Crazy for God (27 page)

Authors: Frank Schaeffer

“The Gang” in my first feature:

Wired to Kill

, 1985 (Merritt Butrick to the left).

Wired to Kill

, 1985 (Merritt Butrick to the left).

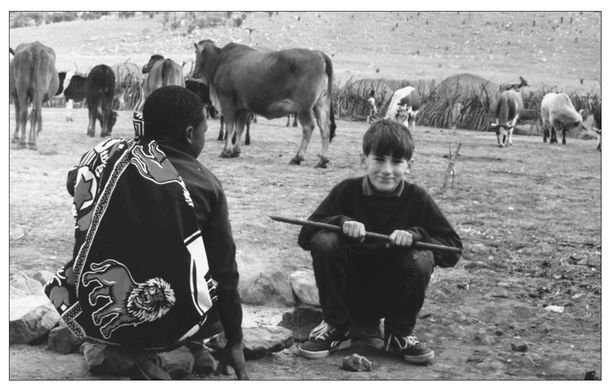

John in South Africa, 1988.

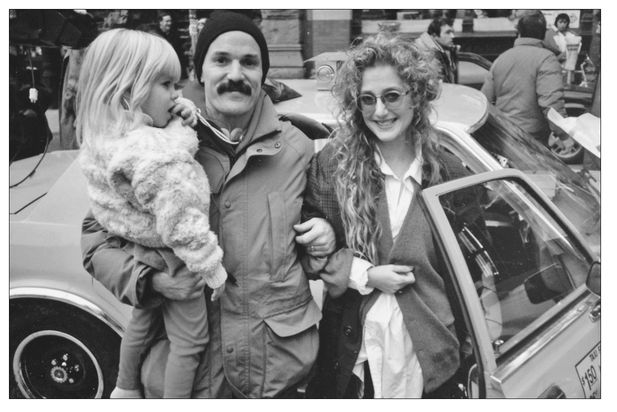

“Baby,” me, and Carol Kane, filming

Baby on Board

in Toronto, 1992.

Baby on Board

in Toronto, 1992.

Wired to Kill

(1986).

(1986).

Baby on Board

(1992).

(1992).

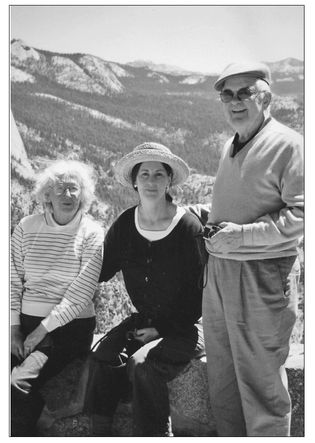

Genie and her parents, Stan and Betty Walsh.

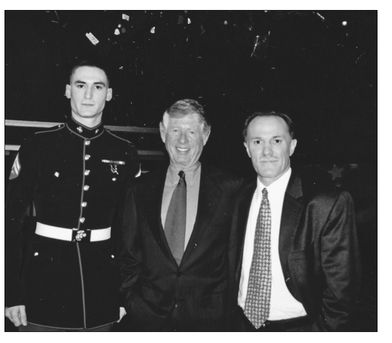

John, Ted Koppel, and me on the set of

Nightline

promoting our book

Keeping Faith.

Nightline

promoting our book

Keeping Faith.

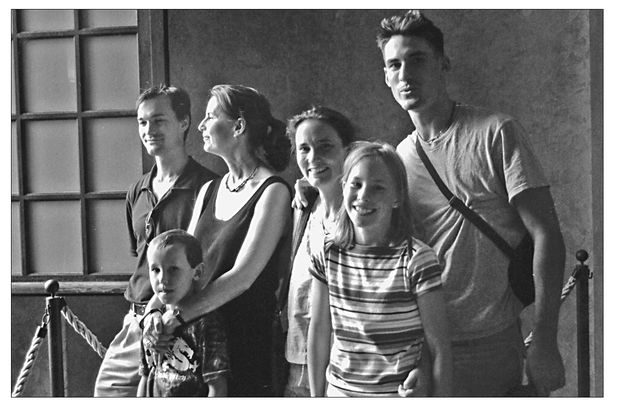

Francis, Ben, Genie, Jessica, Amanda, and John, Parma, Italy, 2004.

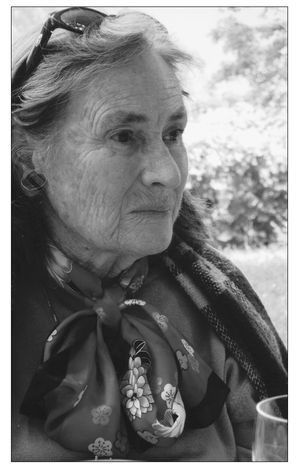

Edith Schaeffer, age ninety-one, at Chalet Tzi-No, Huémoz (2006).

In other words, my parents were no better or worse than most people and went though a few really bad patches. But groupies have to believe in something or someone.

35

I

had become an art- and sex-driven wraith haunting L’Abri and our mountainside. I was in The Work, but not of it. The intrusion of the students, the hurly-burly of the comings and goings, the growing crowds of people who came on Sunday to church in the summer, the constant noise around the house, everything made me hate where I lived—and love it.

had become an art- and sex-driven wraith haunting L’Abri and our mountainside. I was in The Work, but not of it. The intrusion of the students, the hurly-burly of the comings and goings, the growing crowds of people who came on Sunday to church in the summer, the constant noise around the house, everything made me hate where I lived—and love it.

The chalet contained all the swirl of activity any teen could want, but none of the privacy. It was all action all the time. I would retreat to my bedroom or to my studio; do everything I could to carve a little privacy out of the groupings and re-groupings of the students.

I went on raiding parties, cutting through the new students like a particularly hungry tuna through a school of sardines. First and foremost, my target was girls. If one was pretty, I would plot to be near her, see what I could get going. Sometimes I’d find a temporary patron, someone to buy a painting or to introduce me to a gallery owner, or read some of the play I was writing or watch one of my Super-8 movies on the little editing console I set up in my studio.

Lady Edward Montague was one visitor who became a patron. A year or two later, she introduced me to the Frisch Gallery in New York. Later still, Audrey Jadden, who lived

down by Lake Geneva with her husband Bill, two of the best and kindest people I have ever known, introduced me to Mr. Chante Pierre of the Chante Pierre Gallery in Aubonne, outside Geneva. Another set of lifelong and lovely L’Abri friends, John and Sandra Bazlinton, organized a show in London for me.

down by Lake Geneva with her husband Bill, two of the best and kindest people I have ever known, introduced me to Mr. Chante Pierre of the Chante Pierre Gallery in Aubonne, outside Geneva. Another set of lifelong and lovely L’Abri friends, John and Sandra Bazlinton, organized a show in London for me.

Of all my shows, the one at the Chante Pierre Gallery was best. It was a serious gallery, and my work was shown alongside paintings by Miro and Picasso. At the well-attended opening, I almost threw up with nervousness and was also thrilled. It was a wonderful and terrible thing to see my paintings hanging in a real gallery.

At the opening, Chante Pierre introduced me as a young, new, and talented painter, and I watched as “real” (non-L’Abri people), actual art collectors looked at my work. As if by some miracle, several little red dots appeared on the catalogue price list, indicating sales. The feeling I got was like looking over a precipice, thrilled and frightened. And somewhere in my brain, a little explosion went off. It was if I had just heard a whispered message: “You can escape the madness!”

It was the first time that I felt I might have a future, with or without any college degree, with or without a normal childhood. I was going to soon forget that hopeful moment and plunge into my dad’s ministry with a vengeance. But the message of freedom-through-art stuck in my brain someplace. And years later, when I hit rock bottom, that voice reminded me that there are possibilities beyond one’s background. When I would feel most trapped, it would “speak” of freedom.

Some of the workers became my friends, at least for a while. Thirty-year-old English L’Abri worker Os Guinness, for instance, compared notes with me on which girls we thought were the prettiest, which ones I was going to “have a go at,”

and which ones he “fancied.” If he spoke up for one, I’d honor our friendship by not flirting with her, and vice versa. I always envied him. He seemed to get so much further with the girls most of the time, which, given that he was a thirty-year-old eligible bachelor, makes sense now, but didn’t then.

and which ones he “fancied.” If he spoke up for one, I’d honor our friendship by not flirting with her, and vice versa. I always envied him. He seemed to get so much further with the girls most of the time, which, given that he was a thirty-year-old eligible bachelor, makes sense now, but didn’t then.

Sometimes I’d mine the students to find companions for little adventures, like sledding. Every year there was a night when the snow was perfect, packed, icy, and smooth—this was before the days of sand and salt on the road—and I’d take my group with me to Chésières using someone’s car, usually one of the workers, to ferry us back and forth with our old-fashioned wood sleds with steel runners. (We Schaeffers still didn’t have a car, but many of the workers did by this time.)

I’d been sledding since I was barely a toddler, and many of the students had never even seen snow. We would head down the road on some night filled with starlight that made the snow shine. The sleds were designed for one to sit on and steer with your heels. But I lay head-first and steered by leaning this way and that and touching the ground with my hands as rudders. You had to judge the corners right, fly through at the right speed, or pay the price.

We’d have a few girls in the sledding party, and none of the young men wanted to appear slow or inept. So every year there was usually somebody from someplace without mountains who would be showing off, hitting the corners too fast, and we’d have accidents. On three occasions, these were serious. The fact that it was dangerous made the adventure all the more wonderful; not to mention the clear air, the velvet blanket of snow so thick that all the contours of the mountainside, trees, even the thickly covered chalet roofs looked soft and rounded.

The mountains across the valley would be bright, snow

clinging and making everything look huge and close in the starlight, even lovelier if there was a moon. There were so many stars visible and the air was clear, light pollution so low, that even without a moon the snow was bright. When you looked up, it seemed as if there were more sharp glittering stars than gaps between them. The universe seemed friendly and near. Girls looked wonderful, their frosty breaths blooming from red lips, frost-touched cheeks, and wisps of hair peeking from under wool caps, eyes reflecting sparks of starlight.

clinging and making everything look huge and close in the starlight, even lovelier if there was a moon. There were so many stars visible and the air was clear, light pollution so low, that even without a moon the snow was bright. When you looked up, it seemed as if there were more sharp glittering stars than gaps between them. The universe seemed friendly and near. Girls looked wonderful, their frosty breaths blooming from red lips, frost-touched cheeks, and wisps of hair peeking from under wool caps, eyes reflecting sparks of starlight.

Other books

Star Crossed by Emma Holly

This Is Paradise by Kristiana Kahakauwila

Veiled (A Short Story) by Elliot, Kendra

Space Wrangler by Kate Donovan

Eternal by Glass, Debra

Critical Mass by Whitley Strieber

Angel of Auschwitz by Tarra Light

Miranda's War by Foster, Howard;

Countess Dracula by Tony Thorne

Waves of Passion (Wild Women Trilogy Book #1) by Steel, Danika