Criminal Minds (24 page)

Authors: Jeff Mariotte

A new serial killer had earned her fascination, and she began corresponding with him: Sunset Strip Murderer Doug Clark, formerly romantically linked to Carol Bundy. Compton soon took Bundy’s place in Clark’s heart, and the two shared an intense romance through the U.S. mail. As a valentine, Clark sent Compton a photo of himself posed with a headless female corpse. Romance flared in Compton’s heart, and she wrote to him, “I take out my straight razor and with one quick stroke I slit the veins in the crook of your arm. Your blood spurts out and spits atop my swelled breasts. Then later that night we cuddle in each other’s arms before the fireplace and dress each others wounds with kisses and loving caresses.”

Compton escaped from prison in 1988, but was recaptured. She was finally released in 2003. After her release, she married a college professor she had met and seduced in prison. She wrote and self-published a book in 2002 called

Eating the Ashes

, about her experiences in the penal system.

Eating the Ashes

, about her experiences in the penal system.

9

The Helpless Ones

AS HEINOUS AS THE ABDUCTIONS

, rapes, and murders of adults are, there’s something particularly chilling when the same crimes are committed against children, the most helpless among us. A man or a woman who is victimized at least has a fighting chance of surviving and, having survived, of overcoming the mental and emotional trauma. But a child victim, even if he or she survives, faces an entire life scarred by the experience.

, rapes, and murders of adults are, there’s something particularly chilling when the same crimes are committed against children, the most helpless among us. A man or a woman who is victimized at least has a fighting chance of surviving and, having survived, of overcoming the mental and emotional trauma. But a child victim, even if he or she survives, faces an entire life scarred by the experience.

On

Criminal Minds

, as in real life, children can be both victims and perpetrators of crimes. In the episode “What Fresh Hell?” (112), eleven-year-old Billie Copeland is the victim of stranger abduction, and this serves as the focal point for a discussion of various child victims.

Criminal Minds

, as in real life, children can be both victims and perpetrators of crimes. In the episode “What Fresh Hell?” (112), eleven-year-old Billie Copeland is the victim of stranger abduction, and this serves as the focal point for a discussion of various child victims.

ONE OF THE CHILDREN

ONE OF THE CHILDRENmentioned in “What Fresh Hell?” is Polly Hannah Klaas, who is also referred to in the episode “Seven Seconds” (305). Twelve-year-old Polly was having a slumber party on October 1, 1993, when a man entered her bedroom with a knife. Insisting that he was “just doing this for the money,” he tied up the three girls, put pillowcases over their heads, and left with Polly. One of the girls freed herself and woke Polly’s mother, Eve Nichol. Nichol was separated from her second husband at the time, and she and Polly lived with Polly’s half-sister in Petaluma, California. Nichol dialed 911 immediately, kicking off a search that would include terrible missteps.

Although Polly’s father, Marc Klaas, was an immediate suspect, the story the girls told seemed to eliminate him, since Polly would certainly have recognized him. The Petaluma police broadcast a description of Polly’s abductor, but not every police officer in the area received the report.

Responding to a trespassing report near Santa Rosa, twenty-five miles away, the sheriff’s deputies encountered a man standing by a Ford Pinto stuck off the road. He was sweating profusely, despite the late hour and the cool night. The police checked for outstanding warrants, and the man came up clean. However, a full background check would have shown that he was wanted for violating parole on a previous crime and that he had a long history of violent assaults against women and girls, along with robbery, burglary, and kidnapping. That would have allowed them to search his car, which might have saved Polly’s life. Instead, the police freed the stuck Pinto and let Richard Allen Davis drive away.

Within days, the details of Polly’s abduction and her abductor were everywhere: printed on posters, spread through computer networks, faxed around the country, and shown on

America’s Most Wanted

. Actress Winona Ryder, who grew up in Petaluma, offered a reward of two hundred thousand dollars. The Polly Klaas Center was established to coordinate the efforts and accept telephone tips. Nichol and Klaas were definitively ruled out as suspects through polygraph tests.

America’s Most Wanted

. Actress Winona Ryder, who grew up in Petaluma, offered a reward of two hundred thousand dollars. The Polly Klaas Center was established to coordinate the efforts and accept telephone tips. Nichol and Klaas were definitively ruled out as suspects through polygraph tests.

On October 19, Davis was picked up for drunk driving. The arresting officers didn’t note his resemblance to the sketches of Polly’s abductor that had been so widely circulated, and he was released once again.

The Polly Klaas Foundation achieved tax-exempt status, and Bill Rhodes, the print-shop owner who had started it, was named its president. Although the hunt for Polly was still on, the foundation expanded its mission to the search for missing children everywhere. Rhodes turned out to be a registered sex offender who had preyed on young girls, using a knife to subdue them. He then became an instant suspect, since the perpetrators of such crimes often like to involve themselves in the investigations. The police checked out his alibi and cleared him, but he was removed from the foundation.

On November 28, the owner of the rural land on which Davis had been trespassing when his Pinto got stuck found some strange items on the property, including a sweatshirt, red tights, a condom wrapper and a loose condom, and binding tape. Police looked at the old trespassing complaint and finally matched Davis with a palm print found in Polly’s room. They picked Davis up, and after a few days in custody he confessed to Polly’s murder, then led the investigators to where her body had been exposed to the elements for the last two months. He had strangled her with a piece of cloth after the run-in with sheriff’s deputies over the stuck Pinto. He denied having molested her, but his story was full ofinconsistencies, and there was no scientific way to tell after so much time had passed.

Davis, a loser who had spent his life in and out of prison, was convicted of first-degree murder with special circumstances. His reaction to the verdict was to display both middle fingers to the courtroom. When he was allowed to speak at his sentencing hearing, he used the opportunity to claim that Polly told him that her father had sexually molested her. The judge said that this outburst made it very easy to sentence Davis to death, which he did. As of this writing, although the California Supreme Court recently upheld the sentence, Davis remains on death row at San Quentin.

Marc Klaas (who later created the group KlaasKids) and the original Polly Klaas Foundation have become tireless advocates for missing children and have helped many families reunite.

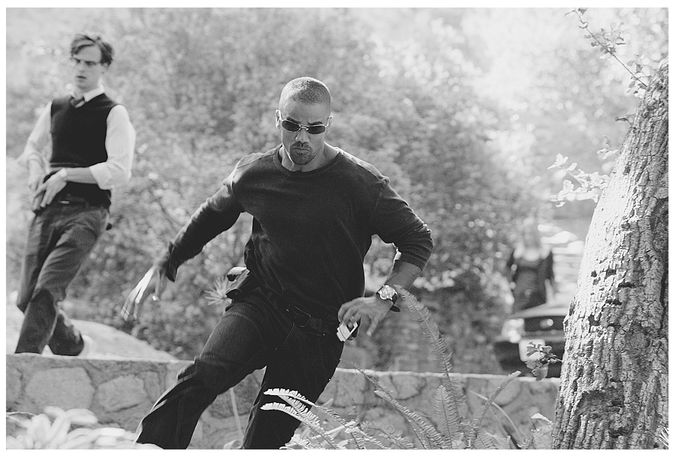

In “The Boogeyman,” Dr. Reid and Morgan examine a tight-knit community in Texas to determine who has been victimizing local children.

ANOTHER YOUNG

ANOTHER YOUNGvictim mentioned in the episodes “What Fresh Hell?” (112) and “Seven Seconds” (305) is Danielle Van Dam. Danielle was seven years old on February 1, 2002, when she was taken from her home in the upscale San Diego suburb of Sabre Springs. Her mother, Brenda, had gone out to a bar with friends, leaving her father, Damon, at home with the girl and her two brothers. Damon put Danielle to bed around 10:30 p.m. When Brenda returned home at 2 a.m. with her friends, she shut Danielle’s door but didn’t look in on her. The friends stayed for about an hour, then left. In the morning, Danielle was gone. Her parents searched the house, growing increasingly frantic, then called the police.

The case quickly turned into a media sensation—it was a Polly Klaas-style disappearance, but in an age even more saturated with twenty-four-hour news channels and the Internet. Brenda and Damon held news conferences and appeared on national TV shows like

Today

and

Larry King Live

, expressing their hopes that their daughter’s abductor would bring her home safely.

Today

and

Larry King Live

, expressing their hopes that their daughter’s abductor would bring her home safely.

It didn’t take long for the Van Dams ’ personal lives to be made an issue in the case: they were swingers and were open about their lifestyle. Brenda was bisexual, and she had watched her husband having sex with her friends. While their private lives didn’t seem to make a difference, when a suspect was arrested and the case finally brought to court, these factors were raised as a way to claim that the accused wasn’t the only person with access to Danielle; the friends—two women and two men with whom Brenda had been out drinking and dancing—might have done something to the girl.

In the end, that was all a distraction. One of the people in the bar that night was David Westerfield, a neighbor who lived two doors down from the Van Dams. Westerfield drove his RV out into the California desert that weekend, and a tow truck operator reported having towed it from deep sand near the Mexican border. When Westerfield returned home with his RV, he had it thoroughly cleaned. He also dropped off laundry at a dry cleaning shop that weekend: comforters, pillowcases, and a jacket. Testing would later reveal Danielle’s blood on the jacket as well as inside the RV. The police rapidly made Westerfield a suspect and put him under surveillance. They found child pornography in his home, but it was the DNA evidence from the jacket and the RV that led them to place him under arrest. He denied abducting Danielle, and he had no criminal record.

Five days later, on February 27, Danielle’s body was found in a remote desert spot, twenty-five miles from San Diego. She had been dumped almost immediately after her disappearance, with no attempt made to cover her up. The authorities were unable to determine the cause of death because her body was badly decomposed.

At his trial, Westerfield, who had failed a polygraph test, continued to proclaim his innocence. In addition to offering the DNA and fiber evidence and the massive amounts of pornography found in his home, the prosecution showed that Westerfield had fondled his own niece when she was seven years old. (In an echo of this case, the victim in “Seven Seconds,” six-year-old Katie Jacobs, is abducted from a shopping mall by her uncle, who has been molesting her.)

The jury convicted Westerfield of kidnapping and murder, and he was sentenced to death. After the trial was over, a rumor spread that he had been about to make a deal for life in prison in return for showing the location of Danielle’s body, but just before the details were hammered home, her body was located. Like Richard Allen Davis, Westerfield is currently awaiting execution at San Quentin.

DR. SPENCER REID

DR. SPENCER REIDlooks into an old case that stimulates dreams about half-recalled memories of his own childhood, in the two-part “The Instincts” (406) and “Memoriam” (407). When Reid was a boy, he had known the victim, six-year-old Riley Jenkins, and the mystery’s solution reaches deep into Reid’s own life, helping to explain his parents’ divorce.

Other books

The Dragon Queens (The Mystique Trilogy) by Traci Harding

The Exposure by Tara Sue Me

More Than Lies by N. E. Henderson

Lost Memories (Honky Tonk Hearts) by Thomas, Sherri

Whiplash by Yvie Towers

The Shroud of A'Ranka (Brimstone Network Trilogy) by Thomas E. Sniegoski

Cornbread & Caviar by Empress Lablaque

Operation Sea Ghost by Mack Maloney

The King's Diamond by Will Whitaker

Through Lies and Heartache by WB Amore