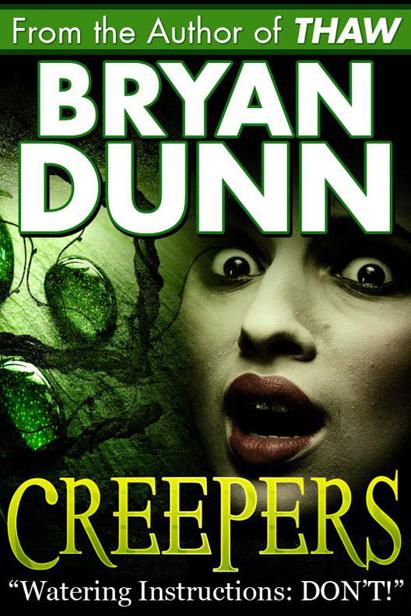

CREEPERS

Creepers

Bryan Dunn

Kindle Edition

Copyright 2011 by Bryan Dunn

Doc Fletcher, an eccentric biologist in the remote Mojave Desert, has finally created the ultimate drought-tolerant plant: a genetically engineered creeper vine. It’s destined to change the world, but not according to Doc’s plans. Instead, this vine has a mind of its own. Mayhem ensues as the residents of Furnace Valley (pop. 16), along with campers at the nearby hot springs, run for their lives— led by wannabe date rancher Sam Rainsford and the nerdy yet gorgeous botanist Laura Beecham, who has come to the desert for a reunion with the father she has never known…

Look for Bryan's Amazon bestseller THAW http://www.amazon.com/dp/B004Q3RME4

To learn more visit:

Bryan Dunn's Amazon Author Page

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

,

Chapter 2

,

Chapter 3

,

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

,

Chapter 6

,

Chapter 7

,

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

,

Chapter 10

,

Chapter 11

,

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

,

Chapter 14

,

Chapter 15

,

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

,

Chapter 18

,

Chapter 19

,

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

,

Chapter 22

,

Chapter 23

,

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

,

Chapter 26

,

Chapter 27

,

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

,

Chapter 30

,

Chapter 31

,

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

,

Chapter 34

,

Chapter 35

,

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

,

Chapter 38

,

Chapter 39

,

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

,

Chapter 42

,

Chapter 43

,

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

,

Chapter 46

,

Chapter 47

,

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

,

Chapter 50

,

Chapter 51

,

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

,

Chapter 54

,

Chapter 55

,

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

,

Chapter 58

,

Chapter 59

,

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

,

Chapter 62

,

Chapter 63

,

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

,

Chapter 66

,

Chapter 67

,

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

,

Chapter 70

,

Chapter 71

,

Chapter 72

Chapter 1

A man pushed aside a large bromeliad, the sweat beading on his face as he reached up and gripped the tip of a fleshy leaf—

ficus elastica

—pulling it down so as to examine its lustrous surface. He bent the leaf to eye level. A silver bead of water rolled across the waxy surface—and just before it lipped off the end, he ducked forward, deftly catching the drop in his mouth.

“Ah,” he said, smacking his lips with delight. He looked and acted like he’d just had a sip of Dom Perignon. His name was Henry Fletcher, Dr. Henry Fletcher to be precise. In school, everyone had called him Fletch. And now, forty years later, friends just called him Doc.

Fletcher was dressed in his “uniform”: khaki shorts, white T-shirt, and dirty sneakers. His bald head was deeply tanned, and a dusting of white stubble covered his face. Humming softly to himself, he took a couple of steps, parted a wall of trumpet vines, stepped through the opening, released the vines—and let the lush foliage press in around him. Standing there, he could almost feel the jungle as it hissed and throbbed, striving up towards the filtered light.

Up ahead, looming out of the shadows, flowering epiphytes beguiled with fleshy, naked-looking petals. And higher up, a hubcap-sized leaf tilted toward the morning light, exposing a stand of bamboo bristling with new growth as its shiny epidermis drank in the life-giving energy.

There was a sudden movement. One of the bamboo leaves twitched, and then swiveled completely around. What had moments ago looked exactly like a leaf morphed into a chartreuse-colored grasshopper. It waggled its antennae—further shedding its disguise—then clambered over to a tender shoot of bamboo and quickly devoured it.

There was a rush of air as a shadow fell across the grasshopper. It twisted its head just in time to see the open maw of a quick little bird—and then it was snapped up. The bird gripped the grasshopper by its thorax and darted to a vine, lighting on a sinewy-looking stalk covered with medusa-like tendrils.

The vine looked strange, almost primordial. Everything about it was menacing and unnatural-looking. The leaves were alien-blood green and covered with tiny scales that looked like the back of a boa constrictor. Raised liver-colored splotches mottled its stalks and roots.

The bird finished its meal and then cleaned its beak by wiping it across the stalk at its feet—the sharp little beak making a

swick swick

sound, like the blade of a knife being worked along a steel. Then the bird fluffed its feathers and began to preen.

A moment later it froze, sensing something was wrong. It tucked in its wings and lifted its head, waiting for any danger to pass.

The air was completely still now as an eerie silence surrounded the bird. A beat, and the silence was shattered by a sharp

rustling

sound—like a rake being swept through a pile of dead leaves. There was another

rattle

—and the bird was suddenly caught in the vine! It kicked and flapped its wings, but it was no use. Something was horribly wrong. Panicked, it began to flail madly about, desperate to escape.

The bird let out an anguished

screech

, unable to free itself, then fell on its side and stopped moving. It was trapped! Something was holding on to it!

In a last attempt to gain its freedom, the bird twisted up and spread its wings, but they wouldn’t work. With every movement, the vine’s wispy tendrils locked tighter and tighter around its body. Then, as quickly it had begun, it ended and the bird stopped moving. There was another sharp rattling of leaves, and the bird disappeared, swallowed up by the strange-looking vine.

Silence.

At the foot of the vine, littered across the ground, dead birds stared vacantly up at nothing. They looked shriveled and dehydrated.

Like something had sucked them dry

.

Chapter 2

A minute later, the air around the vine filled with a loud

crunching

sound as Fletcher brushed aside a cycad leaf and stepped up to the strange-looking vine.

He stared at it for a moment, taking in its height and girth, then reached out and lifted one of the scaly-looking leaves, lightly pinching it between his thumb and forefinger.

Almost reptilian

, he thought to himself.

He released the leaf, reached into a pocket, retrieved a small plastic ruler, and measured one of the vine’s stalks, noting the distance between two leaf nodes. “Remarkable,” he mouthed to himself.

He moved to another section of the vine, lifted a stalk, and repeated the measurement. “Amazing,” he said, this time right out loud. He pocketed the ruler, exchanging it for a Sony handheld recorder.

Fletcher held the recorder up to his mouth, and continuing to study the vine, began to speak into the microphone. “June one. Day five. No water. Growth unabated.”

He clicked off the recorder, then reached out to collect one of the remarkable-looking leaves. As he went to pull it free, he yanked his hand back, yelling “

Ouch!

” Then he thought to himself,

Did that stalk just move?

He held a finger up to his eyes. A perfect little red bead formed on the tip. He popped the finger in his mouth, washing away the blood, then spoke into the recorder. “Note to self, select out thorns on the Fletcher Creeper.”

He reached out to collect another sample—then froze when he heard a mysterious sound.

What the heck was that?

He retracted his hand, keeping his eyes glued to the vine.

Silence, nothing moved.

He continued to wait, but nothing happened. Just as he was about to discount it, the vine came to life and began to shake and rattle, trembling from within. Then, without warning, a stalk shot up into the air, striking him in the center of the chest. Fletcher yelled, pitching back from the vine, and—

The air in front of his eyes turned bright red. Then yellow. Then green. And his ears filled with a skull-splitting sound, “

Squawk-Squawk-Squawk

.”

A second later, a scarlet macaw exploded upwards, freeing itself from the vine’s thorny clutches. It tumbled through the air, somersaulted above his head, and landed haphazardly on a ficus branch. Then it swung its body forward until it was hanging upside down directly in front of Fletcher’s startled face.

“Darwin! Jesus Christ! You scared me half to death.” He bent down, picked up the recorder, dusted it off, and took a step toward the macaw.

“You’re one bad move away from a hatband, Darwin.”

Using his head and outsized beak, Darwin righted himself on the branch and challenged the doctor with another series of ear of earsplitting and unmelodious squawks. Then, as if daring him, Darwin shook his head and fanned his tail, displaying a blaze of gaudy feathers.

Fletcher’s lips flattened into a thin line. Then without warning, he lurched toward Darwin, trying to get his hands around the bird’s feet.

“You’re a feather duster, Darwin!”

Right before his fingers closed around the macaw’s feet, Darwin leapt up. Screeching and flapping his wings, he looked like a tie-dyed T-shirt that had suddenly anthropomorphized and been tossed into the air.

Fletcher lost his footing, pitched forward, and spilled headfirst out of his rainforest and into the hundred-degree heat of a desolate section of California desert—a place called Furnace Valley.

Shangri-la, if you happen to be a rattlesnake.

Fletcher lay in the sand, sprawled on his back, staring up at the cloudless sky. He’d already forgotten about Darwin and was thinking about the vine again.

No water and the thing was growing like a weed!

And just as new thought formed in his head, his concentration was shattered by a loud screeching sound.

Seconds later, Darwin shot out of the greenhouse like a scarlet-colored fighter jet, buzzed Fletcher, and swept into the sky. High overhead, the macaw leveled its wings and made a graceful banking turn as it circled above.

Darwin’s view from four hundred feet up made the Fletcher compound look like a tiny green thumbprint in a sea of brown. The green thumbprint consisted of two buildings with a small pond off to one side. There was the aforementioned greenhouse, and next to that, the main building—or rather, the house that did double duty as Fletcher’s laboratory. The house had a peaked roof, rough-cut redwood siding, and a deep-shade porch that surrounded it on three sides, making it look like something out of an old western.

Fletcher Exotics

. That’s what botanist and geneticist Dr. Fletcher called his operation. He specialized in creating and breeding exotic plants for medicinal and agricultural use.

Five years ago, he had unceremoniously parted company with his academic colleagues after the university where he worked cut funding for his research project—a project that would later produce groundbreaking results in the area of high-yield row crops.

He had pleaded with the administration for more time. Another six months, a year tops, telling them that he was on the brink of having the science hammered out and that the university would soon have something to show for its investment.

The Dean was unmoved and impatient. He demanded results. The

university

demanded results. But Fletcher had stood firm, not willing to rush his work and publish his findings prematurely. They gave him one week to change his mind and get his head right. And when he refused, the administration pulled funding for the entire department.

One week after that, Fletcher severed his relationship with the university—but not before firing off a round of scathing e-mails proclaiming the Dean and his sycophantic minions to be a bunch of four-footed, risk-averse bean counters—bereft of imagination.

In the end, as it turned out, Henry Fletcher had the last laugh. Six months after resigning, he sold a genetically engineered strain of corn to a consortium of ethanol producers for a cool ten million bucks. With one handshake, Dr. Fletcher had become wealthy—but more important than that—now he had all the funding he needed to continue his work, untrammeled by the whims of picayune-minded bureaucrats.