CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (10 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

By using selectors based on the document's language, authors can create CSS rules

that apply to a large number of similar elements just as easily as they can construct

rules that apply in very narrow circumstances. The ability to group together both

selectors and rules keeps style sheets compact and flexible, which incidentally leads to

smaller file sizes and faster download times.

Selectors are the one thing that user agents usually must get right because the

inability to correctly interpret selectors pretty much prevents a user agent from using

CSS at all. On the flip side, it's crucial for authors to correctly write selectors

because errors can prevent the user agent from applying the styles as intended. An

integral part of correctly understanding selectors and how they can be combined is a

strong grasp of how selectors relate to document structure and how mechanisms—such as

inheritance and the cascade itself—come into play when determining how an element will

be styled. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Chapter 2

shows how document structure and CSS

selectors allow you to apply a wide variety of styles to elements. Knowing that every valid

document generates a structural tree, you can create selectors that target elements based

on their ancestors, attributes, sibling elements, and more. The structural tree is what

allows selectors to function and is also central to a similarly crucial aspect of CSS:

inheritance.

Inheritance

is the mechanism by which some property values are passed

on from an element to its descendants. When determining which values should apply to an

element, a user agent must consider not only inheritance but also the specificity

of the declarations, as well as the origin

of the declarations themselves. This process of consideration is what's known as the

cascade

. We will explore the interrelation between these three

mechanisms—specificity, inheritance, and the cascade—in this chapter.

Above all, regardless of how abstract things may seem, keep going! Your perseverance

will be rewarded.

You know

from

Chapter 2

that you can select elements using a

wide variety of means. In fact, it's possible that the same element could be selected by

two or more rules, each with its own selector. Let's consider the following three pairs

of rules. Assume that each pair will match the same element:

h1 {color: red;}

body h1 {color: green;}

h2.grape {color: purple;}

h2 {color: silver;}

html > body table tr[id="totals"] td ul > li {color: maroon;}

li#answer {color: navy;}

Obviously, only one of the two rules in each pair can win out, since the matched

elements can be only one color or the other. How do you know which one will win?

The answer is found in the

specificity

of each selector. For

every rule, the user agent evaluates the specificity of

the selector

and attaches it to each declaration in the rule. When an element has two or more

conflicting property declarations, the one with the highest specificity will win out.

This isn't the whole story in terms of conflict resolution. In fact, all style

conflict resolution is handled by the cascade, which has its own section later in

this chapter.

A selector's specificity is determined by the components of the selector itself. A

specificity value is expressed in four parts, like this:0,0,0,0. The actual specificity of a selector is determined as follows:

For every ID attribute value given in the selector, add

0,1,0,0.For every class attribute value, attribute selection, or pseudo-class given in

the selection, add0,0,1,0.For every element and pseudo-element given in the selector, add

0,0,0,1. CSS2 contradicted itself as to whether

pseudo-elements had any specificity at all, but CSS2.1 makes it clear that they

do, and this is where they belong.Combinators and the universal selector do not contribute anything to the

specificity (more on these values later).

For example, the following rules' selectors result in the indicated specificities:

h1 {color: red;} /* specificity = 0,0,0,1 */

p em {color: purple;} /* specificity = 0,0,0,2 */

.grape {color: purple;} /* specificity = 0,0,1,0 */

*.bright {color: yellow;} /* specificity = 0,0,1,0 */

p.bright em.dark {color: maroon;} /* specificity = 0,0,2,2 */

#id216 {color: blue;} /* specificity = 0,1,0,0 */

div#sidebar *[href] {color: silver;} /* specificity = 0,1,1,1 */

Given a case where anemelement is matched by

both the second and fifth rules in the example above, that element will be maroon

because the fifth rule's specificity outweighs the second's.

As an exercise, let's return to the pairs of rules from earlier in the section and

fill in the specificities:

h1 {color: red;} /* 0,0,0,1 */

body h1 {color: green;} /* 0,0,0,2 (winner)*/

h2.grape {color: purple;} /* 0,0,1,1 (winner) */

h2 {color: silver;} /* 0,0,0,1 */

html > body table tr[id="totals"] td ul > li {color: maroon;} /* 0,0,1,7 */

li#answer {color: navy;} /* 0,1,0,1 (winner) */

You've indicated the winning rule in each pair; in each case, it's because the

specificity is higher. Notice how they're sorted. In the second pair, the selectorh2.grapewins because it has an extra1:0,0,1,1beats out0,0,0,1. In the third pair, the second rule wins

because0,1,0,1wins out over0,0,1,7. In fact, the specificity value0,0,1,0will win out over the value0,0,0,13.

This happens because the values are sorted from left to right. A specificity of1,0,0,0will win out over any specificity that

begins with a0, no matter what the rest of the

numbers might be. So0,1,0,1wins over0,0,1,7because the1in

the first value's second position beats out the second0in the second value.

Once the specificity of a selector has been

determined, the value will be conferred on all of its associated declarations.

Consider this rule:

h1 {color: silver; background: black;}

For specificity purposes, the user agent must treat the rule as if it were

"ungrouped" into separate rules. Thus, the previous example would become:

h1 {color: silver;}

h1 {background: black;}

Both have a specificity of0,0,0,1, and that's

the value conferred on each declaration. The same splitting-up process happens with a

grouped selector as well. Given the rule:

h1, h2.section {color: silver; background: black;}

the user agent treats it as follows:

h1 {color: silver;} /* 0,0,0,1 */

h1 {background: black;} /* 0,0,0,1 */

h2.section {color: silver;} /* 0,0,1,1 */

h2.section {background: black;} /* 0,0,1,1 */

This becomes important in situations where multiple rules match the same element

and where some declarations clash. For example, consider these rules:

h1 + p {color: black; font-style: italic;} /* 0,0,0,2 */

p {color: gray; background: white; font-style: normal;} /* 0,0,0,1 */

*.aside {color: black; background: silver;} /* 0,0,1,0 */

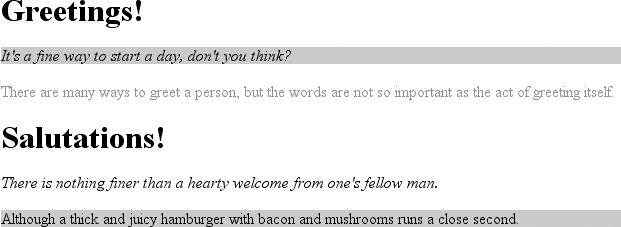

When applied to the following markup, the content will be rendered as shown in

Figure 3-1

:

Greetings!

It's a fine way to start a day, don't you think?

There are many ways to greet a person, but the words are not as important as the act

of greeting itself.

Salutations!

There is nothing finer than a hearty welcome from one's fellow man.

Although a thick and juicy hamburger with bacon and mushrooms runs a close second.

Figure 3-1. How different rules affect a document

In every case, the user agent determines which rules match an element, calculates

all of the associated declarations and their specificities, determines which ones win

out, and then applies the winners to the element to get the styled result. These

machinations must be performed on every element, selector, and declaration.

Fortunately, the user agent does it all automatically. This behavior is an important

component of the cascade, which we will discuss later in this chapter.

As mentioned earlier, the universal selector does not contribute to the

specificity of a selector. In other words, it has a specificity of0,0,0,0, which is different than having no specificity

(as we'll discuss in "

Inheritance

").

Therefore, given the following two rules, a paragraph descended from adivwill be black, but all other elements will be gray:

div p {color: black;} /* 0,0,0,2 */

* {color: gray;} /* 0,0,0,0 */

As you might expect, this means that the specificity of a selector that contains a

universal selector along with other selectors is not changed by the presence of the

universal selector. The following two selectors have exactly the same specificity:

div p /* 0,0,0,2 */

body * strong /* 0,0,0,2 */

Combinators, by comparison, have no specificity at all—not even zero specificity.

Thus, they have no impact on a selector's overall specificity.

It's important to note the difference in specificity between an ID selector and an

attribute selector that targets anidattribute.

Returning to the third pair of rules in the example code, we find:

html > body table tr[id="totals"] td ul > li {color: maroon;} /* 0,0,1,7 */

li#answer {color: navy;} /* 0,1,0,1 (winner) */

The ID selector (#answer) in the second rule

contributes0,1,0,0to the overall specificity

of

the selector. In the first rule, however, the attribute

selector ([id="totals"]) contributes0,0,1,0to the overall specificity. Thus, given the

following rules, the element with anidofmeadowwill be green:

#meadow {color: green;} /* 0,1,0,0 */

*[id="meadow"] {color: red;} /* 0,0,1,0 */

So far, we've seen specificities that begin with a

zero, so you may be wondering why it's there at all. As it happens, that first zero

is reserved for inline style declarations, which trump any other declaration's

specificity. Consider the following rule and markup fragment:

h1 {color: red;}

The Meadow Party

Given that the rule is applied to theh1element, you would still probably expect the text of theh1to be green. This is what happens in CSS2.1, and it happens because

every inline declaration has a specificity of1,0,0,0.

This means that even elements withidattributes that match a rule will obey the inline style declaration. Let's modify the

previous example to include anid:

h1#meadow {color: red;}

The Meadow Party

Thanks to the inline declaration's specificity, the text of theh1element will still be green.

The primacy of inline style declarations

is new to CSS2.1, and it exists to capture

the state of web browser behavior at the time CSS2.1 was written. In CSS2, the

specificity of an inline style declaration was1,0,0(CSS2 specificities had three values, not four). In other words,

it had the same specificity as an ID selector, which would have easily overridden

inline styles.

Sometimes, a declaration is so important that it outweighs all other

considerations. CSS2.1 calls these

important declarations

(for

obvious reasons) and lets you mark them by inserting!importantjust before the terminating semicolon in a declaration:

p.dark {color: #333 !important; background: white;}

Here, the color value of#333is marked!important, whereas the background value ofwhiteis not. If you wish to mark both

declarations as important, each declaration will need its own!important marker:

p.dark {color: #333 !important; background: white !important;}

You must place!importantcorrectly, or the

declaration may be invalidated.!importantalways

goes at the end of the declaration, just before the

semicolon. This placement is especially important—no pun intended—when it comes to

properties that allow values containing multiple keywords, such asfont:

p.light {color: yellow; font: smaller Times, serif !important;}

If!importantwere placed anywhere else in thefontdeclaration, the entire declaration would

likely be invalidated and none of its styles applied.

Declarations that are marked!importantdo not

have a special specificity value, but are instead considered separately from

nonimportant declarations. In effect, all!importantdeclarations are grouped together, and specificity conflicts

are resolved relative to each other. Similarly, all nonimportant declarations are

considered together, with property conflicts resolved using specificity. In any case

where an important and a nonimportant declaration conflict, the important declaration

always

wins.

Figure 3-2

illustrates the result of the

following rules and markup fragment:

h1 {font-style: italic; color: gray !important;}

.title {color: black; background: silver;}

* {background: black !important;}

NightWing

Figure 3-2. Important rules always win

Important declarations and their handling are discussed in more detail in

"

The Cascade

" later in this

chapter.