ folded ‘like wings, pointing forward on each side’. To accommodate their ‘preposterous high’ headdresses, they had to tilt their necks backwards and keep motionless throughout the journey.

28

Their destination, the old palace of St James’s, was not particularly impressive. It had been a poorly designed, makeshift mansion for the monarchy since the great palace of Whitehall burned down in 1698. An eighteenth-century guidebook called it ‘the contempt of foreign nations, and the disgrace of our own’; a visiting German confirmed that it was ‘crazy, smoky, and dirty’.

29

Although cramped and unsuitable, St James’s Palace still provided the stage upon which the Georgian court’s most important rituals were performed. To the courtiers its atmosphere was heady, dangerous but absolutely irresistible: ‘full of politicks, anger, friendship, love, fucking and foppery’.

30

Many of the people who weren’t invited to palace parties would have claimed the court was no longer the beating heart of the nation that it had once indisputably been. There was Parliament, now, as an alternative arena for politics. Kings and queens no longer ruled by divine right. Monarchy was on the decline.

And yet, while all this was true, the early years of the eighteenth century were to see a last great gasp of court life and a late flowering of that strange, complex, alluring but destructive organism called the royal household.

The personal was still political at the early Georgian court. The king’s mood, even his bowel movements, could determine the fate of many, as even now he was called upon to make real decisions about the running of the country. His opinion still mattered, and, as contemporaries showed by packing themselves into its drawing room or by begging for jobs as servants, the palace was still a seat of power.

*

As they approached the palace’s lofty red-brick gatehouse, the sedan chairmen carrying Henrietta and Molly in Princess Caroline’s wake had to force a passage through a raucous, torch-lit crowd. Hundreds of people had gathered expectantly to catch a glimpse of the blazing ‘beauties’ arriving in their jewels.

31

Molly Lepell, along with her friend Mary Bellenden, another Maid of Honour, received the loudest sigh of admiration. Although they were not yet twenty, these two were the toast of their generation, and each was as lively and as pretty as the other. Then, as now, society beauties provided the shot of style and celebrity that the masses craved. One popular London ballad promised to expose

What pranks are played behind the scenes,

And who at Court the belle –

Some swear it is the Bellenden,

And others say Lepell.

32

The arrival of the matchless Mary and Molly elicited the kind of greedy, semi-salacious gasp that still runs up and down red carpets today when the stars appear.

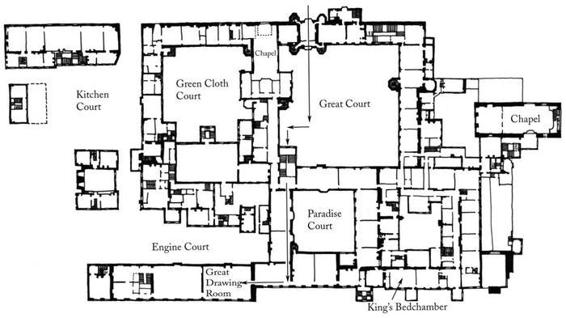

St James’s Palace: ‘crazy, smoky, and dirty’. The courtiers’ route to the drawing room is marked

Through the palace gatehouse lay the Great Court, where soldiers kept guard. It was also called the ‘Whalebone Court’ after the whale’s skeleton, 20 feet long, that was clamped to one wall

33

Here a sea of servants and stationary sedan chairs jostled to drop people off before the fine columned portico sheltering the entrance to the royal apartments. The palace authorities complained constantly about all this traffic blocking the courtyards and passages.

34

Emerging gingerly from their chairs, Molly, Mary and their colleagues were now faced with a wide and grand staircase. Here the scarlet-costumed Yeomen of the Guard acted as security staff and bouncers, refusing entry to the humbly or unsuitably dressed.

There was no official protocol involving invitations. To gain admission you simply had to look the part, so it was vital to swagger and to pretend to be ‘mightily acquainted and accustomed at Court’.

35

One would-be gatecrasher, an enterprising young law student, was turned away at the bottom of the stairs. He went to a nearby coffee house for half an hour, returned refreshed, and discovered that a shilling pressed into the guard’s hand was the key to getting through.

36

The ladies of Princess Caroline’s household were much more readily admitted. They pushed upwards and onwards, taking the tiny, geisha-like steps permitted by their hoops, their gait giving the impression of wheeled motion. They glided through the first-floor guard room, then the adjoining ‘presence’ and ‘privy’ chambers. Their destination was the large new drawing room built by Queen Anne overlooking the park and hung with ‘beautiful old tapestries’.

37

This was the ‘Great Drawing-Room’, where, four nights a week, ‘the nobility, the ministers & c.’ were accustomed to meet, ‘and where all strangers, above the inferior rank, may see the King’.

38

*

Here, at last, is the Georgian court en masse. There is scarcely room to breathe, the air is ‘excessive hot’, and the crush has

prevented many of the nobility even from entering. Chairs are completely absent from the room so that nobody can make the mistake of sitting down in the royal presence.

The courtiers’ colours are pale and sparkling. The penniless poet John Gay, hopeful of a royal patron, arrays himself in silver and blue as he asks himself, ‘How much money will do?’

39

Knights of the Garter wear blue sashes; senior courtiers’ staffs of office are white. The court’s young bloods sport pale-blue silk coats, while their older colleagues have ‘blue noses, pale faces, gauze heads and toupets’.

40

A glittering gown is spotted ‘with great roses not unlike large silver soup plates’.

41

The silver is relieved with touches of crimson: a red sash for a Knight of the Bath; a gentleman in a ‘prodigiously effeminate’ rose-coloured waistcoat; the stout Princess Caroline in pink, ‘superior to her waiting nymphs/ as lobster to attendant shrimps’.

42

Princess Caroline, Prince George Augustus and their party become the centre of attention immediately upon entering. All the most ambitious young courtiers behaved dutifully to the king when he was present, but preferred to pay their court to the younger, bolder, more promising heir to the throne. Peter Wentworth, a junior official, observed that on drawing-room nights, many people were ‘backward in speaking to the King, tho’ they are ready enough to speak to the Prince’.

43

While the king’s party had the greater power, the prince’s had the greater glamour.

*

The younger courtiers now fought to fawn over Prince George Augustus, and drawing-room behaviour was often surprisingly ugly. In the crush people would ‘jostle and squeeze by one another’, shouting ‘pardon’ over their shoulders; it was simply ‘impossible to hold a conversation’.

44

Everyone laughed when Lord Onslow tumbled ‘backward among all the crowd’ and lay sprawling, while another gentleman, ‘drunk and saucy’, had to be ejected for throwing a punch.

45

In his sector of the drawing room, George Augustus spoke one

by one to those courtiers desperately trying to catch his attention. He turned his backside to those he did not wish to acknowledge, a technique known as ‘rumping’. The ‘rumped’ or spurned could console themselves with having earned membership of the exclusive ‘Rumpsteak Club’.

This was boorish behaviour, and Prince George Augustus was not the handsome, charming prince of a fairy tale. His peppery personality and ‘the fire of his temper’ appeared ‘in every look and gesture’.

46

He would let off steam rather comically by kicking his hat, and sometimes even his wig, around the room.

47

A sufferer from high blood pressure, he was subject to ‘constant palpitations about the region of the heart, especially after dinner’.

48

This prince, then, had passion. He made an excellent soldier when his courtiers’ concerns for his safety allowed him to take the field. At the decisive European battle of Oudenarde in 1708, he’d led a celebrated cavalry charge against the enemy, ‘and had his horse shot under him’; military trivia remained his greatest interest.

49