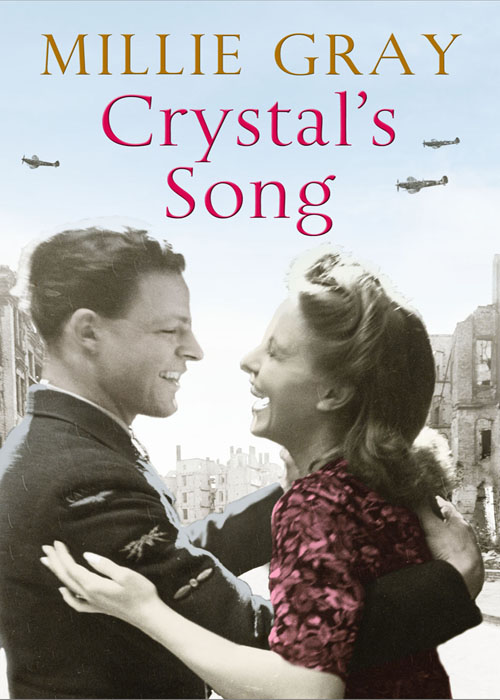

Crystal's Song

Authors: Millie Gray

Dedicated to Celia Baird

The author’s thanks go to:

Gordon Booth for his editing and advice;

Martha Booth for her encouragement and support;

and for sharing their memories of a Leith childhood and a

Leith long gone, my grateful thanks to my sisters Mary

and Margaret and my friend Celia.

PART ONE

1

“You’ve got lots to do, Senga. You really need to get a move on!” urged Phyllis.

Senga shivered as she began pulling a jumper over the summer dress she was wearing. “I know, but I’m that feart, so I am.”

“Feart of going out in the snaw?” replied Phyllis as she tried unsuccessfully to raise herself up.

Wincing, Senga picked up a towel and neatly rolled it up before lifting her paralysed sister’s head and gently placing the towel under the pillow.

“That feel any better?” she asked pleadingly. But when Phyllis nodded and smiled, the gesture only served to make Senga feel worse. She’d felt so badly now about having blamed everyone for her having rickets as an infant. These rickets, unfortunately, had resulted in her left leg bending outwards. Bandy-legged they called her now but nevertheless her bandy leg worked. Then beautiful Phyllis had been struck down by polio two years ago. Senga’s sense of guilt had deepened even more when Phyllis returned from hospital and it became evident that she would never be able to move freely. She’d never run a message, never skip, nor ever play peevers again. Only nine years old she’d been then – and Senga had heard all those whispers that her elder sister wouldn’t … But Senga refused to let her mind dwell on these sad predictions – after all, people had once said she herself would never walk, yet now she did.

“Naw, I’m no feart o’ the snaw. It’s that bloomin’ attendance officer coming here the day that’s giein me the heebie-jeebies.”

Phyllis chuckled. “Look, Senga, it’ll be okay. He’ll no expect to see you this week after me telling him you’d been smitten with the bubonic plague.”

“If only I had been, life would be a lot easier.”

“You think so?”

“Aye, ’cause I’d hae been bricked in where he couldnae get at me and tak me aff tae the bad lassies’ school.” Senga became wistful. “Wish we were still living across the lobby frae Granny Kelly.”

The two sisters fell silent. Both were remembering how it was Phyllis catching polio that had got them out of the slums of West Cromwell Street. Aye, the authorities were adamant that they wouldn’t allow Phyllis home from hospital until there was a guarantee of satisfactory sanitary conditions. And in no way did the family’s rat-ridden and bug-infested single-end in condemned West Cromwell Street meet the minimum of those standards – especially when it was noted that they only had a cold water tap and access to a communal lavatory which they had to share with forty other people.

Yet, if she was being truthful, Senga would have to admit she did so like staying in Restalrig Circus, where every house had three rooms, a large kitchen and a bathroom. It was a whole world away from West Cromwell Street. Most of all she loved the garden and before her father had been called up, he’d kept it all so nice, planting vegetables, fruit and flowers. But Mum … well, Mum was just Mum. Senga grinned, thinking that now the ground was covered by four inches of snow her garden looked so beautiful again and no different from anyone else’s!

A loud drumming on the outside door alerted the girls.

“Quick!” whispered Phyllis. “Hide under my bed.”

The bed in question was a long, topless, coffin-shaped wooden structure on wheels. The wheels had been fitted to make it easier to move around the house – and even outside into the fresh air – but to be truthful, since Tam their father had left, it was still too cumbersome for slightly built Senga and Johnny, her strapping but gangling ten-year-old brother, to manoeuvre easily.

Senga had just squeezed herself under the bed when the rapping stopped, the door opened, and a voice called out, “It’s no the rent man. It’s only me.”

“Oh, it’s just you, is it, Etta?”

“Less o’ the

just

,” teased Etta, squinting at the bed. “You lost something, Senga?” she went on, as she expertly fished Senga out of her hiding place.

“Naw. I thought you were … well, you surely ken I’m on the run.”

Etta smiled. This dramatic retort was what she expected from Senga, whom she judged to be the least intelligent of the Glass children and was therefore always being kept off school to help in the house. The excuse offered by Senga’s mother, Dinah, was, “Well, don’t I have to go out working? Not to mention entertaining the troops?”

Since moving into Restalrig Circus two years ago, the five Glass children and their mother had built up a close friendship with Etta and her husband, who lived just over the road, on the posh side of Learig Close. Etta’s husband, Harry, had also been called up and was now based with the RAF at Pitreavie over in Fife, leaving his childless wife to look after his aged father, Jacob. The old man and his wife had adopted Harry as a baby and, after Jacob’s wife had died fifteen years back, it had proved quite hard for the widower to cope with the somewhat wayward teenager that his adopted son had become. So Jacob was greatly relieved when, some twelve years ago, Harry had courted and then married Etta, a naïve young country lass. The Glass family now knew Etta to be one of those gentle children of nature who had never a bad word to say about anyone, yet was essentially unable to cope with many of the harsher realities of working-class life. Etta had proved to be a real blessing to the Glass family since she simply assumed it was her duty to come in at all times to look after Phyllis. Not that Etta ever did any

hard

housework – after all, she didn’t do it in her own house so why should anyone expect her to do it elsewhere? More importantly, what she did do, most successfully, was keep the children company and tell them innumerable stories while chain-smoking any kind of cigarette she could lay her hands on.

“Now, I’ve fed Phyllis her porridge, Etta,” Senga quickly announced, as she began to pull on a pair of Wellingtons. “And if you could just stay here till I get back – I won’t be long.”

“You won’t?” said Etta, half-regretfully: she didn’t care

how

long Senga was going to be.

“Naw. I’ve just to get our alarm clock out of the pawn …”

“Getting something

else

out of the pawn?”

Senga flinched as she went over to the coal scuttle and dragged out a canvas bag which clinked loudly as she swung it up on to the tabletop. “See when I went and got the blankets out last week I didnae half get a right red face when Mr Cohen bawled out that he disnae like getting his money,” Senga looked around to make sure she was not being overheard before whispering, “in penny dribs an drabs!”

“Aye,” countered Etta, “things haven’t half looked up since your Mammy got yon job on the buses.”

“That’s right. And d’you know this, Etta? When she’s no had time to collect aw the folks’ fares and gie them their tickets, she just stands at the door and clicks the machine as they get aff the bus while they’re dropping the pennies intae her hand,” confided Senga. “What else can she do but bring the money hame? She doesnae want to lose her job for no doing it right, does she?” Etta made no comment but lit up a cigarette, so Senga felt she had to justify her mother’s actions and hurriedly continued, “Besides, between the bus fares and Daddy never seeming to get laid off work for a day or two now he’s in the army – which means we get his full pay every week …”

“Senga! It’s not pay. It’s an army marriage allowance,” Phyllis emphasised as she corrected her sister, who she considered was always needing help to get things right. “And do you know,” she continued, turning to face Etta, “our Daddy even told them to send on another nine shillings from his allowance to us every week?” Phyllis sighed and wiped a tear from her eye. “And that means he’s probably not left himsel’ enough to buy a packet of fags.”

Etta drew on her cigarette again before looking disdainfully at the broken stub. “Well, if he’s like me and can only get his hands on these awful Turkish Pasha fags he’s better off without them.” She now pulled some tobacco from her mouth before flinging the dog-end in the fire.

“Anyway, it doesn’t matter if it’s called pay or allowance,” Senga protested. “Daddy’s money comes in every week, so things are getting better.”

“And Etta, ken something else? Senga’s to get a

whole

half pound of Spam and a big tin of Heinz beans from the store for our tea.” Phyllis as usual felt she had to butt in to help Senga, yet couldn’t resist licking her lips before adding, “And she’s also to get a whole bob’s worth of chips from the Chippie to go with them!”

“A

whole

twelve pennyworth?” teased Etta.

Senga nodded. “But forbye the Pawn, the Store an’ the Chippie, I’ve got to go and see Granny Kelly to tell her not to wait for Mammy on Friday night as she’ll not be going to chapel.”

“No got anything to confess?” asked Etta, who knew that Friday night was Confession Night. Senga’s head dipped briefly in agreement. “Right! Off ye go.”

Etta then turned towards Phyllis. “And now, ma wee dollie-dumplin’, how does a wee bit hot toast smothered in best butter sound to you? And all washed down with some nice sweet tea, of course.”

Senga didn’t have a pixie hood but she did possess a scarf that Granny Kelly had folded in two and sewn up part-way to look as if she had. Then, bending her covered head into the driving blizzard, she muttered, “Blast this snaw!” as she hirpled her way along Restalrig Circus towards Hooper’s Aw-thing Shop – which did literally seem to sell anything and everything. There were even rolls of salt fish inside the lower edges of the window and in summer these always proved a happy hunting-ground for swarms of bluebottles. And as for old Mr Hooper’s apron, that was indeed an advert for

Before Persil

. On that account Senga was not allowed to buy from Hooper’s very often. Yet Hooper’s three granddaughters (for whom he’d taken responsibility when his distraught daughter arrived home after having been deserted by her ne’er-do-well husband) all attended the Mary Erskine Merchant Company school, where every pupil had to wear uniform – straw hats and gingham dresses in the summer; and, in winter, nap coats and long black stockings, held up by proper suspender belts and not tight, itchy elastic bands.

By now Senga was going past Hooper’s and was about to walk down Restalrig Road when she luckily turned the corner just in time to see the small No.13 bus that ran between Ravelston in the west of the city to Bernard Street in Leith. Surely, she thought, with the weather being so bad and her having to keep from getting her bad leg broken, not to mention (the most important issue) being seen by a lurking attendance officer, wasting a penny on a bus journey must surely be permitted!

As she began to hobble quickly towards the bus stop, Senga gestured wildly to the driver, only to discover that it was an old friend, Joe Armstrong, who now had taken both hands off the steering wheel and was gaily waving to Senga. Though the bus seemed totally out of control by this point as it hurtled towards her, Senga knew well that it was only another silly prank on Joe’s part, and as the bus shuddered to a halt she simply giggled. It was just like Joe to clown in that fashion. He and Senga’s mother had at one time been in service together on a wealthy estate, Joe being chauffeur and Dinah the table maid. The Abbey family for whom they worked had always insisted that Joe pick up Dinah at the railway station in Melrose when she returned from her day off. And so the two became and remained very good friends. Indeed it was widely believed that Joe fancied Dinah – but that was only to be expected, since every man in the neighbourhood was attracted to her. Dinah, however, belonged to a devout Catholic family who had sent the young woman away into service solely to keep her away from Tam Glass, her Protestant boyfriend – all to no avail because, despite the objections from both families, Dinah and Tam married and (in Senga’s opinion, together with that of all of her siblings) had lived happily ever after.