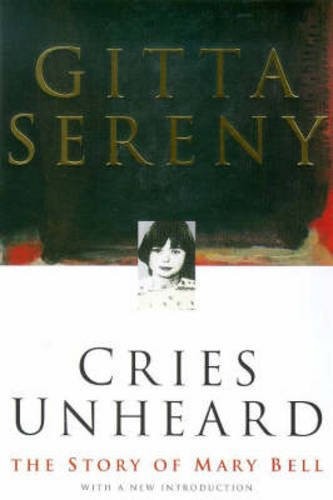

Cries Unheard

Authors: Gitta Sereny

Cries unheard by gitta sereny

In 1972 Gitta Sereny published The Case of Mary Bell, which remains an essential grounding to the case. In 1995, in its most recent reprint, she expressed the hope that one day Mary Bell would talk to her. Now their exhaustive conversations have enabled the author to write Cries Unheard, which, for the first time, reveals the truth of what Mary Bell did and felt, what was done to her, and what she became.

Gitta Sereny has two children and two grandchildren. She and her husband, photographer Don Honeyman, live in London.

Also by Gitta Sereny

The Medallion The Case of Mary Bell Into That Darkness The Invisible Children Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth

THE STORY OF MARY BELL

PAPER MAC

First published 1998 by Macmitlan This edition published 1999 by Papermac an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Ecdeston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www. macmillan co. uk ISBN 0333 75311 9 Copyright Gitta Sereny 1998 Introduction to the Paperback Copyright Gitta Sereny 1999

The right of Gitta Sereny to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Set Systems Ltd, Saffron Walden, Essex Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham pie, Chatham, Kent

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

To Lee Hindley Chadwick the teacher every child should have Pray thee take care, that tak’st my book in hand, To reade it well:

that is, to understand

Ben Jonson, To the Reader, Epigrammes

contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction to the Paperback

Newcastle upon Tyne 1968

1995: The North of England

the trial: december 1968 The Court December 1968 Mary-Reflections The Investigation August to November 1968 Mary Reflections 2 The Prosecution December 1968 Mary Reflections 3 The Verdict December 1968

Mary-Reflections 4 x/ contents

red bank: february 1969 to november 1973 Forgetting Red Bank, 1969 to 1970

143 Betrayals Red Bank, 1970 to 1971

164 Remembering Red Bank, 1971 to 1973 / 180

PART THREE prison: november 1973 TO may 1980 Setback Styal, 1973 / 197 Monotony Styal, 1973 to 1975

220 Giving up Styal, 1975 to 1977

239 Defiance Styal, Moor Court, Risley, 1977 to 1978

263 Transition Risley, Styal, Askham Grange, 1978 to 1980

281

after prison: 1980 to 1984 A Try at Life 1980 to 1984

299 contents

xi

return to childhood: 1957 to 1968 “Take the Thing Away From Me’ - 1957 to 1966

329 A Decision 1966 to 1968

339 The Breaking Point 1968 /

beginnings of a future: 1984 to 1996 Faltering Steps 1984 to 1996 /

Conclusion / 373

Appendix 1 Mary Bell: Documents / 389 Appendix 2 House of Commons Report

399 Appendix 3 Press Complaints Commission Ruling

405

I have only a few people I must thank for their help, for only a few knew of this project.

First and foremost, my gratitude and admiration goes to my publishers, Macmillan, for their courage in accepting to do this controversial book the way it had to be done. Ian Chapman’s and Peter Straus’s unfailing enthusiasm, and from the moment she arrived as Editor in Chief, Clare Alexander’s shining intelligence and warmth smoothed my rocky path till the end.

Perhaps I should thank them above all for giving me Liz Jobey to edit Cries Unheard. I don’t know what to laud most: her understanding of my purposes and principles; her endless willingness to share my problems, or quite simply, her extraordinary talent thank you, Liz.

Rachel Calder is my agent and I hardly know how to express my gratitude to her, and to Marina Cianfanelli, for their unflinching support, at all hours of day and night. I feel very lucky to have them at my side.

I have also had throughout this difficult period the advice and counsel of Allan Levy QC, who knows more about children and the law than almost anyone I know; he too has become a friend.

I think I can say the same about the people whose names I’m not allowed to mention: the two probation officers who speak in the book who, much more than supervising Mary, gave her warmth and encouragement at some of her worst moments; the couple who worked at Red Bank when Mary was there and who shared with me so much of their knowledge; the live-wire prison governor whose sense of humour and passion for human beings made the hours we spent together pass like minutes, and finally “Chammy’ whom Mary remembers with love and I thank with affection.

xiv/ acknowledgements

I thank Clan Bar-On and Virginia Wilking for lending me their wisdom, Professor Guy Benoit for giving me so generously of his time, Angela and Mel Marvin in New York and Hanneri and Fritz Molden in Alpbach in the Tyrol for being our dear friends. And thank you to Melani Lewis who looks after our home-I don’t think I could have managed without you.

A special thanks, of course, to my son Chris and his wife Elaine for their unfailing encouragement and their love.

It seems to me that instead of yet again, in yet another book, thanking my husband, Don, he and I can thank each other that this book is the one coming out in our fifty-first year together.

My last word of thank you, finally, is to my daughter Mandy who, though several years younger than Mary, was fully aware of her ever since I wrote The Case of Mary Bell. With this book now, she has immeasurably helped me, with her energy, her intelligence and understanding for what I am trying to do, and last but by no means least, with her compassion for Mary.

Many people who pick up this new paperback will have heard about this book a year ago. For two weeks before serialization of Cries Unheard was to start in The Times last May, three weeks before it was due to be published, and so without the least idea of either the content or the purpose of this book, an unprecedented paroxysm of tabloid media wrath, which was to last six weeks, was unleashed against the person whose story this book tells and therefore, of course, against the book and its author.

By now, of course, all this has changed: there have been many serious reviews, innumerable debates on radio and TV, many statements by professionals supporting the book’s purpose, and questions and answers in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Nonetheless, I want to be sure that anyone who turns to this page knows from the start what my purpose is and always was.

Cries Unheard is about the life of an English girl born in 1957, who at the age of eleven killed two little boys of four and three and, convicted in a Crown Court of manslaughter, was sentenced to detention “or life. By the time in 1996 when she tells me her story of a suffering childhood and adolescence, she is thirty-nine. Mary Bell, for that was her name, was English. But she could just as well have been Belgian, French, German, Norwegian, Swedish, Japanese or American -for in all these countries young children have been similarly hurt and in recent years have, in turn, I believe, hurt others.

Indeed, juvenile crime robbery, arson, assault with weapons, rape, manslaughter and murder (often committed by ever younger children) has increased to such an extent in all of the western world that many enlightened people are asking serious questions.

Xvi/ introduction TO THE paperback

Have we any idea, thinking people are asking sociologists, psychiatrists, lawyers, judges and serious journalists, why children are becoming so violent? Do they understand the consequences of their actions? Do they know that death is final? And to what extent is their exposure to sex and violence in society, to what extent indeed are people in their immediate environment such as parents or parent substitutes, to blame?

It was in a search for these answers, basing my exploration on the life and the experiences of one such former child whom, with her consent, I quite deliberately used as an example or a symbol of many others, that I wrote Cries Unheard. The central account here, the story as Mary Bell told it to me, is not intended by me or her to be the story of her crimes, but to be rather a document which might serve as an incentive to all of us who care about children’s well-being to make their lives better. Whether it be parents or young would-be parents, neighbours, social workers, teachers, judges and advocates, police or government officials, if Mary’s painful disclosures of a suffering childhood and an appallingly mismanaged adolescence in detention can persuade us to learn how to detect young children’s distress, however hidden, and hear their cries, however faint, we might eventually be in a position to prevent children from offending rather than as is essentially happening all over the western world both inappropriately prosecuting and in aptly punishing them when they do.

Mary Bell, an attractive intelligent woman, stands now, as I am writing this three and a half years after the project began, at the cusp of middle-age. As her story demonstrates very clearly, thirty years ago when she committed the awful acts of killing the two toddlers, she was at a breaking point after years of virtually unrelieved abuse and distress at the hands of her mother. This is not an excuse, either in my eyes or hers. There is no excuse, but there can and need to be explanations. For her, who has always feared there was some

fundamental flaw in her which made her mother hate her, even the relative introduction TO THE paperback /XVii insight she has now gained about the effects of her disastrous childhood is not enough of an explanation. But for me it is, because I am convinced that children are born ‘good’ but, as happened to Mary in 1968, they can some sooner, some later be driven to this ‘breaking point’ where good and bad no longer have any meaning.

As a rule, children sentenced to detention in Britain are intended to disappear into anonymity: care or prison personnel are under obligation not to discuss them with outsiders or even to divulge their presence wherever they are. This excellent rule, although theoretically it certainly applied to Mary Bell, never worked in her case because her mother used every opportunity, every visit she payed to her for years, to sell sensational stories to the local press, who in many instances sold them on to the nationals. The result was not only that Mary’s already very difficult imprisonment was immeasurably worsened because of the staffs as well as her fellow inmates’ fear of these indiscretions, but that t^e tabloids and popular magazines, both British and foreign, were continuously kept aware of her: quite aside from the obvious tabloid interest in a notorious and exceptionally pretty young female prisoner, she was and this was meat and drink for the tabloids a potential source for an exposure story about prisons, wardens and inmates. Thus when they learned in 1979 of her transfer to an open prison, and her assignment to the outside-prison work programme, which is sensibly organized in preparation for prisoners’ release, the media pursuit began which was to become a nightmare for her and, as I will show, but for the essential kindness of local authorities and the British public could eventually have led to tragedy. Over the next sixteen years she not only rejected every one of the more often than not six-figure offers for her story, but also, every time they came close to finding her, time and again moved house, even to other areas of the country, in an effort to protect the anonymity of her family, above all her child. Consistently supported by sympathetic probation officers and unprecedentedly strong injunctions against media interference issued by the Official Solicitor, who has been Mary’s daughter’s guardian since her birth in 1984, the protection in fact worked until April 1998.

xviii/ introduction to the paperback

The Court’s injunction not only applied to the tabloids, but equally to me. And the book on which Mary and I agreed to collaborate in November 1995 (a decision which was entirely hers and mine to make and for which all the problems she or I might have to face were carefully considered) would have been impossible to undertake without the knowledge of the Court and the Home Office’s Lifer Unit the department in charge of released prisoners on licence. (Under British law, released prisoners who have been convicted of murder or manslaughter remain subject to recall to the end of their lives. ) Neither of these government departments were in a position to forbid Mary to co-operate on a book: once released she was theoretically a free agent. But nor would either my British publishers or I have gone into this project without a degree of assurance that there was no legal objection to it. The Home Office, familiar with my first critical book on the subject of trying young children as adults. The Case of Mary Bell, published in 1972, made clear that they were not happy about the prospect, but could do nothing about it. They are in charge of both Children and Prisons and they were no doubt aware that Mary Bell would report on her treatment by the authorities since her incarceration at the age of eleven and that much of this was unlikely to be positive. Obviously, they had been informed by the terms of the proposed contract and knew as of March 1996 that, upon my insistence, Mary would receive a part of the advance on royalties my British publishers, Macmillan, had offered me.