Critical thinking for Students (4 page)

Read Critical thinking for Students Online

Authors: Roy van den Brink-Budgen

We’re beginning to see how arguments are built up, piece by piece, claim by claim. It is probably a good time to introduce a refinement to the terms used in describing what’s going on in arguments.

We have seen that the basic feature of an argument is that of a line of inference. A claim is inferred from another one. To distinguish which claims are doing what, we refer to them as either ‘reasons’ or ‘conclusions’. The idea of a ‘reason’ should fit with how we’ve been looking at inference. You’ll remember this example that we looked at a little earlier:

It is good that so many young people, both boys and girls, hug each other, because the need for people to hug each other in today’s world is understandable.

The word ‘because’ tells us that the second half of the sentence is the reason used to draw the inference in the first half. So we can see that is what’s going on in the most basic type of argument:

Claim (= reason) → claim

There’s also a term that’s used for the claim that’s an inference. This is ‘conclusion’. This term is appropriate because it’s where the argument has ended up. It’s the final destination. It’s where the author of the argument wants to go.

The use of sunbeds to get a tan should be banned. More than 10,000 people a year in the UK are developing malignant melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, with sunbeds being one of the main causes.

If we look again at this argument, though we saw that the inference was the first sentence, it was where the author wanted to go. It was the point that they wanted to make. In this way, then, the first sentence was what would be called the ‘conclusion’ of the argument. You might come across all sorts of ways of seeing this explained, but the simplest (and thus most effective) way of seeing what a conclusion is is to see it as the main point that the author wants to make. In the above example, you can see that the author’s main point is to say that sunbeds should be banned. The evidence on skin cancer and the link between it and sunbeds are claims which help the author on their way.

Look at the next example. It should be pretty clear what’s going on:

Parents need to control how their children use their mobile phones. Evidence has shown a recent doubling in the texts received and sent by teenagers, with an average of about 80 messages a day.

All we have is two claims, with the second one providing a reason for the first one. As you can see, the main point the author wants to make is the first sentence: this is the conclusion drawn from the evidence.

Before we move on, you will see that we’re still very much looking at the significance of claims. The evidence-claim (second sentence) is given a significance by the author when the inference is drawn. Without this inference, the claim simply sits there with no necessary significance. When we come to look at assumptions in arguments, we’ll be very much into this again.

Anyway, back to the short argument. We can show what’s going on by labelling the passage.

(C) Parents need to control how their children use their mobile phones. (R) Evidence has shown a recent doubling in the texts received and sent by teenagers, with an average of about 80 messages a day.

Though the sequence in the argument is C ← R, we’d normally show the process of inference as R → C.

We’ll now add to this argument.

Parents need to control how their children use their mobile phones. Evidence has shown a recent doubling in the texts received and sent by teenagers, with an average of about 80 messages a day. In many cases, teenagers are sending and receiving messages through the night, causing them to lose sleep.

We now have another evidence-claim. What is this doing? It’s providing, in the third sentence, another reason for the conclusion. The author is arguing that the big increase in numbers of texts sent and received is the first reason for parents to control their children’s use of phones. The effect on their children’s sleep is the second. So we now have R + R → C. This is often shown as a vertical sequence.

There is a technical point that we can deal with here. We have given the structure of the argument as R + R → C (or in its other vertical form). But there is another way of showing this, which says something about the reasons themselves.

In this example, the reasons are what are called ‘independent’. This means that they work separately, each one supporting the conclusion from a particular direction. A simple test to see how this works is to look at what would happen if a reason was removed. If it is an independent reason, the conclusion could still be drawn. We know that, in our example, the second reason could be taken out because we’ve already seen the conclusion drawn with just the first one. So what happens if we take out the first one?

Parents need to control how their children use their mobile phones. In many cases, teenagers are sending and receiving messages through the night, causing them to lose sleep.

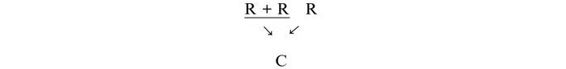

As you can see, it still works. So the reasons operate independently. We can show this independent reasoning in a particular way.

In this version, the lack of the + sign indicates that the conclusion doesn’t need the two reasons added together. In addition, the way that the reasons do their work is shown by each reason having its own arrow, rather than one for both of them.

In the next example, we again have a conclusion drawn from two reasons.

(R) Teenagers have a great interest in knowing what’s going on in the lives of their peers. (R) They will be very anxious if they’re left out of the loop. (C) So the big increase in texting can be seen as both positive and negative.

You will be able to see that, in this argument, the conclusion needs both reasons. Just try it with only any one of them. You’ll see that the first reason needs the second to arrive at an inference which sees texting as both negative and positive. The second reason highlights only a potentially negative aspect.

So here we don’t have independent reasons. We have what are called ‘joint’ reasons. They work together. We show this working together by using the + sign.

It can also be shown with the reasons connected in the following way.

Can we have arguments with a mixture of joint and independent reasons? Yes, we can.

Teenagers are supposed to increasingly break free from their parents during adolescence. Texting enables the teenager to keep in touch with their parents, about the smallest detail of their lives. Teenagers need peace and quiet in their lives to develop into the person they want to be. So the big increase in texting can be seen as restricting the psychological development of teenagers.

What’s going on in this argument? We’ve got two lines of reasoning. The first two sentences work together to show one negative aspect of texting for the psychological development of teenagers. The third sentence comes in with a separate line of reasoning to show another negative aspect. The argument therefore combines both joint and independent reasons. We can show it in the following way.

Just to make sure that we’ve got this right, just try the argument by removing reasons. If we remove the third reason, what do we have?

Teenagers are supposed to increasingly break free from their parents during adolescence. Texting enables the teenager to keep in touch with their parents, about the smallest detail of their lives. So the big increase in texting can be seen as restricting the psychological development of teenagers.

As you can see, the argument still works: the conclusion can still be drawn.

But what happens if we remove the first sentence?

Texting enables the teenager to keep in touch with their parents, about the smallest detail of their lives. Teenagers need peace and quiet in their lives to develop into the person they want to be. So the big increase in texting can be seen as restricting the psychological development of teenagers.