Crimes Against Liberty (34 page)

Read Crimes Against Liberty Online

Authors: David Limbaugh

There was no mistaking the president’s harsh tone toward the bankers. One attendee commented, “The only way they could have sent a more Spartan message is if they had served bread along with the water. The signal from Obama’s body language and demeanor was, ‘I’m the president, and you’re not.’”

11

Sounds familiar, does it not?

When the subject turned to the salaries and bonuses, one CEO explained, “We’re competing for talent on an international market.” But Obama, the self-described “listener,” was uninterested. He interrupted them and warned with his signature haughtiness, “Be careful how you make those statements, gentlemen. The public isn’t buying that. My administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks.” If that was true, it was only because Obama had stoked the flames against banks and corporate executives in the first place.

More than a half year later, in December 2009, Obama was still blasting Wall Street bank bonuses, declaring on CBS’s

60 Minutes

, “I did not run for office to help out a bunch of fat cat bankers on Wall Street. The people on Wall Street still don’t get it. They’re still puzzled why it is that people are mad at the banks. Well, let’s see. You guys are drawing down $10 (million), $20 million dollar bonuses after America went through the worst economic year in decades and you guys caused the problem.” He also accused the banks of “fighting tooth and nail with their lobbyists” to oppose financial regulatory control .

12

But once again, “excessive CEO salaries” were only a problem for certain bankers unconnected to Obama; it came to light in February 2010 that government-run GM was providing its CEO, Ed Whitacre, a pay package valued at $9 million—a package approved by U.S. Treasury pay czar Kenneth Feinberg.

13

SQUEEZING THE “FAT CATS”

In a December 2009, meeting with the CEOs of large banks, Obama all but ordered them to increase their loans to small businesses and their assistance to troubled homeowners. In a statement, he again referred to the financial collapse being “a predicament largely of their own making, oftentimes because they failed to manage risk properly.”

But in fact, with its myriad regulations and programs pressuring banks to offer mortgages almost regardless of the recipient’s ability to repay, the government was a greater contributor to the crisis than “Wall Street.” Both parties, though Democrats far more than Republicans, embarked on this loose lending policy, placing their “good intentions” above good financial sense, and forced banks to make uncreditworthy loans in the name of compassion.

But when the Bush administration warned as early as 2003 of the systemic risks posed to the entire economy by the expansion of Fannie and Freddie and recommended the creation of a new federal agency to regulate them, Democrats, such as Congressman Barney Frank, would have none of it. Frank said that critics “exaggerate a threat of safety” and “conjure up the possibility of serious financial losses to the Treasury, which I do not see.” Frank sneered at the idea that the government’s lending policy had been too liberal, saying it had “probably done too little rather than too much . . . to meet the goals of affordable housing.”

In June 2004, seventy-six House Democrats, including Barney Frank and Nancy Pelosi, sent President Bush a letter defending Fannie and Freddie and insisting that “an exclusive focus on safety and soundness” would likely come “at the expense of affordable housing.” Similarly, in 2007 when the Bush administration discovered some $11 billion of accounting errors on the books of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and demanded a “robust reform package” for these companies as a condition to their expanding their mortgage portfolios, Senator Chris Dodd, chairman of the Banking Committee, scoffed that Bush should “immediately reconsider his ill-advised” demand. Dodd continued this reckless obstinacy into July 2008, when he pronounced that Fannie and Freddie were “on a sound footing.”

14

An analysis by George Mason University economics professor Lawrence H. White found the financial crisis and ensuing recession were not the result of “financial deregulation and private-sector greed,” but “misguided monetary and housing policies: . . . the expansion of risky mortgages to underqualified borrowers . . . encouraged by the federal government.” Additionally, “the government-supported mortgage lenders, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, grew to own or guarantee about half the United States’ $12 trillion mortgage market.” This caused monumental distortions in the mortgage market because the guarantees artificially eliminated the risk of purchasing bad mortgages, thus catalyzing their rapid expansion. Congress exacerbated the problem and virtually guaranteed a meltdown by pushing Fannie and Freddie to continue to “promote ‘affordable housing’ through expanded purchases on nonprime loans to low-income applicants.”

15

However, Obama not only refused to acknowledge the government’s role in the collapse, but he took credit for rescuing the dastardly banks from it: “We took difficult and, frankly, unpopular steps to pull them back from the brink, steps that were necessary not just to save our financial system, but to save our economy as a whole.”

With that predicate, he told bankers they owed it to the country to help lift the economy out of crisis. He leaned on them to show their gratitude for his magnanimity by making loans he wanted them to make, as opposed to those consistent with managing risk properly. In other words, he pressured them to do more of the very kind of politicized, irresponsible lending for which he was condemning them. Obama said, “So my main message . . . was very simple: that America’s banks received extraordinary assistance from American taxpayers to rebuild their industry, and now that they’re back on their feet we expect an extraordinary commitment from them to help rebuild our economy.”

“We expect?” The Central Planner in Chief concluded, “That starts with finding ways to help credit-worthy small and medium-size businesses get the loans that they need to open their doors, grow their operations and create new jobs.”

16

The next week Obama met with CEOs and other officers of a dozen community banks to pressure them to increase their small-business lending and lobby them to support his regulatory overhaul plans.

17

Obama continued the executive branch assault on the banks into 2010. In January he unveiled a proposal for a Financial Crisis Responsibility Fee—a euphemism for a bank penalty tax, a version of which he had first suggested months before. The tax would apply to the nation’s largest financial institutions (banks, thrifts, and insurance companies with more than $50 billion in assets) for the ostensible purpose of “recover[ing] every single dime the American people are owed” for bailing out the economy. Obama said it would remain in effect until the TARP losses, estimated at $117 billion, were recovered, in ten or twelve years. As if working in tandem with Obama, a number of congressional Democrats proposed a 50 percent tax on bonuses above $50,000 at banks that received bailout money.

After Obama announced his tax proposal, even the

New York Times

admitted he “spoke in some of his harshest language to date about the resurgent financial industry.” Obama said, “My determination to achieve this goal is only heightened when I see reports of massive profits and obscene bonuses at the very firms who owe their continued existence to the American people—who have not been made whole, and who continue to face real hardship in this recession.”

18

He further claimed,

We’re already hearing a hue and cry from Wall Street suggesting that this proposed fee is not only unwelcome but unfair. That by some twisted logic it is more appropriate for the American people to bear the cost of the bailout rather than the industry that benefited from it, even though these executives are out there giving themselves huge bonuses. What I say to these executives is this: Instead of sending a phalanx of lobbyists to fight this proposal or employing an army of lawyers and accountants to help evade the fee, I suggest you might want to consider simply meeting your responsibilities.

19

It couldn’t have been more disingenuous for Obama to frame this retroactive penalty as an effort to “recover” money “owed” to Americans, when most of the affected banks had already repaid their bailout debts with interest. When the banks protested, the White House responded that the measure was aimed at the institutions whose risk-taking had caused the financial crisis, which was tantamount to an admission that it was, in fact, a retroactive penalty.

20

It was also dishonest for Obama to call his tax a “fee.” As the Heritage Foundation’s Retirement Security and Financial Markets guru David C. John said, the “responsibility fee” is neither responsible nor a fee. However, “The White House needs a villain to blame for the nation’s continuing economic woes, and Treasury desperately needs revenues to reduce the massive deficits caused by the Obama administration’s spending policies.” A more candid explanation of the targets of the “fee,” suggested John, would mirror Willie Sutton’s answer to why he robbed banks: “Because that’s where the money is.”

21

Obama didn’t cotton to backtalk from the banks, slamming them again in his weekly radio address. “Like clockwork, the banks and politicians who curry their favor are already trying to stop this fee from going into effect. We’re not going to let Wall Street take the money and run. We’re going to pass this fee into law. . . . If the big financial firms can afford massive bonuses, they can afford to pay back the American people. Those who oppose this fee have also had the audacity to suggest that it is somehow unfair. The very same firms reaping billions of dollars in profits, and reportedly handing out more money in bonuses and compensation than ever before in history, are now pleading poverty. It’s a sight to see.”

22

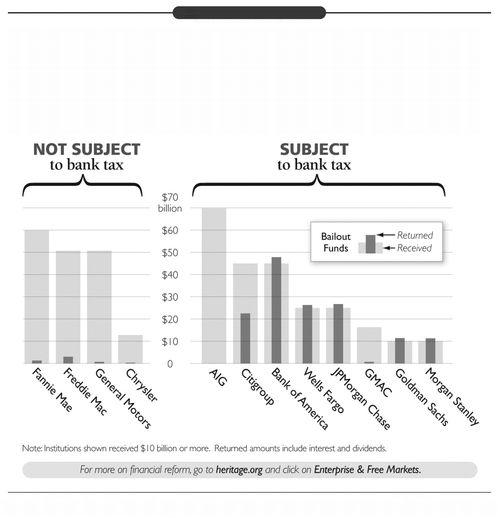

With Obama’s proposed tax, we saw, once again, that he was trying to pick the winners and losers, taxing some banks that had paid their debts in full, with interest, and exempting government-connected ones such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, GM, and Chrysler, that still owed billions. Heritage Foundation expert on government regulation James Gattuso observed that while Obama claimed his new tax would “pay back the taxpayers who rescued them in their time of need . . . in truth, the new tax would do nothing of the kind. Mr. Obama knows that almost every major bank has paid back their bailout funds, with interest. Taxpayers made substantial profits on those repayments.” Heritage presented a chart, reprinted below, to illustrate Gattuso’s point that many banks that paid their debt would be taxed, and many who didn’t would be exempted.

23

Source:

PmPublica. at

http://bailoutpropublica.org/main/list/index

. The Heritage Foundation

This bank “fee” is manifestly unfair and ill-advised for other reasons as well. It would be imposed irrespective of whether a bank was profitable. Furthermore, the fee would come on top of other new proposed fees on the same institutions and of corporate income taxes they pay. Nor was the fee structured to deter further irresponsible risk taking. And, of course, who can possibly believe the White House’s claim that the fee would sunset after TARP deficits are eliminated a decade from now?

24

“TARP ON STEROIDS”

Obama’s proposed bank tax was eventually rolled into a sweeping plan, unveiled in June 2009, to overhaul the financial system. Treasury secretary Tim Geithner—in keeping with the administration’s philosophy that Alinksyites should never let a crisis go to waste—emphasized that the banking system “was fundamentally too fragile and unstable and it did a bad job of protecting consumers and investors.... The damage of the crisis was just too acute. We are trying to move very, very quickly while the memory of the crisis is still in the forefront of people’s memory.”

It was a stunningly candid admission. Furthermore, as a good central planner, Geithner complained that America’s financial system is much less centralized than other “mature” economies, and that we need a more centralized regulatory system to make this vast system accountable. The proposed bill would give a new council of regulators the authority to identify and monitor large financial firms (those “too big to fail”) that were in trouble, seize control of them, and wind them down to avoid their collapse, a scenario Geithner claimed would be limited to “extraordinary circumstances.”

25

The plan contemplated covering the costs of such dissolutions by imposing a “fee” on firms with assets of $10 billion or more .

26