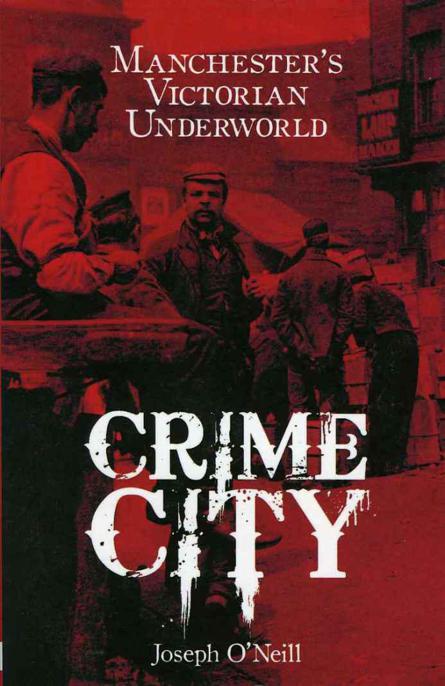

Crime City: Manchester's Victorian Underworld

Read Crime City: Manchester's Victorian Underworld Online

Authors: Joseph O'Neill

First published in March 2008 by Milo Books

Copyright © 2008 Joseph O’Neill

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 903854 77 8

eISBN 978 1 908479 12 9

Typeset by Jayne Walsh

Printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berkshire

MILO BOOKS LTD

The Old Weighbridge

Station Road

Wrea Green

Lancs PR4 2PH

United Kingdom

www.milobooks.com

Contents

10 The Good, the Bad and the Dangerous

Prologue

E

very city gets the criminals it deserves. Manchester in the second half of the nineteenth century was no exception.

The city was a furnace, forging a new world and a new man, transforming all those poured into its great crucible. There had never been anywhere like Manchester and this unique place created a unique underworld, unlike London’s and totally different from those of other emerging industrial centres. The city sucked in people not only from the surrounding countryside but also from every impoverished and persecuted country in the world and flung them together into an explosive mix.

To understand the Manchester underworld at this time you must first understand Manchester. In particular you must know something about the Manchester Irish. They were the city’s largest group of immigrants and throughout this period many blamed them for all the city’s ills, especially its crime.

In reality Manchester’s underworld rested on more than Irish immigrants. Its foundations were five stout piles driven into the bedrock of the city: the rookeries, the pub, the pawnshop, the lodging house and the workhouse. These were the criminals’ natural habitat, where they flourished in good times and foundered in bad. They were also the places where they rubbed shoulders with the poor – respectable and not so respectable. Though these five pillars underpinned the Manchester underworld they were by no means the exclusive preserves of criminals. Many of those living in the lodging houses of the rookeries, for instance, were decent people struggling against overwhelming odds. The pub was a small oasis of delight in the lives of the honest poor. For most working people the pawnshop was all that stood between them and the workhouse. But the criminal world ran parallel to that of the poor. Like the shoreline and the sea it was often impossible to say where one ended and the other began.

Ranged against this amorphous threat stood the police, the courts and the prisons. Manchester boasted a number of famous policemen, masters of their profession. Two of the most celebrated, Jerome Caminada, a detective with a national reputation, and James Bent, a decent and humane man, known for his work with the Manchester poor, gave long and distinguished service. Yet, despite their efforts and those of many other dedicated peelers, the police laboured under many handicaps which severely hindered their fight against crime.

Similarly, the courts did little to stem the tide of crime, especially violent crime that flowed unchecked through the streets of the city. The notion that nineteenth century courts inflicted savage retribution on those guilty of even minor misdemeanours does not stand up to scrutiny. As we shall see, the courts in Manchester were often indulgent of those guilty of violence and other serious crimes.

Strangeways, whose grim profile gives the city a skyline as distinctive as that of Paris, then embodied the most advanced thinking in penology. But it held no terror for the criminal. Like the workhouse, its inmates enjoyed a life better than that outside.

Respectability was far more effective than the police, courts and prison in containing crime. It kept poor people from drifting into the ways of the criminals they lived with. But chiefly the shortcomings of the underworld kept crime in check. There were famous criminals in Manchester during this period whose imagination, audacity and inventiveness made them a major threat to the city. But they were the exception.

For the most part Manchester criminals were like all criminals – pathetic, inadequate individuals. More than any other group, the murderers demonstrate this. Few killed as part of a criminal strategy. Some were inept criminals, killing for piffling gain. Most did it because it was the only way they could express their rage, frustration or resentment. They lived when boot and fist were the idiom of anger.

And Manchester was an angry city. It was not a city, more an assault on the senses. There had never been anywhere like it.

1

Manchester

A New World

Manchester made the world. Our industrial past, the chrysalis from which a city of penthouses and tapas bars is now stirring into existence, was the birthplace of industrial society. Manchester made the world in its own image and likeness. The city was the prototype, the herald of a new world that changed human existence more than any war, revolution or invention before or since. It was the most dynamic metropolis in the country. Not only was it at the heart of the cotton industry, it was the hub of a worldwide trade that was Britain’s biggest earner.

But Manchester’s birth was no easy delivery. The city came into the world screaming and those who witnessed it did so with fascination and horror. Blood-stained streets were a permanent feature of the city. For decades Manchester was the arena for a clash between the two classes spawned by the Industrial Revolution: the new, callous rich and the dispossessed, angry poor. The Peterloo Massacre of 1819 confirmed this in the popular imagination. When the local elite set the yeomanry on a peaceful demonstration, killing innocent women and children, their flailing swords secured the city’s place in the annals of class conflict. Ten years later the violence with which the army crushed rioting in 1829 further heightened tensions in the city and the bitterness persisted in less sensational incidents throughout the century. For instance, the MPs elected in 1832, Mark Phillips and Poulett Thompson, were caricature reactionaries – hostile to any improvement in factory conditions, opposed to the extension of the franchise and adamant that the poor must be kept in their place.

As well as the battleground of bosses and workers, the city was also the focal point for the force that was challenging the old establishment – the anti-Corn Law League. Manchester was also the centre of Nonconformity, the vibrant ideology that eschewed the Anglican landowners’ Church and equated hard work with doing God’s will.

It is obvious why everyone seeking to understand what was going on in the world came to Manchester. Though this monstrous creation baffled them, they instinctively sensed that it was of monumental importance. In 1843 Thomas Carlyle, Victorian England’s most authoritative commentator, described the city as ‘wonderful, fearful and unimaginable’. He sensed the city was transforming the world, describing it as ‘the type of a new power on the earth’.

Charles Dickens and Benjamin Disraeli and every other commentator trying to make sense of what was happening to the world regarded Manchester as a living experiment. What they saw was of monumental significance. When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels evolved their theories of how the capitalist world would develop, it was while they were walking along Oxford Road and drinking in the Crescent pub in Salford. The horrors and injustices they cited were Manchester’s horrors and injustices. When they wrote of a dehumanised race, reduced to units of labour and deprived of all dignity, they were talking about the people of Manchester.

Ancoats, at the heart of the city, was Manchester in microcosm. It was the pumping heart of the industrial nation, the first industrial suburb. Its narrow streets, walled in by mills which became the model for the American cotton industry, echoed to musical Italian, harsh German and nasal Polish, as well as the flat Manchester vowels. Its mills were the most advanced in the world – the Murray Mills were the first to use steam power. They formed the backdrop against which the industrial working class came into existence. The names of these streets – Cotton Street, Loom Street, Silk Street, Bengal Street – are redolent of an age when Britain was the world’s only superpower. There could be no starker contrast than that between the Empire’s opulence and Ancoats’ squalor.

More than anywhere else Manchester epitomised the liberal spirit of the age – parliamentary reform, free trade, the Charter. The city stood for the rising middle class who wanted to replace the landed aristocracy as the country’s rulers. Yet there was nowhere where the ‘dark satanic mills’ were more a reality. These mills gave Manchester its key place in British industry. Britain’s, and the world’s, greatest industry during the nineteenth century was cotton. For the best part of a century, cotton was king and Manchester was Cottonopolis. The mills of Ancoats, Harpurhey and Strangeways led the industry. Most are now gone, the rest turned into apartments for the aspiring young. Yet their image has passed into the national consciousness, largely because L.S. Lowry painted these inner city streets when cotton, like a consumptive, still had the bloom of health though it was in its death throes. Lowry captured an enigma – individuality overlaid with a grim uniformity.

Nineteenth century Manchester was also an enigma: the precursor of a new world wealthier than any preceding civilisation, one of the most important urban centres in the world and the powerhouse of the liberal ideas that were transforming society. Yet it was also a city awash with crime, vice, drunkenness, poverty and violence.

It is no wonder Manchester exercised such power over the nineteenth century mind. It attracted all manner of inquirers – economists, historians, social investigators and curious foreigners – and most recorded their impressions. There are as many descriptions of the city as there were visitors, but they agree on three things: Manchester was ugly and it was evil. But most of all it was dangerous.