Crime Time: Australians Behaving Badly (7 page)

Read Crime Time: Australians Behaving Badly Online

Authors: Sue Bursztynski

Tags: #Children's Books, #Education & Reference, #Law & Crime, #Geography & Cultures, #Explore the World, #Australia & Oceania, #Children's eBooks

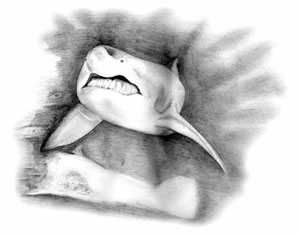

THE SHARK ARM KILLING

O

n Anzac Day in 1935, people enjoying the public holiday with a visit to Sydney’s Coogee Aquarium got a rather special treat. A huge tiger shark on display suddenly vomited up a human arm.

The shark hadn’t actually eaten the arm. It had swallowed a smaller shark, which had swallowed the arm. Then it had been captured for the aquarium.

There was a lot of excitement over the matter. The story and the photo of the arm were in all the newspapers. It came out that no shark had eaten the victim. The arm, which had a tattoo on it, had been cut off its body with a knife. Clearly, someone had committed murder. First, police had to find out whose arm this was.

This didn’t take long. The tattoo helped. A man called Smith saw the photo in

Truth

newspaper and said the arm belonged to his brother James. James Smith had been a petty crook, so the police had his fingerprint on files and were able to confirm that it was his arm.

They visited James’ wife, who told them that her husband had gone out fishing on 7 April and never returned. A forger friend of his, Patrick Brady, might be able to help them, she suggested. People in the area near Brady’s home in Cronulla had seen the two men together. The real estate agent who rented Brady his house said that some stuff was missing from it. Heavy stuff. A big tin storage case (nearly big enough to hold a body, perhaps?), an anchor and some lead window weights had all disappeared.

When the detectives found Patrick Brady, he said that he’d seen Smith with two others, one of whom was a man called Reginald Holmes. Holmes was a boat builder. A boat which Smith had helped to build had sunk. Holmes had lost money on it and was not happy with Smith. Not happy at all. They arrested Brady anyway, and then went to find Holmes.

When the detectives reached McMahon’s Point, where Holmes lived, they found that Holmes had decided to kill himself in one of his own speedboats. As the boat sped through Sydney Harbour, he put a gun to his head to shoot himself, but messed up. He did manage to blow himself out of the boat, bleeding but relatively unharmed. Climbing back aboard, he tried to escape from the police, but after a thrilling two-hour chase, he finally stopped at a place called Watson’s Bay and gave himself up. He said he hadn’t realised it was the police chasing him. Nobody believed that. He was arrested.

As he was injured, Holmes was taken to hospital where the police put him under guard. A few days later, he told them that Patrick Brady had murdered James Smith and had threatened to kill him, or have one of his friends kill him, if he spoke to police about the murder.

Whether or not this was true, we may never know. Holmes was going to speak as a witness against Brady at an inquest, beginning on 12 June. The prosecution was relying on him.

Perhaps Brady really did threaten to have Holmes killed, because on the morning of 12 June, someone shot Holmes as he was driving his car under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Two men were arrested for Holmes’ murder, but there wasn’t enough evidence to convict them and they had to be released.

With no witness, now that Holmes was gone, no evidence and no body, the police had to release Brady.

The shark arm mystery has remained a mystery, even to this day.

DID YOU KNOW…?

In 1992, James Finch, who had served time for the 1973 Whiskey Au Go Go firebombing, made a truly weird request from his home in England. While he’d been in prison, someone had sliced off the top joint of his little finger. It was in a jar in the prison’s museum. He wanted it back.

SNOWY ROWLES

THE PERFECT MURDER

W

hat would be a crime novelist’s worst nightmare? Many would say that what they fear most is that someone will use their books to help commit the perfect crime.

Arthur Upfield, a popular crime writer of the 1920s and 1930s, author of the ‘Bony’ mysteries, found out how this felt.

Upfield had had some novels published already in 1929, when he went to work as a boundary rider on Western Australia’s Rabbit- Proof Fence.

He was working on a novel,

The Sands of Windee,

and wanted his fictional detective to try to solve a murder without a body. He hadn’t come up with an idea yet for how this could be done and asked his workmates for suggestions. How, he asked one night at the campfire, could a murderer get rid of a body completely?

The answer came from a man called George Ritchie. George suggested that the body could be burned first. There would be bits of bone left over, but those could be sifted out from the ashes. The ashes could be scattered and the bones pounded down. What was left could be dissolved in acid.

It was a great idea, Upfield agreed. Perhaps it was

too

good. After all, the detective had to be able to solve the mystery in the end! He asked Ritchie to think about it and offered a pound as a reward for a flaw in the plan that would help the detective solve the crime.

Unfortunately, one of the other workers was a travelling stockman called Snowy Rowles. When Ritchie mentioned the problem to him one day, he started to think – and he wasn’t thinking about a way to earn that pound, either!

Soon after, Upfield, Ritchie, Rowles and some others were discussing the problem again at Camel Station, where they all worked. Still no one had thought of a flaw. That was in October.

In December, James Ryan and George Lloyd, two men travelling with Rowles, disappeared. A prospector called Yates mentioned that he’d seen Rowles driving Ryan’s car. Rowles had told him that the other two were walking through the scrub, but Yates hadn’t seen them.

On Christmas Eve, Rowles, who still had the car, mentioned to Upfield that Ryan had decided to stay in Mount Magnet and had lent him the car. He told someone else that he’d bought the car.

In May 1930, a man called Louis Carron left his job at Wydgee Station with Rowles. No one ever saw him alive again, yet Rowles was seen cashing Louis’ pay cheque. But Carron had friends who were worried for him, because he had been keeping in touch and nobody had heard from him in a while. Rowles had been seen in Carron’s company. When Rowles didn’t answer a question sent to him by telegram about Carron, the police were called.

By this time, everyone had heard of the ‘perfect murder’ from Upfield’s new novel and the police found that not one, but three men had last been seen alive hanging out with Rowles. Detectives found some of Carron’s belongings at a hut along the Rabbit-Proof Fence, including a wedding-ring which was definitely his. His wife had had it recut and the jeweller had accidentally soldered it with a lower grade of gold than the rest of the ring.

Rowles was arrested. It turned out that he was a burglar called John Thomas Smith, who had escaped from jail. That meant they could keep him in prison while checking out the evidence.

Upfield had to be a witness at the trial and meanwhile, the newspaper reports were published side by side with scenes from his book. No doubt it sold plenty more copies of the book for him!

Rowles was found guilty of the three murders and hanged in 1931.

As for Arthur Upfield, he not only had a great plot for that book, but he used the wedding-ring story in another book. No more giving ideas to murderers!

DID YOU KNOW…?

Better late than never… In 2008, 86 years after Colin Ross was executed at the Old Melbourne Gaol for the rape and murder of twelve-year-old Alma Tirtschke, he finally was pardoned by the Victorian government. Unfortunately, although he almost certainly didn’t commit the crime, the sentence can’t be overturned, because that would legally require a retrial and it’s a little hard to retry a case like this after nearly a century.

THE PYJAMA GIRL

I

n September 1934, a farmer leading his prize bull home along a road near Albury found the body of a woman dressed in yellow silk pyjamas. Police had trouble identifying her. They couldn’t even check dental records, because there was a bullet lodged in her jaw. Someone had shot her and then tried to burn her.

Because she couldn’t be identified, the ‘Pyjama Girl’, as she became known, was taken first to Albury hospital to be put on ice, then to Sydney University, where she was put into a tank of a preserving liquid called formalin.

After a few months, police interviewed an Italian waiter, Tony Agostini, who had lived in Sydney before moving to Melbourne. His wife, Linda, had disappeared around the time the Pyjama Girl turned up. He looked at the photo of the dead woman and denied it was his wife. He said that Linda had left him about a year ago and he had no idea where she was.

At that point, the police didn’t take it any further.

For ten years, the Pyjama Girl lay in her formalin bath at the university. Then the New South Wales Police Commissioner, William Mackay, re-opened the case. He arranged for the Pyjama Girl to be removed from the tank. Make-up artists and hairdressers made her look presentable and, hopefully, like she had during her life. Sixteen people who had known Linda Agostini were asked to take a look at the body. Seven of them said they recognised her.

Mackay knew Tony Agostini personally. He was a waiter at Mackay’s favourite Sydney restaurant, Romano’s, where he had been working since moving from Melbourne.

He rang the restaurant and asked to speak to Agostini. He told him what had happened.

Tony broke down and confessed. He said that Linda had made his life miserable. She had a very bad temper and got especially violent after she had been drinking. She drank often. One night, he said, he had woken to find her standing over him with a gun. He had wrestled with her for the gun, to stop her shooting him. The gun had gone off by accident while they fought and she had been killed.

Agostini said that he panicked. Instead of contacting the police, he had put her body in his car and driven through the night, along the Hume Highway towards Albury. He had thrown the body into a ditch, poured petrol on it and tried to burn it. It had begun to rain, so the body didn’t burn completely. Agostini said he’d returned to his car and driven back to Melbourne.

When he was put on trial, the jury didn’t take long to reach a decision. He wasn’t convicted of murder, but of the lesser crime of manslaughter, because the death wasn’t intended. He was sentenced to six years of hard labour, but he served only four before he was deported to Italy, where he lived the rest of his life.

There are some strange bits to this story. Tony and Linda were living in Melbourne when this killing was supposed to have happened. Albury is on the border of New South Wales and Victoria, hundreds of kilometres away from their home. Why drive all that way to dump a body?

When asked what he wanted done with the body, after conviction, Agostini said he didn’t care, because it wasn’t his wife.

A Sydney woman called Jeanette Rutledge had been saying that the dead woman was her daughter, Anna Philomena Morgan, but she had mental problems and police didn’t believe her.

Was

it Anna Philomena Morgan? If so, what

did

happen to Linda Agostini? If her husband hadn’t killed her, why did he say he had? And then why did he change his story? Right until he left for Italy, he denied having killed the Pyjama Girl. He was in trouble with an Italian criminal organisation, the Camorra. Perhaps he felt safer in jail than out!

These days, it might be possible to do a DNA test on any living relatives Linda might have, to see if the body was hers. Otherwise, we may never know.

DID YOU KNOW…?

Archaeologists digging at Melbourne’s former prison, Pentridge, found some bones that probably belong to the bushranger Ned Kelly. The skull was missing, as it was stolen in 1978.