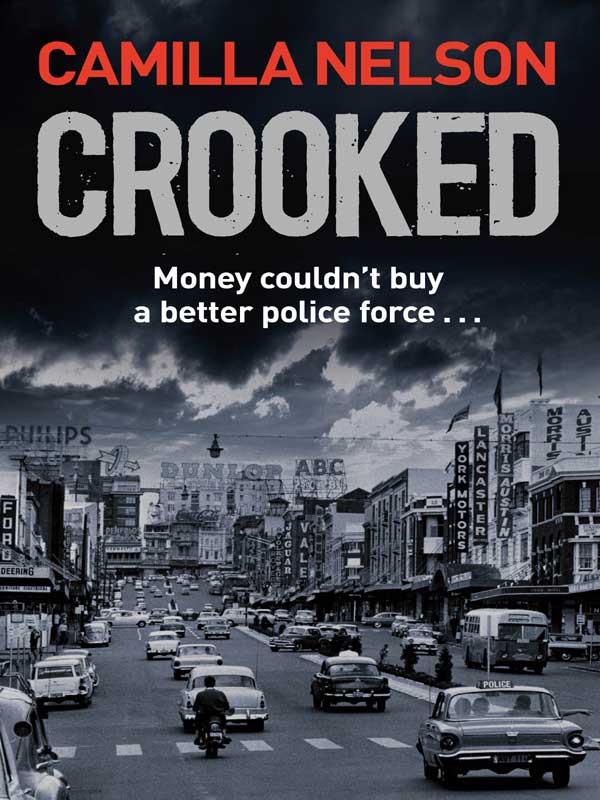

Crooked

Camilla Nelson was born in Wollongong and grew up in Sydney. Her first novel,

Perverse Acts

, was published in 1999 and she was named one of the

Sydney Morning Herald

's Best Young Australian Novelists of the Year. Camilla worked for a minister in the NSW State Government before turning to journalism. She has an MA in History and a Doctorate of Creative Arts. She currently lectures in Writing and Cultural Studies at the University of Technology, Sydney.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Crooked

ePub ISBN 9781742745220

Crooked

, though based on and inspired by historical events and real people, is a work of fiction.

A Bantam book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First published by Bantam in 2008

Copyright © Camilla Nelson 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the

Australian Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Nelson, Camilla

Crooked.

ISBN 978 1 86325 605 6 (pbk.).

A823.3

Cover photo by Getty Images

Cover design by Blue Cork

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

This book was written with the assistance of a Varuna Fellowship.

For my father

Frankly, I do not think the right people were arrested.

Hansard

, 1968

J

ANUARY

1968

This was the moment Gus had been coming to ever since the start. He was acutely aware of the water trickling from the holding tank into the stainless steel urinal, the way the light glinted on the splashbacks and scratched metal basins, the naked bulb burning in the hallway outside. He sensed the approach before he saw him in the mirror. He experienced the moment at one remove, as if it was happening to somebody else.

âIt's you,' said Gus. âIt's been you all along.'

âI never doubted your intelligence. I'd hoped your courage wouldn't fail when it came to the point.'

âI trusted you.'

âAnd I'm grateful for that. So tell me you're okay, and we'll forget all about this.'

Part of Gus wondered if there might still be a way to turn things around â to make everything right, like they did in the movies.

âI can't ⦠You're a crook.'

âYou've got no proof, no real evidence.'

There was plenty of light for Gus to see him remove the gun from his pocket, and take off the catch.

âIs that how you fix things?'

âBelieve me, I don't want to do this.'

âToo bad.'

The next thing Gus heard was the sound of the metal hammer striking the firing pin. The explosion echoed off the walls. His arms went up, his eyes squeezed tight. He felt himself falling through a world of pain.

Charlie Gillespie blinked down at the grubby paper packet on his desk, touching it gingerly with the tip of one finger, as one might approach the set mechanism of a mouse trap. His office was located on the third floor of a dilapidated five-storey walk-up and looked more like a garbage room than a legal practice. The room was narrow and awkward, lit indirectly from a slat glass window that glanced down through the light well of the building. The meagre furnishings comprised a desk of wood-grained plastic laminate on a pink metal base, a Dunlopillo convertible day-and-night couch in dead-lettuce green and a large chromium ashtray on a pedestal that was blossoming with fag ends. Through the glass louvres of the window, three of which were cracked and in need of replacement, wafted the smell of detritus and the city.

He had heard rumours that it was possible to square things, to win cases that might not otherwise seem winnable. He himself had been at the Sydney Quarter Sessions when the performance of well-known prosecutors became suddenly lacklustre, when police witnesses turned tail in a manner that was almost ridiculous, and defence lawyers seemed, as if by a strange magic, to anticipate and waylay the prosecution case. He prodded the packet again with his finger, and traced its circumference on the blotter of his desk. Suddenly he felt threatened. He would return the thing immediately. He would meet Reg Tanner at the

Latin Quarter nightclub, but tell him flat out there was nothing to be done. He would not be abrasive. He would apologise profusely. He would say he was wrong, that he had mistaken the matter entirely.

Charlie paused on the threshold, then stepped out into a billowing autumn afternoon. He gazed mournfully and not a little thirstily at the shut doors of the Hotel Australia, turned his face against the arrhythmic westerly wind as it swept the dust and street litter up into spirals, and threatened to turn the pedestrians of King Street into a tailspin. He had to think. Think! He mounted the rise as the last shaft of sunlight tickled the verdigris spire of St James, the old almond-coloured church that floated over the rise where King Street met the upper portion of Phillip at the Queens Square Courts. Two barristers and a moon-faced legal clerk were trotting up the hill in front of him, their wigs set rakishly askew, their robes like giant magpie wings flapping in the slipstream.

He struck the bottom end of Phillip Street then set out through the soot-riddled arcades under Cahill's Expressway at Circular Quay. He walked through the shudder of traffic and the roar of an electrical train overhead, and breathed in the dank fishy smell squalling in off the Harbour. He was sweating profusely and his forehead was puckered where his hat was too tight. Puffing a little, he leaned with his back to the spiked iron railings edging the Quay, staring up through a tangle of electrical wires at the girl in a white swimsuit smiling down from a billboard. âYes ⦠You Can Take Vincent's Headache Powders with Confidence'. Under the billboard, a bunch of old winos gathered in a tangle of blue shadow, stuck out their grimy hands, and asked for ten bob to keep going.

Charlie purchased a paper from a cloth-capped street seller, before striding in through the pub doors. He downed three

schooners and a plate of steak, eggs and chips, telephoned his wife to say he'd be late and, at nine o'clock precisely, threw back his shoulders, clenched his fists, and turned his feet in the direction of the polite orange glow on Pitt Street that was Sammy Lee's Latin Quarter.

Charlie walked under the candy-striped awning and through the rotating glass doors. He'd been to the Latin Quarter many times, but the place never ceased to astonish him. It was a shimmering grotto of tropical blossoms, floor-to-ceiling mirrors and quilted satin doors, with a scattering of tables either side of a pocket-handkerchief dance floor. On a dais at one end, a tuxedoed orchestra played a prettied up rumba, while dancers in brassieres and feathers plucked at the air with jewel-spattered fingers and whirled and fandangoed under green and orange lights.

âCharlie, my mate. How are you?'

Charlie brushed aside a palm frond in three blushing shades of tropical lime, and sat facing Reg Tanner at a table in the corner.

âCharlie, you remember my mate, Pigeye?'

Charlie didn't, but he grinned and stretched out a hand. Pigeye grinned back at him, and reached forward and shook it without rising.

Tanner snapped his fingers in the air, and within minutes the table was groaning under an assortment of beer jugs and glasses, capon-stuffed olives, devils-on-horseback and dishes of nuts. Charlie had seen Tanner around the courthouse, but realised that he had never really examined him properly. He was a thickset, barrel-chested man in his fifties, with flat, squarish muscles. He had a crop of grey hair flying back from his forehead, eyelids that hung down in thick, overlapping folds, and a grin that never left his face, although he looked ready to break the room apart.

He made Charlie feel nervous.

âTwiggy's delivered the package?' said Tanner.

Charlie inclined his head.

âGood. I was starting to think she was getting unreliable. It's the drugs, I reckon. They addle her head.'

Charlie thought about the girl with the look of an indigent starveling who'd walked into his office that afternoon. The drugs explained a lot. âThe money's to help out with the O'Conner case?'

âIn a manner of speaking.'

Pigeye interjected. âSee, we heard he doesn't like it in D Block at Pentridge, and we thought we could help you do something about it.'

Charlie thought he understood which way things were heading, but wasn't sure of his ground. âYou're telling me you would be willing to, you know ⦠put in a good word?'

âIt'd take more than a word to get a smart bastard like O'Connor out of gaol. Bloody hell,' said Tanner, laughing.

âThey haven't got any evidence worth a damn,' replied Charlie, but this only caused Tanner to break into fresh gales of laughter.

Pigeye managed to look hurt. âCome on, Charlie. For the amount you'll be getting, I reckon you ought to be grateful.' He glanced away, his orange-freckled skin drawing back tightly over his flesh. He drank off the rest of his beer and sank into himself.

Tanner drew out the silence for several seconds, during which Charlie was assailed by fresh doubts. âExactly what is it you want me to do?'

Eventually Tanner shifted his weight and said, âI've been speaking to some coppers down in Melbourne. I can tell you they're slack-arse bastards down there, and generally don't do too much business, but this bloke â¦' he scrawled something down on a napkin and pushed it across the table. âWe've done a bit of business with him, no questions asked. I've spoken to him about them running crooked at the hearing, and he tells me

they'll cop it. But you've got to make it good for them. Sweeten them up.'

âWhy me?'

âYou're his lawyer.'

Charlie took a deep swallow of his beer and blundered straight on. âChrist. It sounds a bit risky.'

âTrust me, Charlie. Just take the money and give it to the bloke, that's all we're asking. I can guarantee that there aren't going to be any problems. I'd do it myself but it would look a bit odd.' Tanner paused, then added, âThis matter sorts itself out right, I reckon there'll be more I can give you in a similar line.'

Charlie knew that if he was going to say no, he'd have to say it now, and say it very firmly, but it seemed the matter had already progressed too far. Just as he made his mind up to say it anyway, the air swelled with wild phrases of music from the bandstand. The horn player was on his feet, blatting and wailing. Then the alto was up, and the singer was kissing him and climbing down off the stage. She swayed through the tables, dressed like a giant sea creature in a swathe of green spangles.

Tanner got up. âDolly Brennan,' he said, holding her out at arm's length. âWell, look at you.'

Dolly lifted her face, tilting it somewhat to the side.

âJust like Venus on her cockleshell,' said Tanner, and planted a thick kiss on her cheek.

âWhy, Mr Tanner! How you do carry on!' Dolly flicked him on the shoulder, before hitching her train and sitting herself down with an easy sort of preening motion. âOh dear, am I butting in on something?'

âNever,' said Tanner. âI reckon these blokes are just stunned like a row of mullets on account of what a great little gargler you are.'

Dolly laughed a shrill, artificial laugh, and angled her head towards Charlie. âWho's this?'

Tanner also turned to look at him, as if questioning his presence. âThis bloke? He's a lawyer.'

Charlie fancied he'd seen Dolly somewhere before, most likely in the courthouse on the wrong side of the dock.

âWhat?' Dolly shrieked. Fresh gusts of laughter blew about the table. âOh, my God! But he hasn't got his wig on.'

âNot all lawyers wear wigs,' said Tanner, patting Dolly's hand.

Dolly slapped him on the wrist. âGo on, Mr Tanner! I was just having a lend of the bloke.'

For some reason this was thought to be unbearably funny. Tanner and Dolly fell over each other, laughing.

âOh, my God!' Dolly jerked herself upright. âHere I am and I clean forgot the reason I came butting my fat head in.' She cupped a hand to her mouth and whispered a few words into Tanner's ear. Tanner, growing suddenly serious, got up and excused himself â and Pigeye followed suit, drifting off into the eddy and swirl of the crowd, with the frayed ends of Dolly's laughter wafting behind them.

Charlie stayed at the table after the others departed and consulted his conscience. It had been kicking and goading him all afternoon, but now it was silent. There weren't any butterflies, stomach pains, or feelings that his insides were dropping out. He was feeling weirdly euphoric, as if he was pumped up with gas and might float into space.

âLooks like you badly need a drink.'

Sammy Lee, the manager and proprietor of the surrounding extravagance, was standing, bottle in hand, at his elbow. Sammy was a thick-bodied, olive-skinned man in his mid-forties, with a shock of dark hair comically kinked off to one side. He had once been bright-faced, baby-cheeked and full of enthusiasm, before success took its toll and a series of shady-looking characters (split ears, mutilated thumbs) decided to join him as

a 50/50 partner. In the tawdry club-light, his face looked yellow and pendulous, his soft, dog-like eyes leaky with liquid, and a cloud of deep gloom gathered over his head.

Charlie's first encounter with Sammy had been about changing his name from Samuel Levi by deed poll.

âNo worries, Charlie. I didn't hear anything. But with those particular coppers at the centre of it â'

âWell, you don't have to worry. There's nothing between that lot and me except a legal matter in need of attention.'

âI guess that's all right then,' said Sammy, sounding doubtful. He poured them both a drink, then cast his eyes around the room, before leaning into the table. âJust look who they're with.'

Charlie followed the line of Sammy's gaze to the far end of the room, where Tanner was drinking. Seated beside him was a large-limbed man of some forty-odd in a lairy-looking shirt and dark blazer. He had an elongated brown face, and eyes that stared out obliquely through half-veiled lids, as though they were peering through a peephole. Charlie didn't know him, but the bloke was returning his look with several long horse-like nods of acknowledgement.