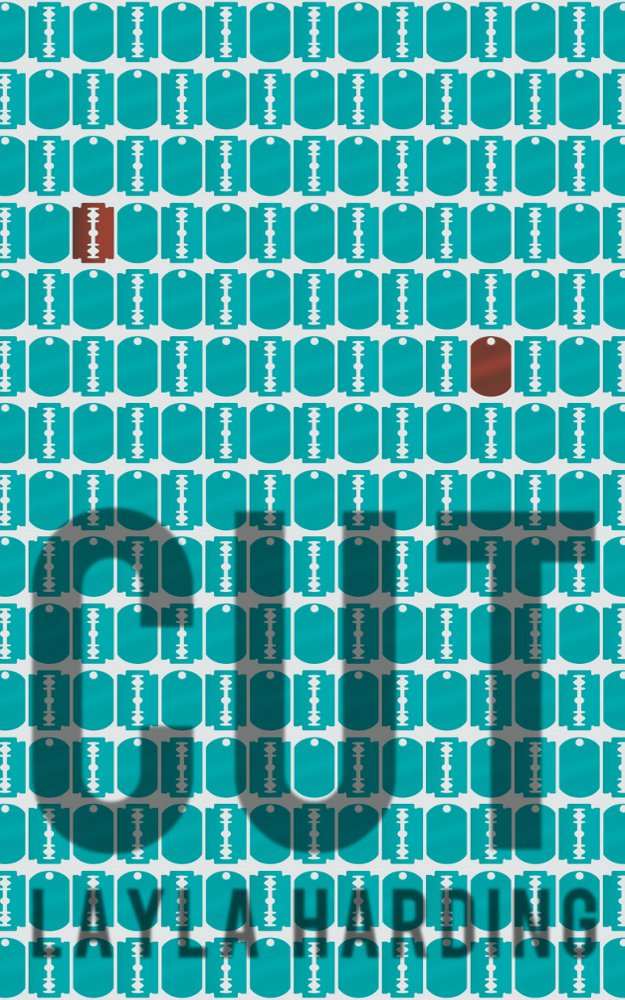

Cut

Authors: Layla Harding

Layla Harding

Her father is a nightmare.

Her mother is a drunk.

Persephone is a practicing suicide.

She's been at home with danger all her life, and now - one way or another - it's time for her to leave.

First published 2015 by Starshy

The stories in this book are all works of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2015 by Layla Harding.

All rights reserved.

Book and jacket design by Evangeline Jennings

C U T

1.

I started practicing suicide when I was twelve years old. That’s kind of funny. It makes it sound like some sort of religion I picked up. She’s

a non-practicing Catholic… I’m a practicing suicide.

I guess it was a religion in a way, with its own rituals and services. I was a devout follower.

I always locked my bedroom door. I don’t know why. My mother never came to my room, and if my father wanted in, a lock wouldn’t stop him. It never did.

Then I chose my music. Something soothing but not too poignant—certainly nothing controversial. It always infuriated me when some kid blew his brains out with Marilyn Manson streaming through Pandora and all of a sudden it’s the musician’s fault. Marilyn and Ozzy weren’t the problem. The demon lurking in the dark didn’t bite the heads off live bats or parade around in make-up. He didn’t sing. He whispered.

The razors were kept tucked away in the back of a dresser drawer. You know the kind you can buy in a pack of ten for a buck? The kind that will shred your legs if you actually try to shave with them? Other razors would work, but they were damn near impossible to get apart.

Usually I had the plastic casing snapped before the first song was over. I always took such care in the process so I didn’t cut my fingers. Don’t ask me why—it’s like the death row doctor sterilizing the needle for the lethal injection. Another part of the ritual.

The thin blade would glimmer under the lamp next to my bed and sing out the siren song of the depressed. “Use me, trust me. I can make it all better.”

I always started with the right arm. I heard in some movie cutting vertically, along the veins, instead of side to side would do more damage. Go up the river, never across. Should someone discover me before I bled out those wounds would be harder to stitch. A Good Samaritan at the ER would have a tough time saving me from me.

After pumping my fist a few times to draw the vein to the surface, I traced its blue line down my arm with the blade. Methodically charting the course before I began my journey. Sometimes my hand shook too much to get it right the first time, so I needed the map.

The first cut followed the path I marked, quick and deep. I was fascinated to see my wrist open up. The layers of skin looked thin and pale like fresh sliced mozzarella. There was a split second when the wound stayed bleach-white as if my body was deciding whether or not it wanted to bleed.

Then there was the big vein itself. It dodged and rolled from side to side, barely avoiding the blade. What would have happened if I ever had severed it? I imagined a geyser of blood spewing out like a scene in a Tarantino movie. It would splash against the furniture and walls, coating everything in a slick, sticky layer of red. When they discovered my lifeless body the next morning, everything would have a warm glow from the sun streaming through the stained glass windows. A cathedral of my own making.

My mother would scream so hard a muscle would rip in her throat, cutting off the shriek prematurely and making her sound like a choking frog. My father would throw up a thin line of brown fluid (the first cup of coffee he drank while reading the paper, wondering why I wasn’t out of bed yet). They would try to steady themselves against the walls, realizing too late they were covering themselves with the slick coating of blood on the drywall.

Then the smell would hit them—the rusty, decaying smell of their daughter’s body. The entire scene would drive them beyond insanity. Days later, when neither of them had been seen outside of the house, and I had not been in school, the cops would arrive. Poor officers—they wouldn’t know what to do with the catatonic couple they found in the basement or the dead girl in the back room. How would they radio it in? This was the part of me that watched too many horror movies.

The other part of me—the part that believed someone still cared—envisioned a scene where my blue-lipped, pale body lay peacefully on the bed. Too weak to save myself I would be Snow White on a crimson bed, my black hair throwing the porcelain of my skin into sharp contrast. I would close my eyes and let go.

In this scene, the discovery was anguished and full of self-blame. How could they not have seen what they were doing to their own daughter? They would yell and berate each other. They would gather my corpse into their arms, hugging and kissing me. They’d beg God to give me back, promising to never make those mistakes again, if He would only give their baby back.

My spirit would watch from above, sad they could not say they were sorry while I was alive but grateful a lesson had been learned. I would reach down and let them know I forgave them. In my own ghostly way, I would tell them to go forth and sin no more. And then I would be free from this world.

But I never could catch the vein. Let’s face it—I didn’t try too hard. I sat there and watched the blood pool and drip down my arm until it began to slow and clot.

By that time the service was almost over, the final hymn about to be sung. I would pull out the box of bandages from under my bed. It would be long sleeves for me the next few weeks, even in the summer.

At some point it stopped being about suicide, although it was always the goal. The journey, the pain and sacrificing of flesh, began to mean more. The rituals are addictive, like the chills from the first tent revival. People spend their entire lives trying to recapture this simple faith—trying to find the ultimate mountaintop peace. I found a way to wash away my sins with my own blood, but I couldn’t find the courage to make it last.

During my senior year I counted a hundred and seventeen scars on my body. They were under my breasts, the inside of my thighs, my hips, lower stomach, and crooks of my elbows. On the nights I needed to control the pain, have a blood rite, I would leave my wrists alone and attack a different part of my body.

What else could I do when the demon lurking in the dark whispered, “Don’t worry, honey. It’s Daddy,” and the only person who wanted to save me was me?

Towards the end of my senior year, I realized it was time to either close the deal or knock off my nasty little habit of slicing myself open. The euphoria still came when I felt the sting of metal on my skin, but I was doing it too often. I looked like a human cutting board, scarred and scored from overuse.

I came to this conclusion the morning after a particularly brutal session. As usual I struggled to figure out what to wear. Mom said it was supposed to be hot. Without missing a beat, I explained with the new air conditioning system in the school, it got downright cold in there.

I liked keeping track of the lies I told during the day. I put them in little columns in my head: lies I told that people believed; lies people believed because it made their lives easier; and lies no one in their right mind should ever believe but they didn’t care enough to call me out on. I never needed a column for lies people called BS on.

One of the cuts from the night before opened up while I was pulling my hair back. I had sliced deeper than I’d thought. If I’d had more courage I wouldn’t have been getting ready at all.

The mountaintop feeling was quickly replaced by guilt. When the blood started rolling down my arm I felt dirty. I wanted to get back in the shower and scrub my body raw. I never felt nastier than the day after cutting. The line of blood was a billboard advertising my failure. I couldn’t end it, but I couldn’t stop trying. I never did drugs (not even a joint), but I could imagine what the crash felt like. It sucked.

On the way to school I smoked like a fiend. Some people (hateful, rotten people who couldn’t mind their own business) told me I was slowly killing myself with this disgusting habit. That was the whole point. Idiots. I hated when people felt the need to comment on things they knew nothing about.

Pulling my backpack from the car, I banged my wrist. I waited a few minutes to make sure it wasn’t going to open up.

This is going to be a long damn day.

And I was right. It was filled with the mundane minutiae of normality. Meaningless conversations in the hallways, teachers intent on shaping young minds into their agendas, and an inedible lunch. I told my English teacher my hard drive crashed and promised to turn in my homework the next day. The paper was actually safely tucked away in my bag—I just wanted to see if she would let me get away with it. She did. I told the girl sitting next to me in Calculus her Lucky jeans so did not make her butt look fat—if anything they made it look smaller. I didn’t say I meant compared to a rhino’s ass. And I told the football player who asked me out he was way too good for me and going out with him would only make me nervous. The only thing that made me nervous was the thought of an entire night watching him struggle to carry on a coherent conversation that didn’t involve first downs. It was amazing the shit people would buy to preserve their sense of balance in the world.

The only abnormal part of my day was the constant vibration of my cell phone. There were four calls from a number I didn’t recognize. On the last one whoever it was finally left a voicemail. I was mildly curious to see who they thought they were calling but had to wait until the end of school to check. The penalties for on-campus cell phone use were harsh.

Because I sat on the fringe of the popular crowd, I could go unnoticed for days if I kept my head down. My family was upper-middle class and that was the best way to describe my social status. I knew about all the parties, but no one would ever miss me if I wasn’t there. I would never be on the Homecoming court, but I would always have a date to the dance. When I wanted friends, I could find them. When I didn’t, no one came looking for me. I rarely wanted friends.

I think I was only ever included out of a vague sense of guilt and a high schooler’s need to keep the world making sense. I came from a semi-wealthy family. I was pretty (not traffic-stopping or anything, but pretty). I was in the top ten of my class. I was supposed to want to belong. I was supposed to want to be a part of ‘them’. As long as they felt I was still there somewhere, close by, all was right with the world. The cliques were in place, the social structure unshaken, and rose-colored glasses remained firmly attached to faces.

After my last class, I raced through the halls and out to my car. Two blocks from school, I could light a much needed cigarette. It cracked me up. The security officer could smell a smoke you had two days ago and bust you for it. On the other hand, he couldn’t seem to catch the kids popping Oxy and Vicodin in the bathrooms at lunch. All a matter of priorities I guess.

I had barely taken the first drag when my phone lit up again.

“Hello?”

“Um yes. I was tryin’ to reach Ken Austin.”

“Wrong number.”

“Are you sure?”

“I think I know my own number.”

“Sorry to trouble you, miss.”

I deleted the voicemail without listening to it.

Later that night I sat in my room staring at my Calculus book, listening to my parents’ footsteps above me. Mom’s slowed as the night progressed (it was hard to walk after a gallon of gin and tonics). Dad’s sped up as he paced from his office to the bathroom to the kitchen.

He didn’t like being at home and walked around the house with the frustration of a caged hyena. I knew why he preferred being on the road, but I wasn’t sure who she was. It was either the chick from Human Resources who somehow ended up on a lot of his sales trips or his assistant. They both had the look of professional gold diggers, and either way, he got cranky when he was home for too long.

When it seemed his pacing had finally ceased (where he ended up was anyone’s guess—God knows it wasn’t in Mom’s room. They hadn’t shared a bed since I was a little girl), I gave up on the pages of equations in front of me. I had been staring at the same problem for almost thirty minutes, and it still wasn’t any clearer than when I began.

My piano called from the room across the hall. A few songs and I would get back to work. Music’s supposed to be good for your brain, right? Aren’t you supposed to listen to classical music when doing math? Could I rationalize abandoning my homework? Of course I could.

Sitting down in front of the keys, I felt my shoulders relax and the knots start to loosen in my back. Music was my one pure escape. It had never been touched or tainted by anything bad. Well, there was that one time, right after my first little brush with a razor blade. My piano teacher noticed the cuts and asked me what had happened. I made up some lame excuse about losing a fight with my cat—I didn’t own a cat. It was also my first experience with lies people believe to make their lives easier. It was shocking and invigorating.